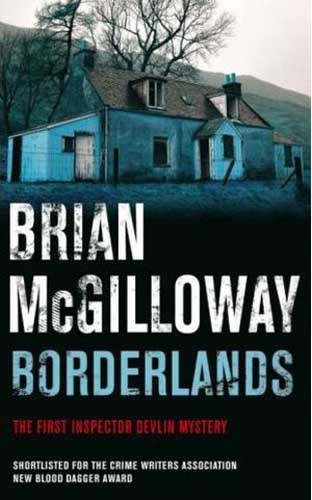

Borderlands

Borderlands

Brian McGilloway

Published 2007 by Macmillan New

Writing,

an imprint of Macmillan

Publishers Ltd

Brunei Road, Basingstoke RG21 6XS

Associated companies throughout

the world

Copyright © Brian McGilloway

For Tanya,

Ben and Tom,

and for my parents

Table of Contents

Chapter One

Saturday, 21st December 2002

It was not

beyond reason that Angela Cashell's final resting place should straddle the border.

Presumably, neither those who dumped her corpse, nor, indeed, those who had

created the border between the North and South of Ireland in 1920, could

understand the vagaries that meant that her body lay half in one country and

half in another, in an area known as the borderlands.

The

peculiarities of the Irish border are famous. Eighty years ago it was drawn

through fields, farms and rivers by civil servants who knew little more about

the area than that which they'd learnt from a map. Now, people live with the

consequences, owning houses where TV licences are bought in the North and the

electricity needed to run them is paid for in the South.

When a

crime occurs in an area not clearly in one jurisdiction or another, both the

Irish Republic's An Garda Siochana and the Police Service of Northern Ireland

work together, each offering all the practical help and advice they can, the

lead detective determined generally by either the location of the body or the

nationality of the victim.

Consequently

then, I stood with my colleagues from An Garda facing our northern counterparts

through the snow-heavy wind which came running up the river. The sky above us,

bruised purple and yellow in the dying sun, promised no reprieve.

We

shook hands, exchanged greetings and moved to where the girl lay, prone but for

one hand, which was turned towards the sky. The medical examiner, a local

doctor named John Mulrooney, was kneeling beside the girl's naked body, testing

her muscles for signs of rigor mortis. Her head rested at his knees. Her hair

was blonde at the ends, but honey-coloured closer to her scalp, her skin white

and clean except for thin scratches across her back and legs caused by the

brambles through which her body had fallen. A SOCO leaned in close to her,

examining the cuts as the medical examiner pointed them out, and took

photographs.

We

watched as three or four Gardai moved in to help turn her over. I stepped back

and stared across the water to the northern side, where the arthritic limbs of

the trees stretched towards the snow clouds, the black branches rattling in the

winter wind.

"Do

you recognize her, sir?" one of the northerners asked, and I turned back

to the girl, whose face was now exposed. My vision blurred momentarily as a

breeze shivered across the river's surface. Then my sight cleared and I moved

over and knelt beside her, suppressing the urge to take off my jacket and

cover her with it, at least until the Scene of Crime Officers were finished.

"That's

Johnny Cashell's girl," a uniformed Garda said, "from Clipton

Place."

I

nodded my agreement. "He's right," I said, turning to the northern

Inspector, a man called Jim Hendry, whose rank was the same as mine but whose

experience was vastly greater. "She's ours, I'm afraid."

He

nodded without looking at me. Hendry was at least a head taller than me, well

over six feet, with a wiry frame and dirty, fair hair. He sported a thin, sandy

moustache at which he tugged when under stress; he did so now. "Poor

girl," he said.

Her

face was fresh and young; she was fifteen or sixteen at most. She wore make-up

in a way that reminded me of my own daughter, Penny, when she played at being a

grown-up with my wife's cosmetics. The blue eye-shadow was too heavily

applied, contrasting with the redness of her eyes where the veins had burst in

her final moments. Her whole face had assumed a light-blue hue. Her mouth was

partially opened in a rictus of pain; the bright red lipstick she had so

carefully applied was smeared across her face in streaks.

Her

small breasts carried purple bruises the size and shape of a man's hands. One

bruise, smaller and darker than the others, resembled a love bite. Snowflakes

settled on her body as gently as kisses and did not melt.

Her

trunk and thighs were ivory white, though her arms and the lower parts of her

legs were tanned with cosmetics, the streaks and misapplication clear now

against her pallor. A pinkish colour was forming on her legs and chest. She

wore plain white cotton pants which were inside out.

"Well,

Doc?" I asked the ME, "What do you think?"

He

stood up and peeled off the rubber gloves he had been wearing. Then he stepped

away from the body and took a cigarette offered to him by a Garda officer.

"Hard to say. The body is fairly stiff, but it was a cold night so I can't

really give you time of death. More than six hours, no more than twelve. You'll

know better when the autopsy's done. Cause of death - I can't be totally sure

either, but I'd say the bruising on her chest is significant. That blue tinting

of the face is caused by smothering or crushing of the chest. That, and the

chest bruising, would suggest suffocation, but that's an educated guess.

Lividity indicates she was moved after she died, though you hardly need me to

tell you that. Naked women don't just appear in the middle of fields."

"Signs

of struggle?" Hendry asked.

"Signs

of something. Her fingernails are bitten so close I doubt you'll get anything

from under them. Sorry I can't be more help, Ben," he said to me. "I

can tell you that she's dead, and that someone killed her and dumped her here,

so it's over to you now. The state pathologist will be here as soon as

possible."

"Presumably

this was sexual," I said.

"Don't

know for sure. The pathologist will take swabs as a matter of course.

Personally, I'd say fairly likely. Good luck, Ben. Take it easy." With

that he dropped the gloves into his case, lifted it and walked up the

embankment to his car, barely looking at the body as he passed it.

I

looked again at the girl. Her hands rested on the leaves beneath her, the

bright red nail polish a little incongruous on fingers so small and on nails

bitten so near to the quick. There was a little dirt around her nails, and soon

enough a SOCO wrapped her hands in plastic bags which he secured at her wrist.

I noticed that, on her right hand, she wore a gold ring set with some type of

stone. It looked too old-fashioned for a girl of her age; a family heirloom, a

gift from a parent or grandparent, perhaps. The stone was tinted green, like a

moonstone, and surrounded by diamonds. I asked the photographer to take a shot

of it. As he did so, the flash illuminated an engraving on the band.

"Looks

like something's written on it, sir," he said, crouching right down and

holding the camera in one hand as he angled her hand slightly with his other.

Then he focused the camera tight on the ring. "I think it says AC, sir:

her initials."

I

nodded for no particular reason and turned again to the group of northerners.

"Shitty

enough one to get the week before Christmas, Devlin. Good luck to you,"

Hendry said, nipping off the end of his cigarette, then putting the butt in

his pocket so as not to contaminate the crime scene. That was a bit of a joke.

Our resources in the arse- end of Donegal are hardly FBI quality and, besides a

dozen or so policemen and the waiting ambulance crew and the group of poachers

who had discovered the body, God only knew how many other people had tramped

back and forth past the body and along the roadway where those who dumped it

must have stopped.

We

would look for distinctive tyre treads, footprints, and so on, and try to find

whatever forensics we could, but the spot where this body had been abandoned,

though secluded, was only a few hundred yards behind the local Cineplex. On

weekend nights this whole stretch of lane was lined with cars, each respecting

the other's space, obeying an unspoken rule of privacy to which I had myself

subscribed when younger, when I was finally allowed to take my father's car to

collect my girlfriend. The makes of cars had changed since then - and I tell

myself, in moments of righteous indignation (though I accept that it's probably

not true), that the kind of activities in which the couples engage has probably

changed too. However, the place remained the same - as dark and furtive as any

of the clumsy embraces which take place on back seats there at night. Indeed,

it was possible that Angela Cashell had met her death in such a car.

"They

might have been from your side," I said to Hendry, motioning towards the top

of the embankment, where those who had left her must have stood.

"They

possibly are," he agreed, "but this one's yours. This must be your

first murder since—"

"1883,"

replied one of ours. "And he was hung!"

"Rightly

bloody so," agreed another northerner.

"Oh,

there's been more since," I said. "We just haven't found all the

bodies yet."

Hendry

laughed. "We'll help any way we can, Devlin, but you're the lead on

this." He looked at Angela one last time. "She was a lovely-looking

girl. I'd hate to have to tell her parents."

"Jesus,

don't talk," I replied. "You don't know her father, Johnny

Cashell."

"Oh,

I know enough," Hendry replied darkly and winked. "British

Intelligence isn't totally down the drain yet." With that, we shook hands

and he walked off towards his own side, steadying himself against the thick

buffets of air carrying the smell of the water across the borderlands.

Johnny

Cashell was known to all the Gardai in Lifford on a first- name basis, having

spent many nights in the holding cell of the small police station in the

centre, of our village. In fact, when the county council recently gave the

whole village a facelift, putting new lamps and hanging-baskets all around the

cobbled square and benches along the main roads, we named the bench outside the

station "Sadie's", in recognition of the amount of time spent on it

by Cashell's wife while she waited for him to be released in the morning from

the drunk-tank.