BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (26 page)

Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

For the same issue, Nast penciled a cartoon ridiculing Oakey Hall by turning him into a horse, “The Mare,” sick with “The New Horse Plague.” “Mare” Hall stood in a stable as Tweed (diamond as usual) and Sweeny (dark presence at Tweed’s side as usual) look on.

31

In Nast’s mind’s eye, the images all seemed to merge now in a powerful creative surge: He had enemies to knock down—Tweed, Tammany, the Irish—and the new disclosures in the

New-York Times

of graft-ridden city spending gave his work urgency.

Readers began snatching up newsstand copies of the

Weekly

as much to laugh at Nast’s latest satire as to gasp at the illustrations of the Orange riot and its aftermath. Pictures more than words became their staple.

-------------------------

A panel from Nast’s epic portrayal of the Battle of Eighth Avenue, Harper’s Weekly, July 29, 1871.

George Jones, after ten months of shadow-boxing with Tammany Hall, had grown wary. Before giving his editor Louis Jennings final approval to unleash his final grand assault against Tweed, he wanted to tie up one last loose end. Jones still fretted over his Achilles heel: the 34 shares of

New-York Times

company stock still owned by Henry Raymond’s widow and the threat that Tweed still might use it to steal his newspaper once the fight began.

In early July, George Jones found his answer in E.B. Morgan, an old friend from Albany who’d made his fortune on the Wells Fargo stagecoach company and had retired in upstate New York. Morgan had been an original investor in the

New-York Times

twenty years earlier and he and Jones had kept in touch over the years. Hearing from Jones about the recent threats from Tammany Hall, “The old Colonel [Morgan] was angry right down to his woolen socks,” a

Times

assistant recalled.

32

Morgan, happy to help and rich enough to do it, rushed down to New York City and within a few days handed Mrs. Raymond a $370,000 payment to buy her entire stake in the company at $11,000 per share—a growth of more than 1,000 percent from its original value.

“The shares in the

New-York Times

attached to the Raymond estate, representing about one third of the property, were yesterday purchased by Mr. E.B. Morgan, of Aurora, Cayuga County [in upstate New York],” Jones announced publicly on July 19. He and Morgan now directly held eighty-two percent of the

Times,

a solid enough hold to scare away any back-room suitor.

33

That done, he now gave Jennings the signal to strike.

For a full day after receiving his surprise visit from Jimmy O’Brien and his envelope stuffed with hand-copied city account records, Louis Jennings had pawed through the material. He and his writing team, John Foord and Matthew O’Rourke—the original source of the armory data whom Jennings had now hired onto the newspaper’s staff—spent hours dissecting the vast array of data. O’Brien’s envelope had contained entire ledger accounts hand-copied by his friend William Copeland. O’Rourke and Foord scoured the mass of numbers looking for patterns, using O’Rourke’s own stolen numbers as well as public financial reports on city and county debt to fill gaps. Fitting together the story piece by piece, they worked in secret. Jennings had no intention of risking last-minute foul play by tipping his hand, asking Tweed, Connolly, or Hall for comments or verifying the ledgers with the city.

Beyond security, Jennings and his team faced a daunting challenge as writers: how to explain the sheer mountain of complexity, three years’ worth of detailed account records with hundreds of entries, in a way to convey its meaning while grabbing attention. Their strongest weapon appeared to be the raw numbers themselves—numbingly detailed but intimate and personal. With work, they realized, they could turn the dry account books into a voyeuristic sensation, a visual image as stark as anything from the pencil of Nast.

Jennings approached the job as if staging a drama for his wife, the actress at Wallack’s theater. His would be a three-act play, starting with curtain raisers designed to build suspense. He began with foreshadow: On Wednesday, July 20, he alerted the city that a great secret would soon be revealed: “Tomorrow morning we shall publish a still more important document, also compiled from Connolly’s own books,” he warned in an editorial titled “Two Thieves.” “We shall prove … that the public are robbed of several millions a year under the armory accounts alone.” But even this was mere appetizer: “Our article tomorrow, though of great import, will be exceeded in interest by a true copy which we shall shortly publish of the money paid on warrants… for the new Court-house.”

34

Each day that week, he banged the drum: On Thursday, the

Times

carried new accusations about city spending on armories: focusing on the $941,453.86 paid for “repairs” during a nine-month period, all going to four contractors. “[T]hey charged the money to the city, and divided the money among themselves, and this, we say was robbery,” it claimed. Oakey Hall and Connolly, who signed and approved the payments, were “the chief thieves.”

F

OOTNOTE

35

Then on Friday, he alerted the city again; more secrets were coming. “Will It ‘Blow Over?’” he asked in an editorial. He described Connolly’s office, where the city’s accounts were kept, as being “guarded … with fixed bayonets.” What awful secrets must it hold? “We have however, not yet begun to tell the story.”

36

“[Mayor] Hall goes about assuring every body who will listen him that he is ‘used to newspaper attacks,’” the

Times

said. On Saturday would come the biggest attack of all.

CHAPTER 11

DISCLOSURE

“THE SECRET ACCOUNTS.

“Proofs of Undoubted Frauds Brought to Light."

“Warrants Signed by Hall and Connolly Under False Pretenses."

“The Account of Ingersoll and Company.”

“The following accounts, copied with scrupulous fidelity from Controller Connolly’s books, require little explanation….”

—Front page headline, three columns wide, the first banner in the

New-York Times

’ history.

New-York Times

, Saturday, July 22, 1871

N

OTHING like it had ever appeared before in an American newspaper. “THE SECRET ACCOUNTS,” screamed the headline. Underneath it, covering fully half the front page, appeared a simple list of ledger entries, bare, naked, unadorned—136 line items altogether, exact to the penny, totaling $5,663,646.83.

1

Each line alone looked innocuous: “Sept. 28—Paid for repairs to County Offices and Buildings, July 2, 1869… $48,798.62” or “May 27—Paid for Cabinetwork Furnished in County Court-House, Aug. 23, 1869… $125,830.” Together, they painted a stunning portrait—geysers of cash flying out from the city treasury, amounts impossibly large for their stated purpose. They raised an obvious question: Where had all the money gone? The implicit answer: fraud, waste, and God-knows-what. “The following accounts, copied with scrupulous fidelity from Controller Connolly’s books require little explanation. They purport to show the amount paid during 1869 and 1870 for repairs and furniture for the New Court-House,” read a brief headnote.

The new Courthouse, which housed the Comptroller’s Office, they would make Tweed’s signature building.

Not only were the amounts exorbitant, but the Times showed how all the money eventually went to a single account, “Ingersoll and Company,” even though the warrants had named a dozen different companies as payees. “Ingersoll & Company,” it turned out, belonged to James H. Ingersoll, a long-time family friend of Tweed, one-time business partner with Tweed’s brother Richard, and son of a one-time partner of Tweed’s father. “What amount of money was actually paid to the persons in whose favor the warrants were nominally drawn, we have no means of knowing. On the face of the accounts, however, it is clear that the bulk of the money somehow or other got back to the Ring,”—How? It didn’t say.—“or each warrant would have been endorsed over to its agent.”

Saturday’s blast was the first installment, the next two coming on Monday and Wednesday, July 24, and 26. Each followed the same pattern: the huge front page layout of ledger entries showing payments to contractors too impossibly large to be real.

Monday’s list covered warrants for payments to Andrew Garvey for “plastering and repairs”—$2,870,464.06 total over two years, “copied verbatim from the Comptroller’s books—the books entitled the ‘Register of Warrants’ and the ‘Book of Vouchers’” as if citing volumes of scripture. In an editorial, Jennings dubbed Garvey the “Prince of Plasterers” and ridiculed his claims as reflecting “repairs” to the new courthouse just recently opened. He pinpointed items showing $126,578 received by two contractors for four days’ work and concluded with another mystery: “How much money these persons actually received … they might be forced to testify under oath, but are probably not willing to inform us.”

Wednesday revealed payments to Keyser & Company, plumbers and gasfitters—totaling over $1.2 million in two years. “We have seen what a good thing it is to be appointed furniture-dealer, or carpenter, or plasterer, or plumber, under the City authorities,” Jennings wrote.

2

He asked how carpenters could be paid hundreds of thousands of dollars on a courthouse “chiefly constructed of marble and iron—there is very little woodwork in it.” He highlighted $170,727.60 paid to Ingersoll to supply chairs to armories which, at $5 each, would buy “314,145 chairs, and if placed in a straight row these chairs would have reached over 85,363 feet, or about 17 miles…. Even at $25 each they could stretch from the City Hall Park to Forty-second-street.” And then came the $2,817,469.19 paid for cabinets and furniture, enough to furnish “nearly three hundred homes on Fifth avenue, from Washington-square to Thirtieth street, on both sides of the street.”

3

“[S]crutinize them, analyze them, test them thoroughly,” the Times told its readers. And in fact, readers began snatching up its 4-penny newsstand copies. Politics aside, the Secret Accounts made good theatre. The ledgers, authentically raw and bare, tantalized the eye, like stealing a glance at a stranger’s diary, peering into a neighbor’s window, or happening to see a friend’s bank balance—things hidden made glaringly public. Even the name “Secret Accounts” evoked mystery. The ledgers raised endless questions. “Observe—we are only quoting County accounts. The City accounts reveal fraud of still greater magnitude: but we speak now only of what we can prove,” the Times explained; “We will not… analyze these figures today. They speak for themselves.”

Jennings used his editorials to point a special accusing finger at the city blue-bloods who’d embarrassed the Times by giving Tweed’s finances their blessing back in November: “Did John Jacob Astor, Moses Taylor and Marshall O. Roberts see the accounts now published on our front page when they signed their certificate?” he asked. “If they did see them, what right had they to certify that the Comptroller’s accounts were all right?”

Each day that week, Jennings and his writers pounded their message, repeating highlights over and again. They listed a carpenter named George S. Miller, for instance, as receiving nine warrants in a single month for work on the courthouse totaling $360,751.61. “Is not this Miller the luckiest carpenter that ever lived?” They listed purchased carpets for the courthouse and county buildings totaling $565,731.34; at $5 per yard, that was “money enough for carpets in the new Courthouse alone to have covered the whole City Park three times over.”

4

A strip a foot wide “would go nearly from New-York to New Haven, or half way to Albany, or four times from the Battery to Yonkers, or from Albany to Oswego.”

5

They pointed to another $636,079.05 for work supposedly done on Sundays when the buildings were closed. On Friday that week, Jennings dramatized the fake names they found in the account books by sending one reporter to the Comptroller’s Office asking “Who is A.G. Miller?” and another to downtown rug-dealers looking for a “J.A. Smith”

6

—names that Ingersoll himself later would admit to be fictional—and turning their wild-goose chases into comic front-page copy.

Who was the “Company” in Ingersoll and Company, he asked? The answer, by implication, was Tweed.

F

OOTNOTE

7

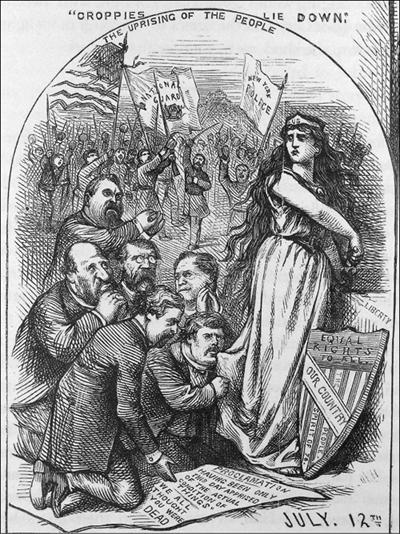

Harper’s Weekly, August 19, 1871.

Capping the week, on Saturday, July 29, the Times issued a pamphlet called “How New York Is Governed: Frauds of the Tammany Democrats” that contained a full set of the Secret Accounts, all the ledgers they’d printed on the front page covering over $12 million in city payouts. New Yorkers grabbed them as fast as they came off the presses. Trucks and mail wagons lined up at the Times building from early morning until late that night carrying bundles to newsstands throughout the city. The pamphlet’s initial print run of 220,000 copies—the largest ever yet for the Times—sold out within hours. For the entire next week, George Jones directed the Times’ Hoe steam presses to work overtime cranking out more; ultimately they sold over 500,000 copies, including a German-language edition, this too a first in the newspaper’s history.

The word was out; the charges had been made. Now, the question on everyone’s lips was: What would Tweed say?

-------------------------

One night about this time, a messenger interrupted George Jones while he was working at his desk in his corner office at the New-York Times. A tenant in the building, a lawyer who rented office space, needed to see him urgently. Jones got up from his desk and walked over to the lawyer’s office, but on opening the door he found a surprise. Instead of his tenant, waiting there to meet him was Richard Connolly, the tall Irishman with the sharp eye, clean-shaven face, and stovepipe hat whom Jones’ newspaper for months had been calling “Slippery Dick,” chief swindler of the Tammany Ring. “I don’t want to see this man,” Jones said; he quickly turned to leave.

8

Jones could guess what Connolly wanted—another trick to steal his newspaper, intimidate his employees, or insult him with bribes. Jones claims that he’d already been buttonholed earlier that month by a Tammany agent offering to buy his stake in the newspaper “at any valuation that might be put on it,” he said. “This offer was made in cash, to be paid at once.”

9

“For God’s sake! Let me say one word to you,” Connolly’s blurted out. “For God’s sake, try and stop these attacks! You can have anything you want. If five millions [of dollars] are needed, you shall have it in five minutes.”

10

George Jones stood at the door; if he savored this moment, he didn’t show it. The sheer size of the offer—equal to about $100 million in modern dollars—apparently caught him breathless. He remembered answering wryly: “I don’t think the devil will ever make a higher bid for me than that.”

“Why, with that sum you could go to Europe and live like a prince.”

“Yes,” Jones said, “but I should know that I was a rascal. I cannot consider your offer or any not to publish the facts in my possession.”

F

OOTNOTE

As a young boy in rural Vermont, George Jones’ childhood friend Horace Greeley had once convinced him to skip church on a Sunday for a “loafing expedition” in the woods. When Jones came home later that day, his father, a strict Baptist, confronted him. “I have been over the hills with Greeley studying nature,” Jones remembered telling his father, who wasn’t amused. “Indeed!” his father said, “well, then, come into the wood-shed and we will have another lesson in the study of nature.” Jones’ father had died a few years later, but young George recalled the “lesson” he learned in the woodshed that day. As a 70-year-old man, he would still point to it as a key event in his life.

11

Now, fifty years later, these roles seemed reversed. Horace Greeley, now the venerable publisher of the New York Tribune who knew the power of scandal to sell newspapers and once observed “[t]he public run instinctively to a dog fight,”

12

now counseled caution: “We have scrupulously refrained from the intemperate style of attack in which the Times has of late profusely indulged because words thus lose their force and because we did not have proofs to warrant charges which nevertheless we have often believed to be true,” Greeley wrote in the Tribune.

13

“We do not indorse it neither do we discredit [the Times’ charges]. We are not in possession of facts that would warrant us in making such charges… If it be justified by facts Messrs. Hall and Connolly ought now to be cutting stone in a state prison.”

14

Others of Jones’s old friends in New York journalism likewise took a balanced view of the Tammany affair: “We may remark that a little more moderation in epithet would not detract from the Times’s case,” E.L. Godkin, himself a former Times editorial writer who’d known George Jones as the quiet financier of earlier days, wrote in The Nation. “The bladder with beans in it, as well as the lash, is audible after some of its strokes.”

15

Just two years after inheriting the paper from Henry Raymond, conservative, serious George Jones had not only survived as owner of the New-York Times but had produced the most ground-breaking, controversial story of his era. After seeing Connolly that day, he went back to work and never said a word of it in his newspaper until years later.