BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (18 page)

Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

“We of New York, those who were born here upon the soil, and those who were not born here but have sworn allegiance to the country, feel that to be respected we must unite [and] as one voice denounce and frown down any attempts at mob violence,” he argued, and saw heads by the hundreds nod in agreement. “We know our rights, we know our power, and we have over ourselves entire control, and hope that no act of violence will mar that day.”

13

The crowd cheered again. They understood the point: Come Election Day, Tammany’s rank and file must do nothing to tarnish victory or give soldiers an excuse to interfere. Instead of the usual ballot box roughhousing, they must show the city their very best manners.

After his speech, Tweed made another gesture. He turned to a former rival standing beside him on the platform—August Belmont, the national party chairman with the thick mutton chop whiskers and former agent of the Rothschild banking firm whom Tweed had attacked just months earlier—and named him the meeting’s honorary chairman. Belmont still privately detested Tweed over the earlier incident; he called Tweed’s crowd “canaille,” French for riffraff from the Italian word for pack of dogs.

14

But he recognized the time to bury the hatchet and graciously accepted Tweed’s peace offer. He avoided mentioning Tweed by name in his speech but did the next best thing: he endorsed Tweed’s vision. “Every Democratic vote… will help towards the election of our Presidential candidate in 1872,” Belmont declared, “and I for one hope to see our ticket then headed by the same name honored today—that of John T. Hoffman.” The square erupted in cheers from thousands of voices.

15

Surprisingly, the night’s most popular speaker was no politician at all but rather Jim Fisk, the pugnacious “Prince Erie” who spent his days manipulating Wall Street and producing operas. “I … have never in my life spoken at a political meeting before, have never voted the Democratic ticket,” Fisk told the crowd, strutting back and forth on the platform. “After to-night there is no question of doubt but that I shall be a Democrat [and] there is no necessity for asking me for my influence with the 25,000 men [Erie Railway employees] under me.” His spunk won the crowd: “I am not afraid of soldiers,” he bellowed. “I don’t think but what, if I find an opportunity, I shall vote three times a day.”

16

On Election Day, Tweed’s army followed orders: They came, voted and kept calm; no violence occurred at the polls. Federal troops and marshals stood sentry but had little to do. Tammany produced a stunning outcome: Oakey Hall won reelection as mayor by 24,645 votes and John Hoffman’s statewide majority for governor topped 52,000—all with few complaints of fraud.

F

OOTNOTE

Hoffman was on his way to the White House and Tammany could boast of facing down Ulysses Grant’s soldiers: The

New York World

congratulated the mayor’s “cool judgment, perfect self-possession, skill, and tact” for winning a “bloodless victory” over the federal army.

17

To the extent the vote had been a referendum on Tweed, he’d won hands down; the

New-York Times

stood repudiated.

Even more important, just before Election Day, John Jacob Astor and his committee had issued their report. They found the city’s finances sound and gave Tweed and Connolly an unqualified clean bill of health: “we … certify the account books of the department are faithfully kept, that we have personally examined the securities of the department and sinking fund and found them correct. We have come to the conclusion and certify that the financial affairs of the city under the charge of the Comptroller are administered in a correct and faithful manner.” Following Connolly’s policies, they said, the city could pay its debts within twelve years.

18

Astor and the others had spent only six hours actually looking at the ledgers and accounts, had seen only material Connolly had shown them, and hadn’t looked behind any of the entries. Still, their blessing cast a shadow far beyond any single Election Day. “These names [Astor and the others] represent the foremost financial interest of their time, and no group of men could have been selected more likely to command the confidence of the people of New York,” conceded even the

New-York Times’

own reporter John Foord.

19

How could anyone credibly accuse Tweed or Connolly of financial foul play after this endorsement? Tammany’s mouthpieces used it immediately to slam critics: a “full and fearless vindication,” the

World

called it. “No one ever questioned that [the books] were [honestly kept] save such unscrupulous and incompetent libelers [sic]” as the

Tribune

, the

New-York Times

, and other “imbecilities.”

20

Critics might shout “whitewash,” but who would believe them? Much later, they’d charge that Astor and his six committeemen had been tricked, threatened, or bribed with tax breaks to issue the report—not likely, given their wealth and experience. Marshall Roberts later would apologize publicly, claiming he’d been manipulated, his certificate “used as a cover and a shield by those who were robbing the city” and took “much blame… for having so readily fallen into the trap.”

21

For now, they’d settled the issue. Connolly and Tweed were honest men.

-------------------------

Jimmy O’Brien had suffered dearly at Tammany Hall for his rebellion. Ever since Tweed had crushed his Young Democrat insurgency in April, O’Brien had been slapped down at every turn: He’d lost his seat on Tammany’s general committee, been excluded from the state convention, and publicly rebuked. Stout, outgoing, with square shoulders, a round, clean-shaven face, dark hair and friendly grin, O’Brien loved a good fight. In September that year, instead of sulking or begging forgiveness, he’d taken another poke at Tammany, publicly throwing his weight behind Thomas Ledbeth, the anti-Tammany candidate running for mayor against Oakey Hall backed by Young Democrats and Republicans, and he invested in an anti-Tammany newspaper called the

Evening Free Press

. Both failed miserably.

O’Brien and Tweed had always liked each other personally. O’Brien as a young Tammany upstart in the mid-1860s had looked up to Tweed, befriended him and called him “Paps.” Tweed, in turn, had backed O’Brien in his bid for sheriff in 1867 despite criticism from older rivals. “Jimmy, I think as much of you as if you were you were one of my own family,” O’Brien recalled Tweed’s telling him once at City Hall, coming up and putting his arm around him at the height of the Young Democrat revolt, offering to make him rich if he dropped the fight.

22

But sentiment carried no weight now; O’Brien had strayed and Tammany had no room for traitors. “We shall cut off their supplies,” one Tweed crony had told the

New York Sun

at the height of the contest. “Thousands of O’Brien roughs now hold sinecures [no-show jobs] in this city. They will never be allowed to draw another cent from the city treasury.”

23

Late that year, Tammany had stripped O’Brien of his nomination for another term as sheriff. Then, when O’Brien had submitted two claims for sheriff’s office expenses, totaling over $350,000—supposedly for “supplies to county jail, carrying prisoners to State Prison and other duties devolving on the sheriff,” separate from O’Brien’s own generous fees—Connolly called them excessive and refused to pay.

24

True or not, fair or not, O’Brien felt the pinch.

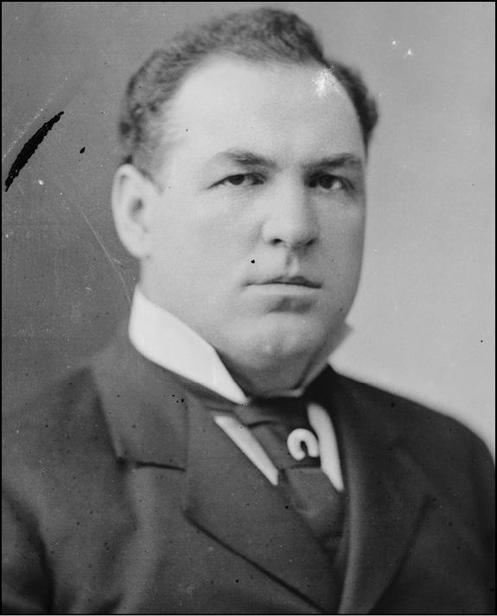

James “Jimmy” O’Brien.

O’Brien had learned politics on the tough streets of the 21st ward (today’s East Side between 26th and 40th Streets): Born in the Irish midlands, his family had settled in New York when he was a child. As a teenager, he’d worked manual jobs. Once, he’d spent two weeks at the Blackwell’s Island prison for participating in a political riot: He was working in a stone-yard on 29th Street and “Our boss was at the time a candidate for some office, and a squad of us went down one evening to attend a primary election in his interest. On our way back there was some little disturbance, and some potatoes thrown, something of that kind,” he explained later, though more likely it was bricks, broken windows and bloodied faces that prompted city prosecutors to put him behind bars. “None of us had any money or friends…. I had nobody to defend me.”

25

Later, O’Brien had shown a charm and political knack; he joined Tammany Hall and, at just 23 years old, he won an alderman’s seat in 1864. He founded a neighborhood club—the Jackson on 32d Street and Second Avenue—and became a local power, the man to see in the 21st ward for political favors. In 1867, Tammany had nominated him for county sheriff, a plum job famous for making men rich, and he won a close race. O’Brien had proved his worth in 1868 by tipping the balance for Tammany on Election Day, ordering his hundreds of deputy sheriffs to arrest Republican voting inspectors and even raiding the lobby of the Congressional investigating committee to bully witnesses.

Now, having rebelled and failed, he needed to mend fences or leave politics forever, and, at 29 years old, he considered himself far too young to end his career. O’Brien used every ounce of his Irish charm to win his way back to the Wigwam. He took his punishment humbly: “I can hardly get a street sweeper appointed now,” he told a reporter asking about patronage.

26

He stood first in line to join the Tweed testimonial association and used Oakey Hall’s annual New Year’s Day reception at City Hall to come and grovel: “You’ve been a kind friend to me, Mr. Hall,” he said, buttonholing the mayor in front of a knot of reporters. “You have never been struck dead for lying; you have never turned one of my friends out of office; you have ever spoken in the highest terms of me behind my back, and slandered me to my face; you have loved me like a brother, and have done everything you could for me.” Oakey Hall loved the oration; by one account, “Tears as big as black walnuts rolled down [the mayor’s] face.”

27

But for burying the hatchet with his former friends, the effort accomplished nothing.

Then one day in mid 1870, Jimmy O’Brien got a break: A neighborhood friend, a fellow named Bill Copeland, came to see him. O’Brien had done a favor for Copeland once and now, Copeland said, perhaps he could return it. Back in January that year, before his rupture with Tweed, O’Brien had used his Tammany pull to win Copeland a city job: Copeland was an accountant by trade, and O’Brien had visited Dick Connolly personally to ask him to hire his friend in the Comptroller’s Office.

F

OOTNOTE

28

“[A] smooth, smiling fellow, bright, clever, and quick,” O’Brien described Copeland.

29

Connolly agreed to take him in; after all, he’d always liked O’Brien—a fellow native Irishmen transplanted in New York City—and sometimes they rubbed elbows together at O’Brien’s haunt, the Jackson Club.

30

Why not do a friend a favor?

All went well at first. Connolly hired Bill Copeland and gave him a desk in the auditing department under bookkeeper Stephen Lynes, an assistant to county auditor James Watson. The Comptroller’s Office was a showpiece: It occupied a large, high-ceilinged chamber on the top floor of the fancy new County Courthouse on Chambers Street. Its interior looked like a bank lobby with marble floors and brass chandeliers, divided by mahogany-and-glass walls into rooms and cubicles with teller windows for clerks to serve merchants doing business with the city. Connolly had given his own son a plum job there as an assistant to city auditor W.A. Herring.

People in the office liked Copeland; they described him as “a seemingly inoffensive fellow and a skilled accountant, who performed his duties… to the satisfaction of his superiors.”

31