Bradley, Marion Zimmer - Novel 19 (37 page)

Read Bradley, Marion Zimmer - Novel 19 Online

Authors: The Ruins of Isis (v2.1)

"I

hope you have recovered," Miranda said, with kind anxiety, "but they

seemed to feel it concerned you in some way; a man, a messenger, came to

Vaniya. She would have sent it away, saying this was not the hour for receiving

petitions, but it insisted almost with rudeness, and spoke with her for a long

time, insisting that the women of the household go out of earshot. My mother

even sent Rhu away—but when the man was done speaking, she called out in great

anger for her guards, and sent the man to the Punishment House. And after, she

told Lialla to say nothing of this to the Scholar Dame, since she did not want

you worried by trifles. Cendri—I had a strange feeling it might have been

something to do with Dai's disappearance. My mother does not know—" she

laid her hand over Cendri's, "that your Companion is your life-partner as

well, and such a thought would never enter her mind. But I know a little, I

think, of what

your—

your Companion means to you, and I

think you have a right to know, if this man truly brought a message concerning

him."

This

seemed to confirm Cendri's worst fears. She said, shakily, "I must speak

with the messenger, Miranda. Where is he?"

"In

the Punishment House, Cendri, and I fear it was beaten. No," she added

quickly, "you cannot go to the Punishment House alone, no woman may except

Vaniya's appointed guards, and I do not think they would give you, alone,

access to the prisoner; but I will go with you."

Cendri

was grateful, but still felt some compunction. "Oh. Miranda, you are ill,

suppose you go into labor—"

"Believe

me," Miranda said, with heartfelt sincerity, "nothing on this world

could please me more! If it has that effect, I shall bless the effort I

make!" The midwife returned with Miranda's drink; she motioned it away.

"I

will walk a little with my friend, the Scholar Dame from University—" she

silenced the woman's protest, saying gaily, "You have been telling me for

three days that I should bestir myself and take exercise, and now when I am

willing, you would prevent me! Cendri will make certain I do not fall on the

stairs, will you not, my friend?"

Cendri

supported Miranda carefully on the long flight of steps, feeling intensely

protective.

Isis

has changed me in one

way,

she

realized; my relationships with women will never again be quite

the

same.

The awareness that she could actually relate to another woman as to a lover,

she knew, was going to make some permanent difference in her self-image, but

she was not yet sure what form it would take. At the moment, she realized, she

felt as close to Miranda as if the woman were her own sister.

It

seemed for a moment that Miranda was reading her thoughts when she said,

"So now you have visited the sea with us—tell me, Cendri, what

do you

think of our festival?"

Cendri

said honestly, "I don't know yet what I think; I was surprised and—and a

little confused. And I suppose, then, there will be an enormous number of

births two hundred and eighty days or so from now?"

Miranda

shook her head. "No, not really; that will be an unpleasant time to bear a

child, in the worst of the summer heat. Most women who want children arrange

it, as I did, to try and become pregnant at winter-festival, so that the

children will be born at this season of the Long Year, and some others, women

who work on farms, try to conceive at the harvest so that their children will

be born before sowing-time. Although there are always some women so eager for

children that they do not care when they conceive—my sister Lialla, who seems

barren, though she has gone unprotected to every festival for years now.

Cendri!"

She looked at her in dismay. "Do your

women in the maleworlds have no way to avoid conception except to keep apart

from men? One of us should have warned you, told you—did you expose yourself,

unprotected, to the sea-coming? It can still be remedied, but the process is—is

unpleasant—"

Her

concern was so sincere, so contrite, that Cendri quickly hugged her as she

reassured, "No, no, we have such ways, I am in no danger of pregnancy,

whatever I should do, but I was not sure your people did—"

Miranda

laughed. "Believe me, it was the first thing to which the Matriarchate

gave priority in research! Not many women wish for more than two or three

children, if so many, and there are some who wish for none at all, although I

must say that seems strange to me— if I could not bear children, I think I

would almost as soon have been born male! But then there are also some women

who wish for children eagerly, and no sooner wean one child from their breasts

than they are eager for another, and of course we are all grateful to them. But

did it seem to you that our festival had no meaning but that, Cendri, for the

giving of children?" She looked up anxiously at Cendri, and Cendri said,

"I have not been among you long enough to know what meaning it might

have."

Miranda

said slowly, "One of our priestesses could explain it to you better than

I. These festivals—Three times in our Long Year we visit the sea; it is our way

of remembering, of commemorating that both men and women are the children of

the Goddess, whom once we named Persephone and here we call Isis, that all of

life including our own comes from the sea; that men, too, have their needs and

goals and desires, and that we must join to give them what they need, too, and

keep them happy and contented." And now Cendri was more confused than

ever, but Miranda did not explain further.

"Here

is the Punishment House; I, as Vaniya's heir, have authority to admit you

here."

She

spoke briefly with the hefty, sun-tanned woman at the doorway, and the woman

went away, letting Cendri and Miranda inside.

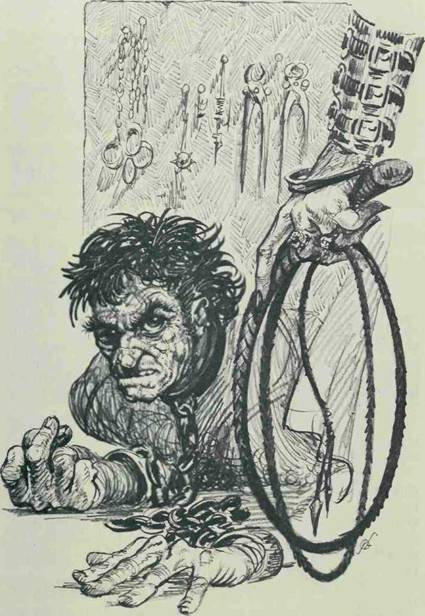

In

the course of her studies Cendri had visited many places of confinement on many

different worlds; the Punishment House of the Residence of the Pro-Matriarch contained

four identical small barred rooms, cells, weathertight and immaculately

clean

. The inhabitants—there were two at present—looked

clean and well-fed, warmly clad against the chill and provided with blankets;

nevertheless Cendri shrank in distaste from the display, on the wall where

every inhabitant of the Punishment House could see them, of a variety of

increasingly unpleasant instruments of restraint or punishment, including a

variety of long, brutal whips. She also remembered what she had been told upon

first landing on

Isis

; the penalty for any male who attacked a

citizen was immediate death, meaning that males being punished could not even

resist without incurring immediate destruction like any wild or dangerous

animal. She shuddered in horror, thinking of Dal in such a place as this.

Miranda

pressed her hand. She whispered, "I know, I feel that way too. It is

horrible. And yet most males cannot be controlled any other way; you cannot

judge them all by the kind of men whom we know; they are exceptional, you

know."

Cendri thought of the boy who had

wept in her arms at the seaside, of the gentleness of every man there, of the

genuineness of the communication. Not for sex alone, but for some kind of

togetherness, some way of re-uniting the sundered halves of the society—she

found herself wanting to cry, because even Miranda did not understand.

Miranda

said, gesturing, "This is the messenger. He was interrogated by the lash;

but Lialla told me he said nothing and at last they were convinced he knew

nothing worth telling, more than was in his message. But you should ask him

about it, since the message—the message Vaniya did not give him leave to

deliver—was for you. Yal," she said, to the man who lay huddled on the

bare floor, shivering under his blankets, "I have brought the Scholar Dame

from University to you. If your message concerns her, you are now free to give

it."

The

man Yal slowly, dragged himself upright. Cendri saw with horror that the back

of his thick coarse shirt was flecked with blood, and that he moved as if every

motion cost him excruciating pain.

He

said, "You are indeed the Scholar Dame from University? The Mother Vaniya

said that you would have no interest in the message I bear—she said, what is a

male to the Scholar Dame?"

Cendri

said quietly, "Vaniya was mistaken, Yal. If you bear a message from my

beloved Companion, let me hear it."

"Respect,

Scholar Dame, the message is not from your Companion, but concerning him,"

Yal said. "I was to say that your Companion, the Master Scholar Dallard

Malocq, is being held in the work-settlement of the men at the great dam, and

that there he will remain until men of the Unity are sent here, to learn of the

conditions under which men of Isis must live and suffer all their lives without

freedom. We demand that the Unity shall require the women of

Isis

to grant us the rights of free citizens,

and until the Unity has answered us we shall hold the worthy Scholar Male among

us."

Cendri

gasped. So this was the end of Dai's work among the men of

Isis

—to be held as their prisoner, to force

action from Vaniya!

It

might have worked, with Mahala

..

.she wants

Isis

a part of the Unity, but on

their own

terms. But Vaniya! Cendri's blood ran cold. Dearly

as she had come to love the Pro-Matriarch, she knew that the woman would never

compromise with the men.

Miranda

said sharply, "That is not the way things are done on Isis, Yal. I can

assure you, as daughter of the Pro-Matriarch, that if you return the Scholar

Dame's Companion to us, and return to your duties, my mother Vaniya will be

ready and more than ready to listen to any reasonable request."

Yal

said, "We have done with reasonable requests, Lady; all reason has done

for us is to keep every male on

Isis

in chains."

Cendri

begged, "Where is my—where is the Master Scholar from the Unity being

held?"

Yal's

bruised face moved in a smile. His lips were swollen and darkened with dried

blood. He said, "Ah, Respected Dame, that would be telling, now, wouldn't

it? And you can see they asked me, and they knew how to persuade me; if I'd

known—" he shuddered, "I'd surely have told, wouldn't I? I told them

before they sent me, don't tell me anything. What I don't know, they can't make

me tell, see, not even if they kill me."

Cendri

shuddered; he spoke so matter-of-factly of torture and death. Was this what Dal

would suffer for the fate of their messenger? This brave, and stupid, volunteer

would die for his cause; but would it do him any good?

Miranda

said sharply, "Is it worth it to you to be beaten and tortured for this

folly, man?"

Yal

smiled again. His smile, in his tortured face, was very terrible. He said,

"But there are not enough women on

Isis

to beat us all to death one by one,

woman." He used, not the term of respect, but the simple female noun.

"I came here knowing I would be questioned as all men are questioned, by

the whip, and then put in chains, as all men on

Isis

live chained by the will of women.

But—" he held out his right hand; made the slow unloosing gesture Cendri

had seen before, "we were not born in chains! And we will not die in

them!"