BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (30 page)

Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

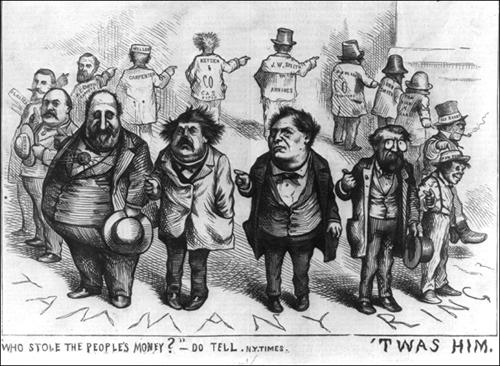

Harper’s Weekly, August 19, 1871.

The clever caricatures couldn’t help but produce a chuckle. “You have never done anything more trenchantly witty than the ‘Co.’ of Ingersoll… and the ‘’Twas him!’” Nast’s editor George W. Curtis wrote him that week. “My wife and I laughed continuously over them. They were prodigiously good.”

56

Tweed certainly didn’t laughed, but he recognized the point: Millions had been stolen—but by whom? Until a specific person could be proven guilty, all remained innocent. Still, he and Connolly took precautions. On August 16, Tweed executed deeds transferring at least seven parcels of real estate to his son Richard—including the “circle property” (today’s Columbus Circle), his farm at Fort Washington, and his home on Fifth Avenue and 43rd Street—to shield them from creditors, though he didn’t actually file the deeds; he simply held on to them. About the same time, Mary Connolly, Connolly’s wife, transferred ownership of $500,000 in United States treasury bonds from her own name to that of her son-in-law Joel Fithian.

57

All the while, the drumbeat grew. On August 28, the German Democratic Union met and passed a series of anti-Tweed resolutions;

58

on September 2, the City Council of Political Reform met to raise money for waging court fights against the Ring.

59

Even among its friends, Tammany’s prospects had soured. “They are since July public enemies,”

New York World

managing editor David Croly privately told his publisher Manton Marble. “The

World

blundered terribly in supporting them.” He quoted a source who’d spoken with the mayor as saying “no honest defense of the city of the present state of city finances is possible [and] any defense of the Ring can only bring shame and confusion on its defenders when the facts come out.”

60

In a few days, New York’s wealthy elitists would return from their summer holidays for their mass meeting. A feeling of imminence hung in the air. The moment was ripe for

coup d’etat

; it waited only for a qualified plotter to come along.

CHAPTER 13

TILDEN

“ I think a spasm of virtue will run through the body politic. Business is dull.”

—Horatio Seymour, writing to Tilden from upstate New York, August 12, 1871.

“ Sam Tilden wants to overthrow Tammany Hall. He wants to drive me out of politics. He wants to stop the pickings, starve out the boys, and run the government of the city as if ‘twas a blanked little country store up in New Lebanon… He wants to get a crowd of canting reformers in the Legislature, who will talk about the centrifugal force of the Government…; and then, when he gets everything all fixed to suit him, he wants to go to the United States Senate.”

—Tweed, responding privately in 1869 to the question: “What does Tilden want?”

1

S

AMUEL Tilden spent July at home in New York that year minding his business while enjoying his Gramercy Park townhouse, horse-riding in Central Park, and dinners at the Manhattan Club. He tended his railroad clients from his law office on Wall Street, a third story suite with three large rooms and plenty of sunshine. Its library held over 4,000 books and its walls held portraits of political heroes like General George B. McClellan and former Governor Horatio Seymour. Tilden delighted passing time there. He mostly avoided politics these days; he presided as state party chairman but stayed away from the Tweed-dominated state legislature. He had better things to do.

Like everyone around him, Tilden took time between concerts, dinner parties, and office work in July to follow the dramatic Secret Account disclosures in the

New-York Times

. He read the banner headlines, talked them over with friends and heard the reactions around town. He claimed to doubt the

Times

’ charges at first; the articles made a strong case for theft—a “moral conviction of gross frauds,” as he put it—but the numbers seemed far-fetched. He’d always assumed Tweed corrupt, but never expected the scale to be so large.

2

Early that August, Tilden left Manhattan for a short vacation and brought a stack of the

Times

articles along to study. Traveling north by train, he reached New Lebanon, the tiny upstate hamlet at the base of the Berkshire Mountains where he’d spent his boyhood and where his two brothers still lived; here, Tilden took the time to read the articles more closely. What he saw alarmed him, the political fallout especially. As he saw it, the Tammany scandal threatened to sink not just Tweed’s circle but the entire state Party, and Tilden with it. “I think you had better note the tone of the 30 or 40 extracts which the

Times

daily publishes from journals of all parts of the United States [showing that] the evils and abuses in the local government of the city of New York are general characteristics of the Democratic party,” he wrote his friend and

Albany Argus

publisher William Cassidy that week.

3

One particular

Times

column must have made him gasp: “Where are the Honest Democrats?” it asked, naming Tilden specifically as shamefully silent.

4

He began hearing nervous calls from friends across the state. “Is it not a good time to dismember the New York ring?” Judge Samuel Church wrote him from Albion, a small town in western New York near Lake Ontario.

5

After a few days in New Lebanon, Tilden left his family and visited Albany where he met former Congressman Francis Kernan returning from the seashore. Together, he and Kernan traveled up the Mohawk River to Utica and visited former Governor Horatio Seymour at his farm. On his way back, Tilden stopped at Saratoga to enjoy the horse racing and social hobnobbing; here he ran into George Jones of the

New-York Times

—himself taking a few days off for a summer break. Tilden described Jones as looking exhausted from his Tammany fight. “I told him I should appear in the field at the proper time,” Tilden said. Jimmy O’Brien too apparently came to Saratoga that week and bent Tilden’s ear.

6

By the time Tilden returned to New York City on August 10, all these talks had brought him to a decision: Tweed had to be toppled. He became strident in his private conversations. “We have to face the question, whether we will fall with the wrongdoers or whether we will separate from them and take our chances of possible defeat now, with resurrection hereafter,” he wrote Rochester newspaper publisher William Purcell, telling him his

Rochester Union and Advertiser

must “begin at once prudently to disavow and denounce the wrongdoers, and educate our people.”

7

Tilden buttonholed

New York World

managing editor David Croly and told him his newspaper must abandon its defense of Tweed.

8

He got encouragement for this tough talk: A “financial gentleman” representing angry Wall Street investors came to see him one night and explained the financial impact of the crisis, and Horatio Seymour wrote him letters from upstate Utica laying out the scandal’s wider political dimension. “When the public mind is turned to the question of frauds, etc. etc., … there will be a call for the books at Washington [President Grant’s scandals] as well as in the city of New York,” Seymour explained. “We can lose nothing by stirring up questions of frauds.”

9

All this talk was private, though. Publicly, Tilden remained invisible. He made no speeches, gave no interviews, and refused to reveal his plans even to close friends like Manton Marble and August Belmont. Secrecy, he decided, was essential for any plan to work. He began to weigh options: Statewide elections were scheduled for November that presented a chance to break Tweed’s hold on the Albany legislature and, with it, perhaps to overturn his city charter. Tilden also visited lawyer Charles O’Conor to discuss whether the state government in Albany might have grounds to sue Tweed for stolen funds.

But Tilden knew these steps were only window dressing. His lawyer’s eye had caught the fatal flaw in the

New-York Times’

case against Tweed. The Secret Accounts demonstrated that

someone

had robbed the city, but they failed to show

who

. Without a direct link connecting the crime to a specific person, he’d never be able to bring legal action against anyone.

10

Tweed could hide behind Connolly, Connolly behind Garvey or Ingersoll, the contractors behind Oakey Hall—just as in Thomas Nast’s cartoon, each man pointing to the next and saying “’Twas him.” They’d all walk free.

To transform the Secret Accounts into a rock-solid legal case against a specific villain meant solving a puzzle, the kind that set Tilden’s mind aglow.

Ever since childhood, young Sammy Tilden had loved games and puzzles, especially involving numbers. He’d shown his brilliance many times: As a young lawyer in 1855, Tilden had once represented a political friend named Azariah Flagg who claimed he’d been cheated out of his election as New York City’s comptroller by a Know-Nothing candidate with a razor-thin margin of 179 votes. The case looked hopeless. It all boiled down to a certified return from a single election district that gave Flagg a 316 to 186 majority: Lawyers for the Know-Nothings produced a stable of witnesses—two voting inspectors, an election clerk, and others who’d claimed to see the actual count—all of whom swore that these numbers had been reversed by a clerical error and that Flagg’s opponent had actually won the majority, tipping the race his way.

Tilden knew they were lying, but he couldn’t accuse all these men of perjury without proof and the tally sheets showing the number of “regular” votes cast had conveniently disappeared. These “regular” votes—ballots cast for a full slate of candidates for each of the contested positions—could have helped him reconstruct the lost tally sheets; without them, he had nothing.

Rather than giving up, though, Tilden spent two nights thinking about the issue. Pieces of the puzzle dangled before him: Could he not reconstruct the missing tally sheets based on what he

did

know: the total number of “regular” ballots, the number of “split” ballots (those where a voter deleted one or more names from the slate), and the number of votes cast for each candidate in each of the eleven

un

contested races? Counting backward from the

other

races, perhaps he could fill in the gaps. For instance, if Samuel Allen, the candidate for street commissioner, had received 215 “regular” votes on the same slate as Flagg in a given ward, than Flagg must have received the same 215 votes.

Tilden asked a Columbia College mathematics professor named Henry J. Anderson to help him devise a formula using the evidence at hand. By the time the trial reconvened, Tilden had finished the job. Standing to address the jury, he startled the packed courtroom: “I propose now, gentlemen, to submit this case to a process as certain as a geometrical demonstration.

I propose to evoke from the grave that lost tally

.”

11

How? “If, by a violent blow, I should break out the corner of this table, split a piece off, the fractured and abraded fibers of the wood would be left in forms so peculiar that, though all human ingenuity might be employed to fashion a piece that would fit in its place… it could not be done. So it is with truth. It is consistent with itself.”

12

Tilden then handed out a vote tally sheet he’d reconstructed using his mathematical process and explained the logic step by step—adding Flagg’s share of each of the other candidates’ “regular” tallies, then calculating his remaining “split” votes. He’d won the case before calling a single witness; the jury deliberated less than fifteen minutes before declaring Flagg the winner.

Now, in 1871, Sam Tilden again saw a puzzle dancing before him, a mass of numbers begging for a pattern: the

New-York Times’

Secret Accounts. This puzzle too must have an answer, a key to trace stolen city funds through the maze of vouchers, warrants and bank accounts directly to the personal pockets of Tweed and friends—proof that would put them all behind bars. To find it, he’d need more information: data from the inner sanctum of city finance, the Comptroller’s Office in the new courthouse on Chambers Street. Richard Connolly, the comptroller, would be the key.

Tilden shared his thoughts with no one. If his secretiveness irritated his friends, so be it. “Tilden is very positive in his views, but rather shrinks from what he has got to do,” one insider grumbled. “He has no sympathy for the Ring but sees its power. He is bitterly hostile to the whole gang.”

13

Sam Tilden wasn’t looking to make friends or headlines in the late summer of 1871. He was looking to take down Tweed, to lunge without warning, aiming straight at the heart.

-------------------------

In early September came the long awaited mass meeting of city “respectables” to protest the Tammany Ring and George Jones, the night’s most-honored guest, had to marvel at his good fortune. After almost a full year leading his

New-York Times

in its lonely fight against Tammany Hall, being harassed, ostracized, and threatened, he found himself tonight the center of attention.

The turnout for the anti-Tammany meeting far surpassed anything its organizers had hoped for. Thousands came, forcing them to change the venue from the Academy of Music to the much larger Cooper Union at Third Avenue and Astor Place. Half an hour before its scheduled start, swarms of men in suit jackets, some wearing top hats, women with bonnets and parasols, and merchants in swallowtail coats—a well dressed, respectable crowd—crammed into the Cooper Union’s Great Hall, the same room where Abraham Lincoln had delivered his famous speech in 1860. They filled its every corner, clogged the hallways and haggled over tickets, clamoring to get inside. Carriages jammed nearby streets and overflow crowds flooded the sidewalk; a separate platform with speakers had to be improvised on the street to accommodate them. More than a hundred police officers came to keep order.

Inside the hall, beneath its high ceilings, glass chandeliers, and calcium lights, hundreds of chairs crowded the stage for special guests. These included dozens of speakers and over two hundred honorary “vice presidents,” and a special place for George Jones of the

New-York Times

.

Times

reporters circulated through the room, preparing to cover the paper’s front page with the story.

By the time the meeting started, Jones sat on stage surrounded by a tightly-packed throng of people, cheering, shouting, waving handkerchiefs, many stopping to shake his hand, pat his back, and congratulate him. They’d finally joined his crusade. His sense of vindication must have been profound. His worst enemies these days were fellow Park Row publishers jealous of his success: “The

Times

rolls itself up like a porcupine and shoots out its venomous little quills alike at friend and foe,” Horace Greeley grumbled in the

Tribune

;

14

James Gordon Bennett Jr.’s

Herald

called the

Times

a “political guerilla” with “English cockney proclivities.”

15