BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (22 page)

Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

“[A]s soon as the Hon. A. O’Hall has completed his term as mayor,” the article went on, “he will become the editor [of the

Times

], and then the political character of the concern will doubtless be changed.” Jones knew that the

Times

under Elegant Oakey’s control would be a Tammany pawn with no more credibility than the

Leader

, the

Star

, or the

World

.

Forewarned was forearmed. Politicians had tried to silence newspapers in America from the days of John Peter Zenger to John Adams’ “Alien and Sedition” acts.

F

OOTNOTE

To keep his newspaper and fight off this new threat of Boss Tweed wielding the power of cash back by crooked judges, George Jones would need to keep his nerve. Fortunately for him, he still had a powerful weapon in this fight, the newspaper itself. Now he would have to learn how to use it.

-------------------------

Thomas Nast still preferred to work at home on his

Harper’s Weekly

drawings, though success had given him the money to move north out of the city with Sarah and the children to a house in Harlem at 24 West 125th Street. He rode the train down to the city and Franklin Square only occasionally to see his publisher and deliver his latest works. It was here he heard the news, probably from Fletcher Harper directly: Tammany had found a way to blackmail Harper’s company. Fletcher and his brothers took the threat seriously and had called a meeting to discuss it. At issue was whether to silence Nast and the

Weekly’s

campaign against Tweed. The cost had grown too high.

The actual threat involved textbooks that Harper produced and sold to New York City schools, normally tens of thousands each year comprising a major source of income for the company. Harper had learned that the Board of Education had decided to reject any future books from the company and to throw out all Harper books it currently had in stock. These existing textbooks included standards like

Willson’s Reader

and

Frenon’s Arithmetic

; the city would replace them with new books ordered from the New-York Printing Company, Tweed’s firm.

James Harper, oldest of the four brothers who’d founded the company in the 1820s, had died in March 1869; now, of the remaining three, Fletcher feared he might be alone in wanting to resist the pressure. His older brothers, 76-year-old John and 70-year-old Joseph Wesley, sympathized, but they had a business to run, hundreds of employees to pay, and could not afford to lose their largest single customer. If City Hall boycotted Harper’s textbooks, others might join them. The financial impact on the company if several large customers abandoned them in sympathy with City Hall could be devastating. Harper estimated the value of the existing textbooks alone at $50,000.

Nast’s friends had warned him this could happen. “They will kill off your work,” his cousin James Parton had cautioned months earlier. “You come out once a week—they will attack you daily. They will print their lies in large type, and when any contradiction is necessary it will be lost in an obscure corner.”

23

Nast probably didn’t believe it; he had a national reputation and made good money. Ulysses Grant himself had praised him for his role in the 1868 political campaign: “Two things elected me [as president],” Grant had said, “The sword of Sheridan and the pencil of Thomas Nast.”

24

Nast had recently sold a single drawing for $350, the largest amount ever paid for such a work, and he had well-paying contracts to illustrate editions of

Humty Dumty

and

Dame Europa’s School

for a British publisher.

25

News clippings guessed his personal wealth at the time at $75,000, a huge sum for a mere newspaperman or illustrator.

26

Nast wasn’t shy about promoting his work: “Please see my picture

exhibited

again tonight [at the] seventh regiment armory,” he’d telegraphed to

Tribune

editor John Russell Young to guarantee publicity for one particular show.

27

But Tammany was a different animal altogether; Nast began to hear rumors about himself circulated around town—that he’d fled Germany to avoid military service, for instance, despite his being only six years old on reaching America.

Nast had always thrown himself into crusades. When he rode with Garibaldi on his “march of conquest” across Italy back in 1860, young Tommy had become a shameless follower of the “liberator,” dressing like the soldiers in red shirt, Garibaldian hat and bandana, joining their marches and sharing their confidence. He’d followed Garibaldi on his triumphant entry into Naples and drew the hero’s portrait, both on Garibaldi’s handing the newly united country to King Victor Emmanuel and then on departing humbly to his home in Caprera, the small island near Sandinia.

Later, back in New York when he’d briefly re-joined

Leslie’s Illustrated

, Nast had participated in

Leslie’s

crusade against polluted “swill milk” sold in the city from diseased cows. He drew pictures of infected barns and sick animals and saw his publisher at

Leslie’s

stand firm when angry dairymen threatened his life. This experience, plus the Civil War, had taught Nast to see political issues as stark moral choices, questions of wrong versus right, evil versus good.

For Nast, lampooning Tammany Hall had begun almost by reflex. City corruption was a natural target. People saw it all around them: police officers demanding payoffs from gambling dens or brothels, repeaters on Election Day, ward politicians with fat bankrolls. Nobody doubted that thieves haunted City Hall. In late 1869, at the height of a campaign by Tweed to depose August Belmont as national Democratic chairman, Nast had penciled a cartoon of Belmont as “The Democratic Scapegoat”—complete with horns and hooves—loaded down with sacks labeled “Sins of the Democrats.” Tweed had appeared only as a face in the background, Nast’s first depiction of the Boss.

28

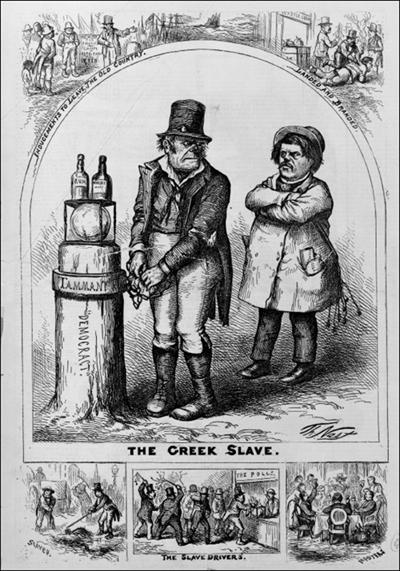

A few months later in mid-1870, Nast portrayed Peter Sweeny as Tammany’s villain-in-chief in a cartoon called “Greek Slave;” it showed Sweeny, whip in hand, bullying an Irishman chained to a pillory marked “Tammany,” fed rum and whiskey and led by “slave drivers” to the ballot box.

29

Over the next few months, as Tweed emerged as the dominant personality in city politics, Nast found him an irresistible subject: the easiest to draw of the Tammany crowd with his big belly, big nose, and silly grin. Just before the 1870 election, he moved Tweed into the foreground. One cartoon, “The Power Behind the Throne,” showed Governor John Hoffman still the front-man sitting as monarch but with Tweed at his shoulder wielding a sword of “power.” Another drawing, called “Our Modern Falstaff,” showed jolly fat Tweed dressed like a clown while reviewing his brigade of Irish “repeaters,” Hoffman reduced to merely a midget at Tweed’s side.

30

In April, he made Tweed a Napoleon on the battlefield: “Emperor Tweed” leading his political troops through the a “Baptism of Fire” with “Political Reform” bombs exploding overhead.

31

Nast and

Harper’s

had not a shred of evidence against the Boss. Instead, they pointed to the “universal conviction” that Tammany was corrupt, a fact “familiar to every citizen” and “universally understood.”

32

Nast used symbols to exploit his readers’ prejudice: against the showy rich, against immigrants, against politicians. He sprinkled his Tweed drawings with recurring features: Tweed’s big diamond, the brute Irishman—always with a threatening look, dirty clothes, a battered hat, over-sized skull, and whiskey bottle—and the Tammany tiger.

Nast’s typical Irishman, being corralled by Peter Sweeny to back the Tammany line. Harper’s Weekly, April 16, 1870.

His anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic slant fit comfortably at

Harper’s.

James Harper, the eldest founding brother, had been elected mayor of New York City in 1844 heading an anti-immigrant movement called the American Republican Party—a forerunner of the Know-Nothings. The Harper company itself had then recently published the American edition of

The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, or The Hidden Secret of a Nun’s Life in a Convent Exposed

, alleging wide sexual misconduct in Catholic institutions.

F

OOTNOTE

33

Fletcher Harper and his brothers had come of age cringing at what they saw as an immigrant horde invading their city, congregating in filthy neighborhoods, speaking gibberish foreign tongues, practicing their strange “Popish” religion, and corrupting their politics—let alone their rising as a treasonous bloody mob against the draft at the height of their country’s peril during the Civil War.

Nast apparently did not know his Tammany targets personally. At first, he drew his pictures of Tweed and Sweeny from photographs. By one account, he happened to pass Oakey Hall on the street one day about that time and Hall stopped to be polite: “I have not seen your ‘handwriting on the wall’ of late,” the mayor said, referring to a recent Nast cartoon. Nast reputedly looked back without smiling, said “You will see more of it, presently,” and walked on.

34

Once that spring he supposedly passed Tweed as well driving in Central Park; Nast smiled and tipped his hat as Tweed simply nodded and went on.

35

When the three Harper brothers finally met privately at Franklin Square, the conversation apparently turned harsh, the two older brothers, John and Joseph Wesley, arguing loudly against Nast’s anti-Tweed cartoons. Their hard-edged young illustrator was costing them money, they argued, and over what? A campaign heavy on smear and light on evidence? Fletcher Harper listened to the bluster and is credited with a heroically brief response: “Gentlemen, you know where I live. When you are ready to continue the fight against these scoundrels, send for me. Meanwhile, I shall find a way to do it alone.”

36

His stubbornness won the day; his brothers agreed to let him continue. Tom Nast was delighted and responded typically by producing two new cartoons taking the fight to the next level: The first, titled “The New Board of Education,” showed the inside of a city schoolroom under the new regime, with “Brains” Sweeny tossing Harper textbooks out the window, fat diamond-studded Tweed cajoling a student, and Oakey Hall writing the day’s lesson on the chalkboard for the children to master: “Hoffman will be our next president; Sweed is an honest man; Tweeny is an angel; Hall is a friend of the poor.”

37

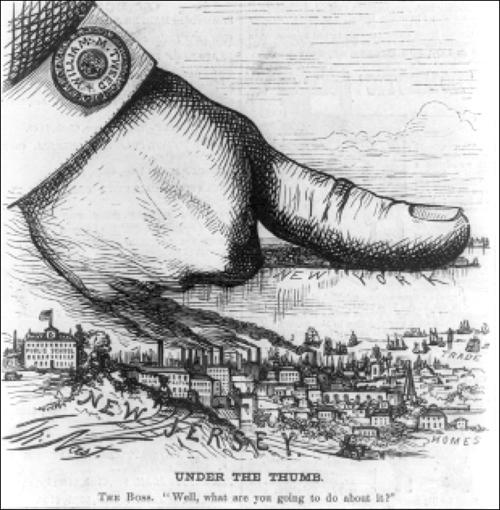

The second cartoon, “Under The Thumb,” published a few weeks later, showed a giant hand placing down its huge thumb over the island of Manhattan, totally smothering the city, as surrounding suburbs remain peacefully undisturbed. A cufflink on its wrist says “William M. Tweed.” The caption reads: “The Boss: ‘Well, what are you going to do about it?”

38

There is no evidence that Tweed ever said these words; Nast apparently made it up. But repeated again and again by Nast, the

New-York Times

, and a chorus of echoes, it became accepted as fact, Tweed’s most famous saying, tarred on him as a rallying point to drive him from power.

F

OOTNOTE

Harper’s Weekly, June 10, 1871.

-------------------------

George Jones made a decision. He refused to yield the

New-York Times

to anyone—certainly not to Tweed and his band—and refused to drop his fight. He had already climbed too far out on this limb. He’d lost dozens of friends, placed his fortune at risk, and subjected himself to insults and intimidation. A stranger had followed him on dark streets for several nights that spring. This most recent threat to steal his newspaper only stiffened his spine. Pride, stubbornness, greed, and duty all pointed him in the same direction, forward.

Jones recognized that until he could purchase a direct controlling interest in the

Times

company and prevent any shares from falling under Tweed’s control, he remained vulnerable. He’d already had one near miss: following a tip, he’d found Tweed’s agents already talking with Henry Raymond’s widow to buy her shares and he’d had to plead urgently to prevent the sale.

39

Now, putting pen to paper in his corner office at the

New-York Times

building, Jones laid out his position bluntly. He probably turned to his editor Jennings to help sharpen his words. First things first, Jones had to settle any doubt that he controlled the newspaper and would not allow any corporate scheme from interfering with his policy. The message had to reach both his own friends, reporters, and shareholders as well as Tweed and the public:

40

“It is my duty to say that the assertion that I ever offered to dispose of my property in The Times to Mr. Sweeny, or anybody connected with him, or that I ever entered into negotiations for that purpose, or am ever likely to do so, directly or indirectly, is a fabrication from beginning to end….

“But, believing that the course which The Times is pursuing is that which the interests of the great body of the public demand, … no money that could be offered should induce me to dispose of a single share of my property to the Tammany faction, or to any man associated with it, or, indeed, to any person or party whatever, until this struggle is fought out. I have the same confidence in the integrity and firmness of my fellow-proprietors….

“Rather than prove false to the public in the present crisis, I would, if necessity by any possibility arose, immediately start another journal to denounce those frauds upon the people, which are so great a scandal to the city, and I should carry with me in this renewal of our present labors the colleagues who have already stood by me through a long and arduous contest.

“I pledge myself to persevere in the present contest, under all and any circumstances that may arise… even though the ‘Ring’ and its friends offered me for my interest in the property as many millions of dollars as they annually plunder from the city funds, it would not change my purpose.”

In an era before newspapers developed the custom of attaching “by-lines” to columns, Jones ended by signing his name. No one must doubt who stood behind this pledge. In the next weeks, little would change at the

New-York Times

; the daily anti-Tammany attacks would continue, though Jennings would use more space to cite the other newspapers supporting the

Times

’ stance. He had to look far for friends: the

Alta California

, the

Boston Advertiser

, the

Cleveland Daily Herald

, the

Indiana Evening News

and, of all the papers in New York City, only one,

Harper’s Weekly

.

One promising sign reached him, though. Jones had heard a rumor: Someone in New York City was shopping secret information about the Ring, financial accounts of some sort. Maybe they’d come to him.