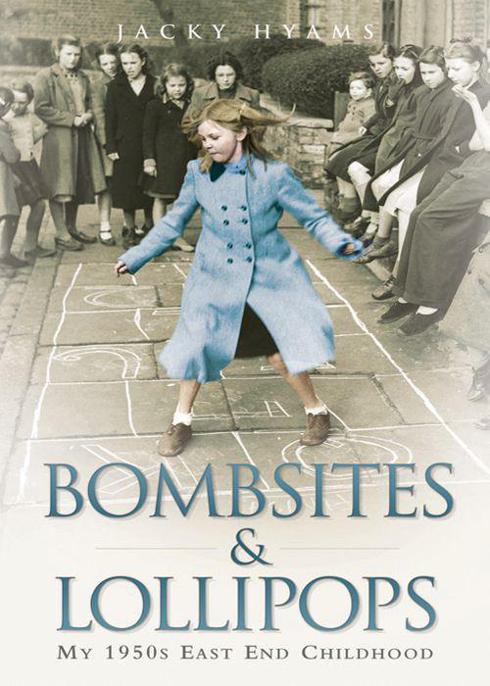

Bombsites and Lollipops: My 1950s East End Childhood

Read Bombsites and Lollipops: My 1950s East End Childhood Online

Authors: Jacky Hyams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #Social Science, #London (England), #Travel, #General, #Customs & Traditions, #Great Britain, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History

OREWORD

All gratitude to Wensley Clarkson for encouraging me to venture into my past in the first place and helping me understand that the journey may be daunting – but is well worth taking.

Most sincere thanks to Tammy Cohen, for her friendship and valuable support and to my dear and lifelong friend Larraine De Napoli, who was generous with her time and patience in sharing her recollections of our teenage years.

Thanks too to John Parrish in Sydney, who never fails to support and inspire from a great distance with wry humour and insight.

I’d also like to pass on my thanks to everyone on the team at the Hackney Archive for their helpful advice and enthusiasm.

Finally, three classic historical sources which have proved invaluable:

•

London 1945

by Maureen Waller;

•

Austerity Britain, 1945–1951

by David Kynaston;

•

Family Britain, 1951–1957

by David Kynaston.

ONTENTS

I

NTRODUCTION

3am: Saturday, 27 September 2008

The bedside light clicks on. Wide awake. Again. Another broken night’s sleep. If I read for an hour or so, maybe slumber will return. Reaching out for the pile of unread newspapers by the bed, I pluck a colour supplement from the top of the pile and turn to the first page.

And I can’t quite believe what I’m seeing.

For my weary eye has been instantly drawn to a black-and-white photo in the middle of the page.

It is a powerful image, used to illustrate a historical feature in the

Financial Times

weekend magazine: a throng of City gents at the London Stock Exchange reading the latest newspapers, a fly-on-the-wall reaction shot taken by a

Daily Express

photographer.

And the news that day in 1938 was both dramatic and momentous. Britain’s Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, had returned from a brief visit to Munich to tell the world he’d reached an agreement with Hitler: we would not go to war with Germany.

It was a misleading about-turn in history, an all-too-brief moment of hope, a bleak false dawn that would unravel within twelve months.

Yet it is the pretty young woman at the very centre of the crowd, looking directly at the camera, who really makes the photo come to life. She’s smartly attired: a neat tailored suit, pendant around her neck, jaunty little black hat. And she’s smiling, a youthful smile that somehow embodies the brief optimism of the hour. Close by, a fresh-faced young man with round glasses and wavy hair looks startled, unsure of what’s happening. Somehow the photographer has managed to capture the emotional timbre of the times.

I stare at the photo in total shock, because the youthful couple are my parents, Molly and Ginger, in their courting days, long before I arrived on the scene. I have many black-and-white photos of them after their marriage a few years later. And I will never know what they were doing at the Stock Exchange that historic night. But I had never seen my parents as they were then: so young, so vulnerable, unaware of the mayhem that lay ahead.

What makes the image doubly poignant, however, is the contrast with the present. For the pretty young girl in the picture is now a very frail, confused ninety-two-year-old living in a care home, totally dependent on the support of others. I had visited her hours before, made her a cup of tea and smoothed scented cream onto her wrinkled hands. And although I can’t quite bring myself to acknowledge it right now, her life is slowly ebbing away.

Although I’m excited at having discovered this amazing archive photo in such a random way – I might easily have left the supplement unopened, as happens sometimes with the weekend papers – I am somewhat perplexed at the timing. Why now? Always slightly superstitious, searching for hidden meaning, once I have contacted Getty Images, the photographic archive credited, and confirmed that I can buy my own copy of the photo, I start to wonder: are my parents trying to reach out to me in some way? My dad had died decades before. As for my mother, when I do show her the photo a few days later she does not react in any way. She can’t. Her memory is virtually gone, though thankfully she holds fast to her recognition of me. To her, it’s just a piece of paper. She feels no identifiable relationship with the pretty young girl with the bright smile.

But what are they trying to say, waving at me from the distance of so many decades?

Do they want me to remember their times, what they lived through, how it was for them after the photo was taken, when they and millions of others were plunged headlong into the chaos of World War II?

Or are they merely trying to reassure me, let me know that somehow, they are watching me, looking out for me? This, of course, is a pleasant and comforting thought. But I do not hold any religious beliefs. Nor did my parents. I have long held a half-formed belief that there may be spiritual worlds out there that we don’t quite understand, can’t readily access. My mother too was acutely aware of such things. After my dad died she’d fallen seriously ill. ‘He was trying to take me with him,’ she told me afterwards.

But when I rationalise it, ask myself for the umpteenth time why this photo should fall into my hands now, of course I can’t quite reach any coherent answer. The journalist in me is gratified to see my parents’ image captured at such a significant moment in London’s long history. That will have to do.

Less than a year later, my mother is gone, swiftly and without fuss, after lunch on a summer’s day. It shouldn’t have been a shock, but it turns my world upside down. Our bonds have always been very close, drawn even closer since she became so frail and needy. So I don’t get round to collecting the framed Getty image until months afterwards.

But finally, once it has been carefully hung on my bedroom wall, I start to understand what the image means for me: it’s up to me to tell their story, as I know it, not the history of their respective families or everything that happened to them during their lives, but the story of my childhood, growing up with them in London’s East End after peace had been declared; my own snapshot, if you like, of two decades that were so very different from the world we now live in.

Naturally, I hesitate. It’s not exactly thrilling when you realise that your own life is history, you’ve been around so long that many of your references are unrecognisable, unknown to many. And it’s daunting too because mine was not a joyful childhood, though I’m conscious that I am not alone in this. Do I really want to go there? Should I reach out to exhume the bad moments, the tears, the confusion? They’re not exactly buried deep. So why rake over what is done? After all, I was fortunate; I never knew want or need. And while my relationship with my father was wrecked by his relationship with alcohol and I grew to loathe our environment, my mother was as loving a parent as anyone could ever wish for. Moreover, my subsequent life as a globe-trotting journalist and writer has proved to be as exciting and varied as anyone might desire.