Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (20 page)

During the holiday season, Tweed made a show of giving lavish gifts to charity and using friendly newspapers to trumpet his generosity. This year, his bounty overflowed. In December 1870, he gave $1,000 to each of the city’s aldermen to buy coal for poor families in their districts. He listed charities totaling $163,591 that year, a stupendous jump from $3,100 in 1869 and less than a thousand in 1868, and he pressed Tammany to practice the same largesse. In late January, Tammany contributed $15,000 to the Fenians, the radical Irish nationalists whose American followers had launched an abortive raid on British-ruled Canada and whose prisoners had recently been freed from English jails.

56

The prior summer, when drought had caused water levels at the Croton Aqueduct to fall and threaten city supplies, Tweed had paid $25,000 of his own money to buy property adding over 50 million gallons to the system, though he planned to turn a nice profit by selling the property to the city later at good value.

57

He made his most conspicuous gift that year to his old neighborhood: When approached to join a subscription to buy Christmas dinners and winter food for poor families in the 7th Ward—the lower East Side between Grand and Catherine Streets along the East River, the neighborhood where Tweed grew up—he took pen in hand and wrote $5,000 as his contribution. “Oh, Boss, put another naught to it,” an official reputedly joked; Tweed added another digit, making the total $50,000.

58

This time, though, when Tammany trumpeted the story through friendly newspapers, Tweed was startled to find his gesture thrown back in his face—by his tiresome enemy, the

New-York Times

. “Some Stolen Money Returned,” the

Times

headlined, ridiculing it as “Tweed’s Bogus Gift.” “When a man can plunder the public at the rate of $75,000 or $80,000 a day, it does not cost him much to give a few odd thousand dollars to the ‘poor.’”

59

Months after the Astor committee, Tweed saw the

Times

still pummeling him day after day. Though usually he hid the irritation behind his easy-going manner, the constant harping had worn on him. When a

New York Herald

reporter cornered Tweed in Albany at a post-New Year’s reception in January 1871 and asked about the $50,000 donation, Tweed bristled: “That donation, as you call it,… has already given me a good deal of trouble. I don’t want to talk about it at all. I would rather nothing were published about it.”

60

He shifted in his chair as the reporter pressed him on the point, winding his watch chain, crossing his legs, and clearing his throat. “You see, my private affairs of late have kept me a great deal busier than during previous years,” he explained. When the reporter asked Tweed if he’d given the charity simply for “political effect,” Tweed looked at him as though he were either about to laugh in his face or kick him out of the room. “Now, I tell you what it is,” he said, “if I want to spend $50,000 for political capital, I know how to do it as well as the next man. What I don’t know in that way isn’t worth knowing; and you can rest assured that I wouldn’t use $50,000 as a charitable donation if I wanted to make $50,000 worth of political capitol out of it.”

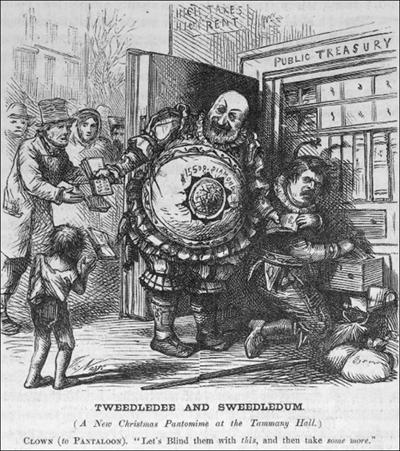

Harper’s Weekly, January 14, 1871.

The newsman scribbled furiously in his notebook as Tweed kept on: “Yes, sir, I have been roughly abused,” he said. “I know that a public man’s lot is a hard one. He’s got to stand abuse; and I am not thin-skinned in the least. I don’t personally care a snap, one way or the other, for either abuse or praise. But when a man is abused even when he is doing what no person of good heart can call a bad act, and he has a family and children he loves, the case is changed entirely. He cares for them, and knows they feel hurt by the abuse which he himself can outlive and outlive happily. But a man’s family is dear to him.”

Tweed finally got up. “A man’s family is dear to him,” he said to himself, and walked away.

61

The next week, Tweed made a decision. He felt abused again, this time by another source: He saw the latest drawing in

Harper’s Weekl

y by Thomas Nast. To Tweed, these Nast cartoons, still barely a handful, had become even more annoying than the

New-York Times

attacks. The latest, called “Tweedledee and Sweedledum,” showed Tweed and Sweeny dressed as clowns named “Clown” and “Pantaloon,” with Tweed’s character wearing a diamond big as a grapefruit lying atop his bulging stomach. The cartoon showed Tweed happily handing out fistfuls of cash from a vault labeled “Public Treasury” to poor men, women, and children while plotting to keep most for himself. “Let’s blind them with this,” Clown (Sweeny) says to Pantaloon (Tweed), cash in hand, “and then take some more.”

Tweed must have noticed how people responded to the cartoon. They laughed—at him! The drawing on its face said nothing. It presented no evidence, no specific charge. It was just an image, a joke, a crude smear, but it made him look ridiculous and weak. How could he answer such a thing?

“That’s the last straw,” Tweed is reported to have snapped on seeing that cartoon in mid-January 1871. “I’ll show those d__d publishers a new trick!”

62

He called together his brain trust. It was time to put the press in its place.

CHAPTER 7

FATE

I

T took William Copeland several months to finish copying the suspicious records he’d seen at his job in the Comptroller’s Office. Coming to work each day at the County Courthouse, walking up the cast-iron stairs beneath the painted ceilings, sometimes passing Dick Connolly, the tall, imposing comptroller himself, in the hallway, he worked secretly. He waited until his supervisors James Watson and Stephen Lynes couldn’t see him. He’d take ledger books down from the shelves and find private corners away from the teller windows or glass dividers to do his pencil work. Finally, by late 1870, Copeland had copied a voluminous treasure trove of information, thousands of ledger entries from the County Liabilities book, each reflecting a city outlay he considered odd. To avoid mistakes, he’d stopped trying to separate suspicious entries and began copying entire pages, ultimately entire books. For each transaction, he recorded the amount, the payee, and the stated purpose. He made no effort to look behind any specific outlay, to confirm its accuracy or legitimacy; he’d taken a big enough risk just in copying the records. The numbers, he hoped, would speak for themselves.

Copeland now took his package—three copies of the hand-written ledgers—and brought them to Jimmy O’Brien, his friend and mentor. O’Brien took them gladly and sent Copeland on his way; whether he paid Copeland money for the job is unclear.

1

O’Brien seemed to recognize fully the import of his new possession; he handled it delicately, like nitroglycerine liable to explode in his hands. He gave it for safe keeping to a city judge, but by January 1871 he’d taken it back. He kept one copy in a safe, the second at his home, and the third with a private secretary. He decided first to use the ledgers to confront Connolly and Tweed over the money they still owed him, the $350,000 in sheriff’s office expenses that O’Brien had claimed in mid-1870 and Connolly had denied him as excessive.

Some time around mid-January 1871, O’Brien prepared a new bill for his $350,000 claim and submitted it to the city Board of Apportionment, a new body created under the 1870 charter consisting of the mayor, Connolly as comptroller, Tweed as director of public works, and Sweeny as parks commissioner—the Tammany Ring in full glory. This time, O’Brien included a note threatening to print certain documents he held if they denied him his money.

Tweed, Sweeny, and Connolly met to talk it over one day

2

and apparently they couldn’t believe O’Brien’s cheek in making the outrageous demand. They started to bicker; the meeting “is said not to have been harmonious,” one reporter heard.

3

First thing, they recognized the obvious; they had a traitor in their camp. Within weeks, Connolly had identified Bill Copeland as the culprit and fired him from his job in the Comptroller’s Office for “political reasons,” as Copeland would put it.

4

As to O’Brien’s direct threat, they split. Tweed and Connolly argued to pay him the money, even though they considered the former sheriff’s claim bogus and exorbitant: “very much in excess of any we paid prior to that time,” Tweed would explain. Tweed had no desire to spark another internal Tammany war like the previous year’s Young Democrat revolt: “I wanted to stop O’Brien’s tongue; he was running around talking.”

5

But Peter Sweeny balked, appalled at the naked blackmail: “Sweeny not unwisely insisted that O’Brien’s greed was insatiable,” journalist Charles Wingate wrote soon after these events, “and [insisted] that an issue might as well be made with him then as at any other time.”

6

They argued, but Sweeny stood firm.

When the meeting broke up, Sweeny and Connolly walked away and left Tweed the job of seeing O’Brien and giving him the bad news. Hoping a personal touch, a cigar and a slap on the back, might smooth things over, Tweed invited O’Brien to his private office at the Public Works Department across the street from City Hall. “Mr. O’Brien wasn’t against me at that time,” he said later. “I was with him, had been his friend in every way, and he professed to be friendly to me.”

7

O’Brien, too, claimed he had nothing against Tweed personally: “Tweed had done me a favor once,” he insisted, “when I was running for sheriff [in 1867, four years earlier] he saved me a great deal of expense and treated me very honorably in certain ways. The inspectors of election were against me, but [Tweed] wouldn’t allow them to cheat me.”

8

But the appeal failed. On hearing he wouldn’t get his money, O’Brien lost his sentimentality, threw a tantrum, and stormed out.

Still hoping to avoid a rift, Tweed insisted that Connolly and Sweeny regroup that same afternoon and reconsider the issue. They haggled it over at length, until after 5 pm that day. Finally, Sweeny relented. They agreed to send James Watson, the county auditor and all-purpose go-between for the Tweed Ring, to go see O’Brien, talk to him, calm him down and maybe reach a deal to buy back his ledgers. Watson, after all, had been Bill Copeland’s supervisor in the Comptroller’s Office; it was his ledgers that had been pilfered. That made it his responsibility. Watson dutifully followed orders and immediately set about to arrange a meeting. He sent messages to O’Brien asking for a time and place. “[Watson] wanted me to take dinner with him and Connolly and Tweed,” O’Brien recalled years later, but he decided to play hard to get. “I refused. But he kept after me.” Soon, they made a date. “He asked me to luncheon one day when we were both on the road,” O’Brien recalled, while they were enjoying their favorite pastime, riding their fast horses through Central Park.

9

-------------------------

James Watson loved horses. When he wasn’t keeping the books or managing financial deals for Tweed and Connolly, he indulged his favorite passion: racing thoroughbreds. Watson’s private stable at 42nd Street just behind his Madison Avenue home housed some of the city’s fastest: “

Charlie Green

,” the quickest, had set a public record of 2 minutes, 31½ seconds per mile; two of his stable mates, “

Fred”

and “

Loleto

,” each had clocked miles under 2:40 and another, “

Dan

,” was acknowledged to have a 2:30 gait but hadn’t been officially timed. “

Loleto”

alone had cost $8,000 when Watson purchased him a year earlier.

10

Watson looked younger than his 45 years and could afford fast horses, along with the stable full of carriages, sleighs, harnesses, saddles, and leather gear that went with them. He’d done well working for Tweed; he’d invested heavily in stocks and real estate and had assembled a portfolio worth almost $600,000.

11

Friends described him as “fully cosmopolitan” despite his Scottish birth and limited education. He belonged to half a dozen clubs including the Blossom, the Jefferson, and the Americus and had raised himself professionally by hard work: Imprisoned in the late 1850s in the Ludlow Street Jail, then the city’s debtor’s prison, for having fled to California with unpaid bills, Watson had earned his freedom by winning the warden’s trust and becoming his jailhouse record-keeper. Afterwards, he’d won a series of jobs from then-sheriff John Kelly and did well enough to be made county auditor by then-comptroller Matthew Brennan in 1863. Since 1866, he’d earned the trust of his newest bosses, Dick Connolly and Tweed.

12

After dining with his wife and two teenage children on Tuesday, January 24, 1871, Watson bundled himself in furs and stepped outside into the crisp, cold air; it was a perfect day for sledding. He hitched his sleigh to two horses and climbed onto the wooden front seat along with his coachman Sylvanus Townsend. He took the reigns himself and snapped the whip; his horses bolted forward, pulling them out onto snow-covered Madison Avenue. They rode north, then turned to the fast roads around Yorkville on Central Park’s east side, thrilling at the speed and wind. They entered the park and followed twisting lanes along steep wooded hills and boulders, occasionally racing other horses, passing shanties where poor families camped by fires, then reached the wild spaces beyond the park and finally the small town of Harlem at the northern edge of Manhattan Island. Here, they stopped the sled, hitched the horses, and stepped into Harry Berthold’s clubhouse for a glass of champagne by the hot fire.

Watson and his coachman didn’t stay long at Berthold’s; night was falling. There was “too rough a crowd upon the road,” Watson later explained, and the road itself had turned rutty. He wanted to travel home in daylight. After a few moments by the fire, he and Townsend bundled up again in their furs and headed back out for the drive south.

They hadn’t gotten far, coming down Harlem Lane with Townsend at the reins, when something happened: Reaching 138th Street, still far above the park, Watson heard a whinny. A horse from the opposite direction had panicked and dashed suddenly across the road, coming directly at them. Townsend yanked hard on the reigns, trying to turn, but the sled’s tracks had gotten stuck in ruts in the snow and wouldn’t budge. The oncoming horse slammed its massive body into the space between Watson’s own two-horse team, breaking the neck-harness holding them together and knocking one horse to the ground. The loose horse reared his legs in the air over the sled’s dashboard. One hoof smashed Watson in the forehead; the other stamped down on the wooden seat sending the coachman, Townsend, flying in the air and crashing down on the frozen street.

Townsend, unharmed, quickly lifted himself from the snow and, looking back, saw Watson lying unconscious on the sled. He raced back to help. Watson soon regained his senses enough to climb down under his own power. Able to walk and having come just a short distance, he had Townsend help him on foot back up the road north to Berthold’s clubhouse. Here they found a police officer named Frazier who dressed the wound on Watson’s forehead and, seeing he was all right, took him home. Police later arrested the driver of the other carriage, a Charles Clifton, but released him after Watson declined to file a formal complaint.

At first, Watson seemed fine. Fully conscious, he was able to walk up the steps to his Madison Avenue home that night and his wound healed nicely the next few days. Then he fell ill, bedridden and feverish. Tweed heard the news in Albany and immediately made plans to return to New York; meanwhile, he sent friends to Watson’s house to help the family and to watch. Doctors soon confessed they could do nothing; just a week after the accident, Watson fell unconscious and died in bed at five o’clock in the morning.

Watson had been a popular fellow. Clerks at the Comptroller’s Office held a vigil and his funeral drew hundreds of friends. The parade from his Madison Avenue home to the 34th Street pier for the ride to Brooklyn’s Cypress Hills Cemetery included dozens of city officials. Tweed, the mayor, Sweeny and Connolly all acted as pall bearers.

Connolly had the strangest response to Watson’s death, seeming both panicked and relieved. Friends saw him dancing at a formal ball that night. Over the next few days, he began shifting people in his office. Watson had handled the Ring’s finances: divided the “percentages,” prepared the bogus paperwork, distributed the money, and kept secrets that could send them all to jail. Could he trust anyone else to do what he did, to know what he knew? Connolly quickly promoted bookkeeper Stephen Lynes to the role of county auditor and, to take Lynes’ spot, he hired a new bookkeeper named Matthew O’Rourke. O’Rourke, a former newsman who wrote on military affairs, seemed trustworthy, but Connolly didn’t rest easy. What exactly he did or how much he actually understood of Watson’s operation isn’t clear, but James Ingeresoll, a city contractor and Tammany Sachem, heard Connolly tell him around this time: “I did a big day’s work yesterday… I got hold of Watson’s book containing the list of payments to us. I tell you, I soon put it out of the way.”

13

-------------------------

Whether James Watson had been

en route

to see Jimmy O’Brien that January afternoon when the panicked horse collided with his sled on the Harlem Road is unclear.

14

What is clear, though, is that he and O’Brien never connected. After Watson died, the former sheriff’s talks with Tweed broke down. His outstanding claim of $350,000 in sheriff’s expenses was never settled.

Instead, weeks passed and Jimmy O’Brien stewed. He puzzled over what to do with the secret ledgers his friend Bill Copeland had copied from the Comptroller’s Office. Should he try again to reach terms with Tweed? Or should he find another use for them, something more dramatic? He hid the books and bided time. When a reporter cornered him in January at a New Year’s reception and asked him about Tammany’s future, he answered with curious fatalism: “[Tammany] is the real power,” he said, pointing to France’s Napoleon III, recently vanquished by Prussian armies under Otto von Bismarck. “However, we cannot tell what a few months may bring forth. No one could foresee the sudden dissolution of the Napoleonic dynasty, which was a greater power, and a few short months since it crumbled into dust.”

15