Bombay to Beijing by Bicycle (19 page)

Read Bombay to Beijing by Bicycle Online

Authors: Russell McGilton

July

The mist wet our eyelashes and made us look like clowns. We had climbed the 30 kilometre road through the vast, changing landscape of lush green hills towards the barren terrain of the Rohtang Pass (3978 metres).

Despite leaving half our luggage in Manali it was still a tough ride. The road was muddy, narrow and slippery. Sporadic streams of

four-wheel

drives, tourist buses and trucks passed us, leaving us to cling on to what space was left of the road.

I was in a foul mood. To my wounded pride

xx

, Rebecca was way ahead of me, effortlessly going up and up and up like a motorbike, disappearing in and out of the clouds. She waited for me by a stream, not showing any fatigue whatsoever.

‘Oh, this is

sooooo

beautiful, Russ! It’s so great to be able to sit here and take in the view.’

‘Yeah, right!’

‘How much further?

‘Another five ks.’

‘Oh!’ she said brightly, ‘is that all?’

And off she went, helium it seemed, in her tyres. I grunted and followed after her, up another switchback, past a stream until we finally reached the settlement of Marhi – a weary collection of tented blue tarp restaurants bubbling big pots of

dahl

, chick peas and rice.

We were heading up to the town of Leh in the Kingdom of Ladakh, the north-eastern region of Jammu-Kashmir, a distance of 473 kilometres from Manali.

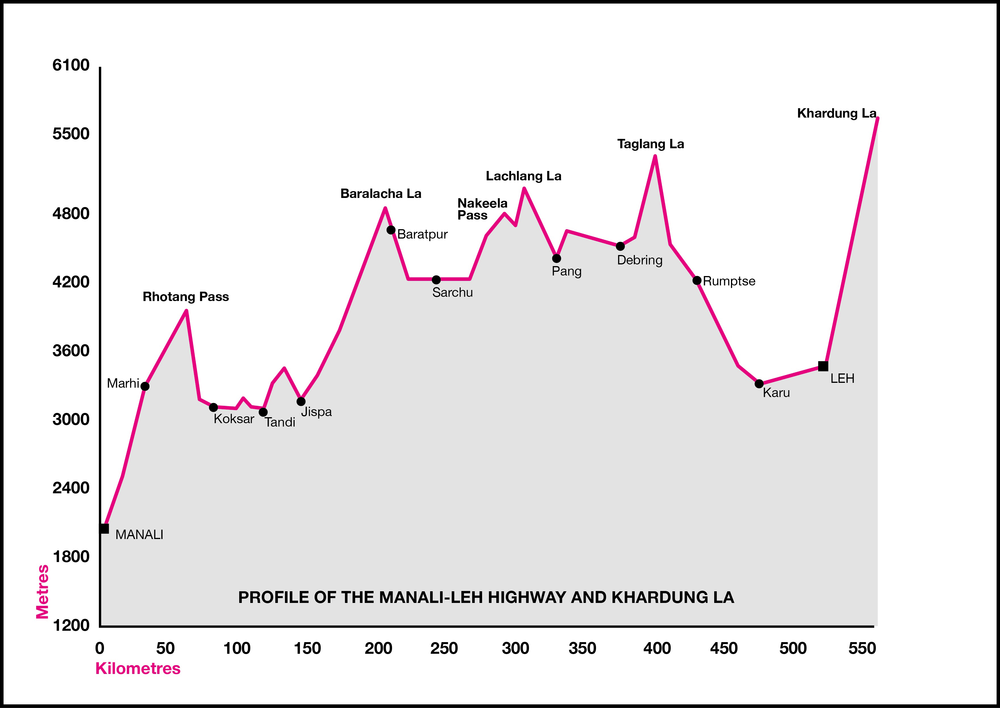

Set in a high-altitude desert between the Karakoram and Himalayan ranges, Leh is only accessible during the warmer months of the year; the pass was, well, impassable in heavy snow. The highway to the town was one of the highest in the world (5328 metres) and offered spectacular scenery: from the lush green hills out of Manali to the jagged, snow-capped mountain ranges as the road headed through a lunar landscape, a vast plateau towards Tibet. It was here that a variety of Tibetan sub-groups had lived in virtual isolation from Chinese and Indian influence.

However, enticing as all of this was, it was dangerous. Only a week ago, an Austrian cyclist had died on a 2500 metre pass. There were also frequent rockslides.

Bec and I were still together … for now. We would continue as a couple until we went in our different directions: Bec, low on funds, would go to Taiwan to teach English, while I would start a Vipassana Meditation course at a retreat near Dharamasala.

Our biggest obstacle of this trip was that we didn’t have a tent, as I’d ditched the other one after The Night of the Slow Drips. The other issue was that distances between towns were at least 70 kilometres and, with an average of 5 kilometres an hour uphill, it was more than likely to take us most of the day just to squeeze 30 ks out. Then, of course, there was the issue of scarcity of water. To address these issues we bought a big tarp to put over the bikes to act as a tent and bought extra bottles, filling up in towns as much as we could.

Now in Marhi we ordered up big – veggie soup,

dahl

, fried rice,

gobi mutter

and coffee. The

dahl

was hearty, warm and just the thing we needed after a cold ride as we contemplated a wet cold night under our tarp. An Israeli with hair like spider legs and quite cheekily cooking up his own meal in the restaurant with his friends, told us of a bunked room – the waiters’ quarters – that was available.

We took it despite the state it was in – chopped brown cabbage in the corner, cigarette butts on the floor, assorted clothes and blankets strewn on beds. We hitched up on the top bunk together, Bec spreading her sarong over a wire cord across our bunk for privacy. Later, that night, needing a pee, I had to step over the waiters as they puffed and snored before eventually climbing out of a window and through muddy puddles in bare feet. As I relieved myself, I watched the fog settle over the black rocks and around the camp. It was eerily quiet and yet somehow wonderfully magical.

In the morning, an overly exuberant Frenchman jumped around us taking photographs of our bikes, his camouflage pants whooshing around us like falling trees.

‘Wow! Zis is amazing! You really cycling up here? Man!’

He was part of a French documentary team on a quest to find the burial site of Jesus Christ.

‘Er … aren’t you a little off … target?’

‘No, he died here in India. In Kashmir.’ Jesus, he believed, had come to India and learnt yogic breathing from a master that helped him survive his crucifixion.

‘There was no resurrection. He was always alive. We will find his grave!’

He jumped into the back of the Jeep and was gone.

We started slowly in the falling rain, and fortunately, by the time we get to the Rohtang Pass, the rain had cleared. In Tibetan it is called the

Rohtang La

and its literal meaning is ‘pile of corpses’ due to the high number of people who have perished trying to cross in it in bad weather.

Today it was living up to its reputation: a cold and bitter wind shrieked up the valley bringing flakes of snow like dandruff and adding to our altitude headaches. This didn’t seem to put off

day-trippers

who were wrapped in rented yak skins like strange black wraiths while their photos were taken by relatives. Behind them tourist buses tore through the mud as they returned to Manali.

We zoomed down a 15km descent to Khoksar and spent the night with the smell of unwashed potatoes that were piled to the ceiling in the next room.

***

Before us, a clear blue sky stretched across from the snow-capped mountains down to a tumbling, rugged lunaresque landscape. It was a glorious day and we were literally jumping out of seats with the sheer joy of being in it.

To celebrate, Bec had a novel suggestion.

‘Get your gear off!’

I threw the bike off the road and behind the rocks, I stripped off. Bec stood ready with the camera and took pictures as I posed à la Priscilla Queen of the Desert, my sarong billowing behind me.

‘Now me!’ In a second Bec was also naked, her smooth white curves an erotic contrast to the sharp, jutting, rocks behind her. She danced among the waves of shimmering heat, skipping from rock to rock, arms flailing around, singing ‘I’M NAKED! NAA-AKED!’

Putting the camera on self-timer, we posed together and waited for it to go off (the camera, I mean!). Just as the camera clicked, a truckload of Indian road-builders sailed past, then groaned to a halt, then began to reverse. We scampered for our clothes, struggling to get them on quickly – arms through this sleeve and that, shorts on backwards, one shoe on – before jumping on our bikes, skipping and slipping on the pedals.

The truck snorted a dark cloud of disappointment and drove onwards, eventually eaten up by a massive rock as it turned.

With a slight gradient in our favour, our tyres hummed on a straight road to Sarchu, one of the numerous tented cities that existed only during the warmer months. We could not enjoy this any other way but on bicycle, the air and the landscape washing through us, an electric feeling of being alive.

In Sarchu (another collection of battered tents) we met two English lads, Harry and Keith, who had just rolled up on new 500cc Royal Enfield Bullet motorbikes. These were British motorbikes dating back to 1949 and their popularity in India had been signalled by the need to patrol their new neighbour, Pakistan. By 1955 a factory had been set up in Madras and, when the parent company ceased production, India Enfield continued to make them based on the old designs.

Harry had had a collision with a truck, smashing his headlight. While he and Keith went about fixing the damage, an Indian man with a keenness for motorbikes stood behind them, watching their every move.

‘I have an Enfield too,’ he said to Harry before succumbing to what appeared to be either a terrible sinus condition aggravated by the dust or Tourette’s.

‘I rented one years ago from Manali up to the Rohtang Pass – SNORT! SNIFF! GRUNT! WOOF! – it was a wonderful feeling – SNIFF! GRUNT! – I fell in love with it instantly – WOOF!’

‘Uh huh,’ Harry said, attempting to unscrew the headlight casing.

‘I could get it up to 50 miles per hour.’

‘Right.’ The screwdriver slipped out of Harry’s hand.

‘SNIFF! WOOF!’

Helmut, an Austrian cyclist in his 50s, was sharing a tent with the British lads. He was dressed in tights and a cycling shirt, and danced about the campsite like Peter Pan.

‘Ja, I came up from Srinagar to Leh. So many trucks! Army everywhere. I go upstairs 500 metres first day,’ he said, taking out a small notebook. ‘No, 550. My altimeter says I climb 1250 metres,’ he said proudly. He was carrying 35 kilograms on a touring bike (bigger wheels and heavier than a mountain bike) and dozens of water bottles fitted to the frame. ‘Ja! Because I

neeeeeeed

it!’

The next day, we passed a sign: ‘21 loops’, indicating the number of switchbacks.

‘Oh, dear God!’ Rebecca complained.

‘We’ll take plenty of breaks. Don’t worry.’

The only thing that lightened our mood was another one of those bizarre Indian traffic signs:

I laughed so much I nearly crashed into it!

‘Hey, Bec. I bet TATA truck drivers must be thinking about that as they go hurtling over a cliff: “OH, SHIT! I’M GOING TO GET A TICKET!”’

But nothing, it seemed, could lift her out of her exhaustion.

But it wasn’t the climbing that was the most difficult part. Apart from having to dodge convoys of trucks and falling rocks, it was the heat that exhausted us faster than anything else. It fried everything – even the road.

As I rested my bike against a cutting I noticed it shrinking before my eyes. It was sinking in a pool of tar. I quickly pulled it out. Up ahead, the road sweated; it was literally melting before us. We got back on our bikes and continued cycling, struggling with the soft tar, our tyres sounding as if they were rolling over Velcro, the road clutching at them, fighting for them to stop.