Boost Your Brain (27 page)

Authors: Majid Fotuhi

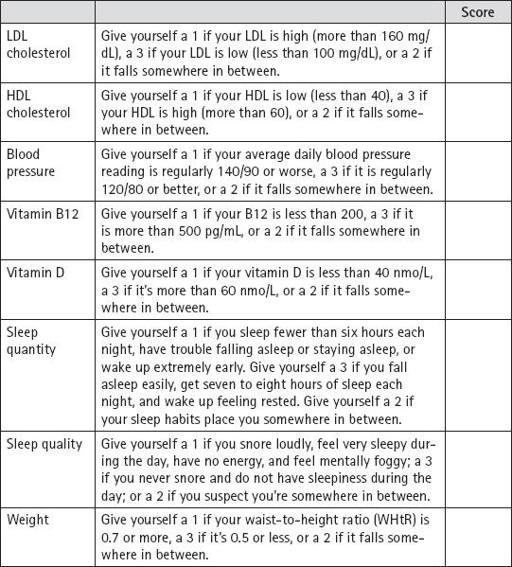

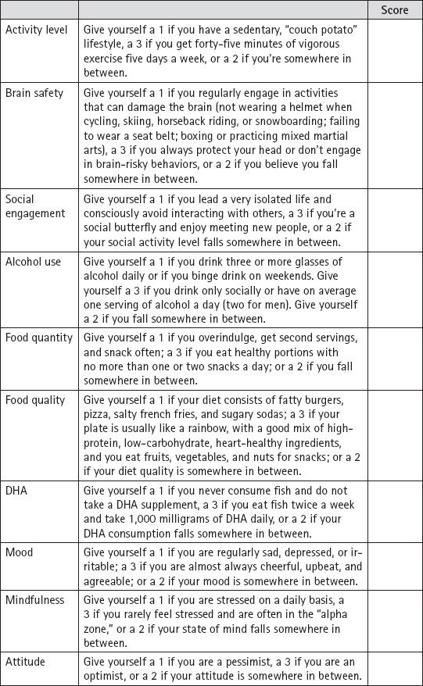

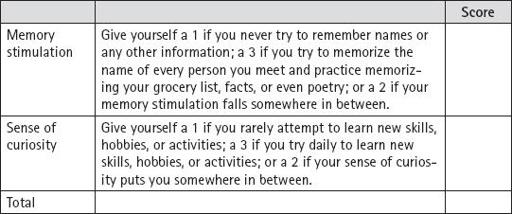

Brain Fitness Calculator

Now, look back to your beginning Fotuhi Brain Fitness Score from page 47 and record it below, along with your finishing score.

Beginning Score ____

Finishing Score ____

Your job in the weeks, months, and years ahead is to maintain or improve your score, living a brain-healthy life that will boost your cognitive performance today and into the future.

Brain Shrinkers You

Should

Live Without

I

F YOU THINK

back to CogniCity, you’ll recall that the metropolis will have plenty of wear and tear to contend with as the years pass. It has roads to repave, buildings to refurbish, parks to maintain, even sewage to dispose of. That’s a lot to take care of. And that’s the best-case scenario. The truth is that there is a good chance that CogniCity will also be the victim of one or more natural disasters over the years. Imagine what happens when a hurricane rolls through. Or a tropical storm. A snowstorm. A tornado. Or all four. If they were minor events, you might expect disruptions in traffic, difficulty conducting business, breakdowns in communication. But a major event—or the combination of several lesser events—could be catastrophic.

An equivalent scenario plays out in the brain. With age, our brains will slowly degrade as a natural result of “wear and tear.” But add to that the effects of disasters, such as out-of-control obesity and diabetes, sky-high blood pressure, severe alcoholism, serious trauma, Alzheimer’s disease, or a major stroke, and your brain will almost certainly suffer the consequences. Combine one or two of these and the effects multiply. The more you add, the greater the impact on the brain. Eventually, with enough disasters—large or small—you might find yourself the victim of serious shrinkage and brain frailty.

But even before then, your brain will feel the effects. You will think more slowly, forget more easily, experience a drain on your creative abilities, and be a poorer problem solver. Your mood may suffer and you may find yourself lacking a zest for life.

And, here’s the kicker: you may not even realize it’s happening. At least not for a while. If you’re like the vast majority of my patients, you might worry vaguely about your memory or slowed thinking, but until symptoms become significant, you’ll simply attribute any lapses to the unavoidable effects of aging or your busy life. In fact, most of my patients have no idea that their mental sluggishness has anything to do with health and lifestyle choices they make every day. Without even realizing it, they’re doing their brains decades of disservice.

You already know about the brain’s incredible potential for growth. Harnessing that power for change is a matter of striking a balance, every day, between brain growers and brain shrinkers. Every brain-healthy choice you make tilts the scale toward growth; every brain-unhealthy choice tips the balance in the opposite direction, with results that are felt both immediately and in the future.

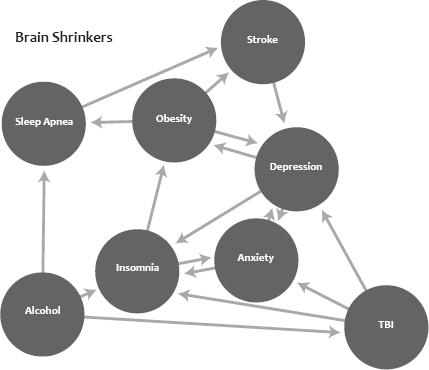

A Web of Trouble

You’re about to learn the major brain shrinkers we encounter in life. But it’s important to know, as you think about how each affects your own brain, that brain shrinkers have a tendency to interact with each other to magnify the disaster.

Sleep disorders, for example, can contribute to other brain-draining conditions, including excess weight, stroke, and depression. As you’ll read in the chapters to come, having one of these conditions may increase your risk of developing another brain-shrinking condition, which in turn may increase your risk of yet another brain-shrinking condition. This often sparks a powerful downward spiral of continued erosion and decline.

How much effect each will have is a matter of degrees: slightly high blood pressure may not shrink your brain, but years of uncontrolled, extreme high blood pressure will. The same applies to small versus large strokes, subtle versus severe sleep apnea, one minor hit to the head versus several large ones, and so on.

The silver lining in this web is that treating one condition may help to reduce your risk of the others as well. Treat them all and you’ll be well on your way to turning that downward spiral on its head and riding the results all the way up to a bigger, better brain.

Shrinking the Brain One Night at a Time

I

T HAPPENS THREE

or four times a week. I’ll ask a patient if she has health concerns and she’ll rattle off a list: high blood pressure, a little extra padding around the waist, headaches, memory problems, fatigue. The one thing my patients often fail to mention is sleep. When I begin to prod them about their nighttime rest, I often hear the same lament. “Oh, I sleep terribly,” they’ll say. “I’m up till midnight and then I wake up at five

A.M.

for no reason. And I’m always tired!”

Often, it becomes apparent as we talk that they suffer from chronic insomnia, yet most have never sought treatment, nor do they realize their problem is almost certainly treatable. In fact, most of my patients who don’t sleep well view their plight as a normal part of life. “Doesn’t everyone have trouble sleeping?” they’ll ask.

The answer is no. Or, rather, it should be no. In fact, insomnia and other sleep disorders are alarmingly common. The Centers for Disease Control calls insufficient sleep a public health epidemic, noting that fifty to seventy million Americans suffer from a sleep disorder.

1

But that doesn’t mean we have to—or should—accept sleep disorders as a part of life. Indeed, doing so presents a real danger to our brains.

If you’ve ever suffered through a sleepless night, you know how it makes you feel the next day: tired, yes, but also foggy, irritable, and a little slow to react. Pull an all-nighter to prepare for a big presentation, for example, and before too long you’ll feel the effects. Without rest, your body and brain lose out on a chance to rejuvenate—and the effect is a hard one to forget.

And while a less-than-stellar day may seem like the worst of it, prolonged periods of poor sleep are likely doing more damage than you imagine. In fact, serious—but fairly common—sleep disorders shrink the hippocampus and cortex, wither blood vessels, and erode the brain’s highways. Even sleep habits that don’t rise to the level of a disorder—like habitually staying up late and waking up early—may be robbing you of brain reserve.

I’m going to detail just how those brain shrinkers make their mark, but first you’ll need to know just why and how we sleep.

A Good Night’s Rest?

According to the National Institutes of Health, about forty million Americans suffer from chronic, long-term sleep disorders each year, with another twenty million saying they occasionally suffer from sleep disorders.

Understanding Sleep

When I visited Florence, Italy, in 2001 I was awed by its historic architecture. But there was something else I noticed, too: the streets and sidewalks were incredibly clean. It wasn’t until I ventured out in the wee hours one night—ironically, thanks to jet-lag-induced insomnia—that I understood why. As most of the city slept, a fleet of trucks and city workers armed with brooms, dustbins, and even high-powered pressure washers, swept and scoured away the day’s grime. When the sun rose, Florence awoke scrubbed and ready for a new day.

In a way, your brain—your CogniCity—is a lot like the city of Florence. By day, it’s hard at work. By nightfall, it has accumulated the wear and tear—and metabolites, in the case of your neurons—to show for it. Your brain needs a good scrub. And while your body rests, your brain’s maintenance crew gets to work, cleaning, rebuilding, and repairing.

Sleep is a fascinating process. Healthy sleep unfolds in a predictable pattern, cycling through periods that are categorized as non-rapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM). NREM accounts for about 75 percent of your night’s sleep and occurs in stages, during which you fall progressively deeper into slumber. During these stages your breathing and heart rate slow down, your body temperature drops, and your brain waves change from the short, spiky waves of an awake brain to longer, slower waves. During your deepest and most restful stages of sleep, your blood pressure drops and your muscles relax. It’s in these stages of deep sleep that you find waking up most difficult.

NREM is followed by REM sleep, an active brain period during which dreaming occurs. Brain waves in REM sleep are short and choppy, similar to those in the awake brain. The body, on the other hand, is inactive (apart from the eyes, which dart under closed lids). You’ll cycle through non-REM and REM sleep all night, with the REM stage becoming longer as the night progresses. As morning approaches, your level of cortisol rises, helping to insure alertness when you awaken.

Although optimal sleep varies by person, most people need an average of seven to eight and a half hours of uninterrupted sleep each night. So says Dr. Helene Emsellem, medical director of the Center for Sleep and Wake Disorders in Chevy Chase, Maryland, and a spokesperson for the National Sleep Foundation. One exception is teens, who need a little more shut-eye than adults—about nine and a quarter hours per night. There may also be rare exceptions for people with genetic differences; researchers have identified one gene whose carriers require as little as five to six hours of sleep a night.

2

But for most people, as Emsellem says, seven hours of sleep is, “the lower legal limit.” Unfortunately, it’s not that unusual to find people whose work, school, or social schedules keep them regularly under that limit. And unlike animals, who “will just go to sleep” when their bodies need it, “humans are Energizer bunnies and will push themselves through on too little sleep,” says Emsellem. They may go for long periods—years or even decades—shorting themselves on much-needed rest.