BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (36 page)

Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

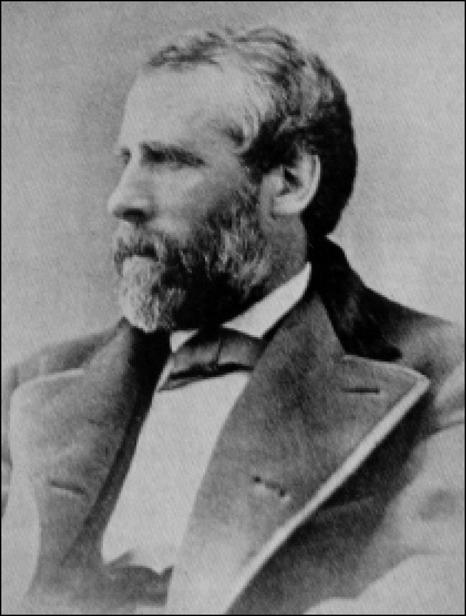

Andrew H. Green.

When Tweed’s circle seized the Central Park Commission in 1870 under the new City Charter and put Peter Sweeny in charge, they’d kept Green as a member but Green effectively withdrew. He boycotted meetings and privately began griping to Tilden and the

New-York Times

that Sweeny’s crooked management threatened to destroy his years of work on the park. For Tilden, Green was one of the handful of friends he’d sought out during August to vent his anger over the Secret Account revelations in the

New-York Times

.

15

By one account, Green had been visiting Tilden at his home on Gramercy Park when Connolly first came to see him.

16

Now, Green had stepped into a hornets’ nest. As comptroller—be it “deputy,” “acting,” “

de facto

,” or otherwise—Andrew Green was responsible for the city’s finances and, as he quickly discovered, he’d been handed a

bankrupt wreck. Green’s clerks counted all the cash in the city vaults over

the weekend and found just $2.5 million. Of this, every penny had to be put aside for the $2.7 million interest payment the city would owe on its mountain of debt in November. Default would cripple credit not just for local governments but for every financial house from Wall Street to Harlem. Beyond that, he had not a cent. Annual property taxes wouldn’t be due for several months and the crisis made normal borrowing from banks and credit markets impossible.

Meanwhile, bills had to be paid and Green had to find the money. Thousands of city employees—laborers, policemen, clerks, schoolteachers, and court-attendants—demanded salaries. Some had gone without pay for weeks and fumed at seeing their families starve. These workers knew how to make trouble; many had blood-stained hands from the July Orange Day riot, the May quarrymen strike, and other brawls. Mobs of hundreds gathered daily at City Hall Park clamoring for pay, mostly peaceful

17

but sometimes turning ugly and having to be chased away by club-wielding police. Green, calm and soft-spoken, often met their leaders and begged for patience but sent them away angry. He had no money.

Sitting at the receiving end, Green had little doubt who was stirring up these protests: Tweed and Sweeny, still sitting like Caliphs over the Public Works and Parks Departments, “inciting the laborers under their orders to make persistent and violent demonstrations,” he wrote. “[The workers] were instructed, day after day, to hang around the finance Department and give the Acting-Comptroller all the annoyance which they possibly could.”

18

Fortunately for Green, the reformers who’d put him in office had big bankrolls and recognized the danger. Heads of the city’s ten largest banks came to see Green that first week and advanced him a rare unsecured loan of $500,000 backed only by Green’s handshake. This money would allow him to avoid immediate bloodshed by paying the workers a few weeks’ salary. In return, Green unveiled a bold reform agenda: He issued orders immediately to forbid political monkey business on city payrolls, asked each office head to produce a list of no-show employees, and began firing them.

F

OOTNOTE

19

At the same time, he threw open all the records in his office to the citizens’ investigating committee, allowing clerks to come and examine them to their hearts’ content.

Richard Connolly, still holding the actual title of “comptroller,” chose to make the best of his awkward situation by becoming “Handy Andy” Green’s best friend. He came to the Courthouse each day and followed Green like a puppy, helping his new deputy learn the ropes and mingle with the staff. They made an odd pair side by side, Connolly tall and boisterous, slapping backs and cracking jokes, Green shorter, serious, and reserved. A newsman described Connolly that week as dressing like a sharper trying to make a good impression: black coat, white silk vest, snuff-colored English broadcloth suit. “His hair was redolent of rich perfume, and his vest glittering with a gold chain,” the reporter noted. “He looked neat and trim, as if he had come out of a bandbox.”

20

During Green’s first day when rumors swept the office about possible violence by police trying to evict them, Connolly had entertained the newspaper writers on his behalf. “They would not be mad enough to do that,” he insisted, but, if violence came, he’d be ready to fight: “They can take me to prison, but I shall go,” he recited dramatically, eyes to the ceiling.

21

To the mayor’s letter declaring that he’d effectively resigned his post by appointing Green his all-powerful deputy, Connolly fired off a sharp reply: “I have not either in fact or equivalent resigned,” it said. “By the appointment of Andrew H. Green Esq., as Deputy Comptroller, I have endeavored to guard the public interest committed to my care.”

22

He sent a courier dashing off to the mayor to deliver it but a messenger brought the letter back a few hours later unopened.

Connolly saw threats everywhere. He refused to step outdoors that week without a bodyguard. He’d burned bridges with powerful people by crossing Boss Tweed and he still labored under a cloud of suspicion from the voucher robbery. New charges surfaced against him that week in the

Evening Post

—doubtless planted by the mayor or Peter Sweeny—that Connolly’s own son J. Townsend had stolen a separate set of county vouchers earlier that year and fled the country with them. Connolly had to find three city officials willing to swear in writing that it had been James Watson, the former auditor killed in the sledding accident the prior January, not Connolly’s son, who’d walked off with the twenty-four missing vouchers representing $3 million worth of city claims—possibly proof of still more frauds—and never returned them despite Connolly’s repeated requests months before Watson’s death.

23

It didn’t stop there. Beyond these public attacks, Connolly heard unnerving rumors that the mayor was planning to have him arrested for forgery. By early October, Connolly found the pressure unbearable. He scribbled out a resignation letter and handed it to Havemeyer—apparently the only person in Gotham he still trusted—but Havemeyer simply put it in his pocket. “I shall not part with your resignation till I secure the appointment of Andrew H. Green as your successor,” he told him.

24

Connolly knew the reformers still considered him a crook even while paying him lip service. Friends speculated he’d stick to his job only so long as Oakey Hall remained mayor. “He has documents that could send Hall and the other fellows to the state prison,” one said, and “wants to get satisfaction of Hall for his treachery.”

25

Capping his nerve-wracking week, Connolly had to wrestle again with his own most recent nightmare: the voucher robbery. That Wednesday night as he was sitting quietly with his wife at their Park Avenue home, a knock on the door interrupted him. It was William Murphy, his night watchman at the Comptroller’s Office. Murphy had brought along a woman named Mary Conway who claimed to know who committed the crime.

Slippery Dick was all ears. He invited them in and heard them out. Mary Conway, it seemed, worked as a live-in maid for Edwin Haggerty, the Courthouse janitor who lived in an apartment in the Courthouse upstairs from the Comptroller’s Office. The night of the robbery, she’d seen Haggerty, his friend Charles Balch, and an unfamiliar man in gray clothes sneaking around Connolly’s office and carrying off loads of papers which they took upstairs to Haggerty’s apartment and burned in the kitchen stove. The smoke had been unbearable, she’d said. She gave a description of the stolen goods—bundles of papers tied with pink ribbons—that fit the vouchers exactly. An inspection later of the ash heap in the apartment confirmed her story. Now, she said, Haggerty had threatened to kill her unless she kept her mouth shut.

Connolly, thrilled at the disclosure, immediately sent for his lawyers, who came rushing to his house that night. They wrote up Mary Conway’s statement in affidavit form, had her sign it, then found a judge to issue arrest warrants for Haggerty, Balch, and Haggerty’s wife. Police found the suspects on the street, took them into custody, and dragged them down to the Tombs prison well past midnight, where a police court judge ordered them held without bail. News of the arrests dominated city gossip for the next few days. Overflow crowds packed the courtroom for Haggerty and Balch’s arraignment to see the two suspects, the maid, and the night watchman testify about the crime—the best entertainment in town. Even Andrew Green took a break from his Comptroller Office headaches and stopped by to enjoy the carnival.

The mystery remained, though. Despite hours of questioning, none of the witnesses shed any light on the crucial point: Who had the robbers worked for? Who had told them to commit the break-in? Haggerty and Balch kept their mouths shut and Mary Conway, the maid, gave the only direct testimony on the point: “Charley Balch done it for me, and I done it for another man,” she quoted Haggerty as telling her.

26

For now at least, though, Connolly could rest easier. Fingers were pointing at somebody other than him.

F

OOTNOTE

27

-------------------------

Tweed spent most of his time after the

coup d’etat

hiding from newspaper reporters in his office at the Public Works Department on Broadway. Here, he greeted the usual stream of politicos hawking gossip and favors but closed the door on newsmen. “I have nothing to say. I cannot say anything,” he told a

New-York Times

writer who managed to grab him in the lobby for a minute. “You can understand my position. I don’t want to complicate my friends.”

28

Behind this stoic front, though, Tweed must have bit back on a stew of emotions that would choke any weaker person: rage, fear, disappointment. That summer and fall, he’d seen a parade of former friends jump ship and betray him: Jimmy O’Brien whom he’d made sheriff, George Barnard whom he’d made judge, and now Slippery Dick Connolly. With Connolly, at least he’d had fair warning. Tweed knew Connolly’s history of treachery: In 1862, when Tweed was still clawing his way up at Tammany and feuding with a rival Wigwam faction, he’d seen Connolly switch sides three times before coming back to ask favors.

29

Now, Tweed must have marveled at Connolly’s gall, trying to cut a deal with prosecutors to save his own fortune while avoiding jail—leaving the Boss holding the bag.

His back to the wall, Tweed spoiled for a fight. His seat in the Albany legislature as state senator came up for re-election that year and, scandal aside, he damned well planned to keep it. The time had come to put his foot down, better late than never. Through his lawyers, he presented his own sworn statement in Judge Barnard’s courtroom that week flatly denying all the charges against him—fraud, conspiracy, misconduct, neglect of duty, or anything else. It was all “untrue,”

30

a “general denial,” he insisted. “I don’t intend at my time of life to go fighting windmills.”

31

The few reporters who did reach him that week found him unapologetic. “As to the cry about thieving—why, that’s politics,” he told one. “I tell you, I shall come out of this fight as clean and square as any man in the community. Only give me the chance to meet the charges openly and aboveboard. I am never so happy as when I am in a fight.”

F

OOTNOTE

32

Tweed still had plenty of friends from his lifetime of favors and spoils. “All my professional and personal ability or influence is at your service at all times and upon all occasions,” James C. Spencer of the State Supreme Court wrote him.

33

Leaders of the William M. Tweed Association of the Second Ward (today’s lower East Side around Fulton Street) cheered him at a rally on Park Row that week and blasted his opponents as “a few political soreheads and vile ingrates.”

34

Other friends formed a new Central Tweed Organization to back his re-election to the state senate.

35

Even Jimmy O’Brien, who’d brought disaster on Tweed’s head by disclosing the Secret Accounts to the

New-York Times

, still spoke fondly. “Mr. Tweed is the most honorable man of the lot,” he said when asked about the jousting at City Hall: “Tweed is plucky…. He knows what he is about, and they can’t play any of their games on him.”

36