Breaktime (16 page)

Authors: Aidan Chambers

After Helen

WHEN I WOKE,

the sun was setting. Egg yolk in deepening blue.

My sleeping bag covered me. Helen’s doing, I supposed.

I looked for her. Found not her, but her note lying by my side weighted by a dalestone.

I read it.

Then lay back. Wordless thought.

Then, impulse:

I had to go back home. Whatever I had come for, I now had. But had yet to sort out.

I felt good as soon as I moved, being busy again with purpose. Whatever I am to be, I am not to be a drifter, a taker-or-leaver of life. I know that now, if no more.

I ate the remains of our lunch, being hungry: stale bread, evening dew moist; a mouthful of herring, acid in my dry sleep mouth; a morsel of cheese; all washed down with water, plastic coated from my aging bottle. Then sat again, feeling calmed, reflective; gazed at the view as though wishing to cherish it, the day, that time-and-place.

Till darkness fell. Ten thirty or thereabouts.

I was ready for off. I would have to walk. No buses now, no money for private hire. Fifteen miles. But I wanted to walk.

Penance, payment or pleasure? Who cares?

I was going somewhere. Home.

The only one I have. For now.

I laughed.

An owl hooted. A barn owl. He was sitting on Willance’s cold grave stone. As I watched, he took off and ghosted into the valley.

Tramping

Down into Richmond, silent dark town, through Skeeby. On up to Scotch Corner, across the slice of motorway and along the back road to Barton. Then Stapleton and the roundabout, junction of old road and motorway spur into Darlington. Across the bridge humping Yorkshire into County Durham. Then by Blackwell down to South Park, along Geneva Road’s dull, stale mile. And home.

Roadwork at night is a kind of torture by monotony. Thoughts adopt a steady repetitive stomp to match your mechanical feet.

My thoughts that night tramped through Jacky and Robby and Helen and me.

Pedestrian stuff; all here, preceding.

Home

Hello, love

.

Hi, Ma. Didn’t mean to wake you.

I wasn’t asleep. How’ve you got back?

Walked.

Walked? Where from?

Richmond.

At this time of night! It’s nearly four

.

I’d finished what I had to do so I came straight home.

I’m glad. But you must be worn out

.

A bit.

And hungry. I’ll cook you something

.

No, no, Ma. Just a cup of tea, eh?

Are you sure? You ought to have something

.

I’m okay, really.

Well, a cup of tea, eh?

How’s Dad?

Much better

.

Good.

Not right yet, you know. Never will be, I suppose. But he’s sitting up and taking notice again

.

That’s good.

Thought I’d lost him

.

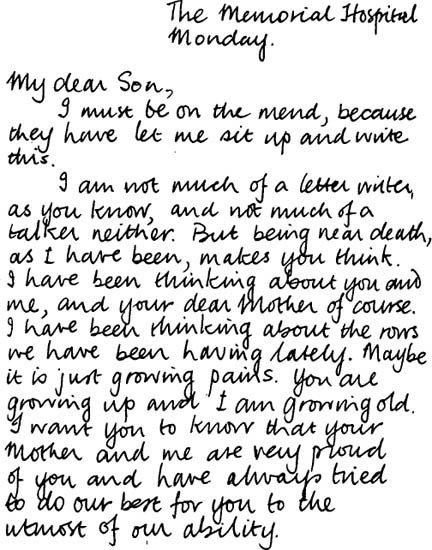

O, I’ve a letter he gave me for you

.

A letter?

Wrote it yesterday. Said if you rang I was to get an address where you could collect it. If you weren’t coming back soon, like

.

He’s never written me a letter before.

He’s hardly had need to, has he? You’ve not been away long before, not on your own

.

But he didn’t need to now, did he?

What’s in it?

I don’t know, love. You’d better read it and find out

.

I’ll take my tea and drink it upstairs, Ma. Okay?

All right, love. And get some sleep. You’ll be worn out tomorrow

.

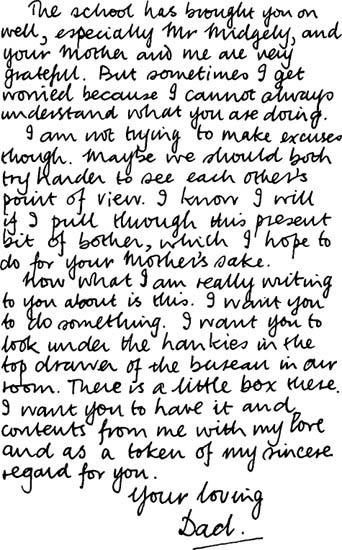

Free Gift

A small, black, firm-bodied box, no bigger than a wallet, edges worn, as though from much handling. Inside, red silk plush. Laid in the plush, two medals, pristine, with bright red, gold and blue striped ribbons. On the medals, raised in bas relief, the picture of a racing motorcyclist. On the reverse an inscription:

NATIONAL TRIALS CHAMPIONSHIP

JUNIOR CLASS

FIRST

NATIONAL TRIALS CHAMPIONSHIP

ALL COMERS CLASS

THIRD

Each also inscribed with Dad’s name and a date.

He would have been eighteen.

Kitchentalk

You’re still up, Ma.

I’m not tired, love

.

He’s given me these.

Yes? Very nice

.

Why?

He wanted to, I expect

.

They mean a lot to him?

They do

.

He’s never mentioned them. I’ve never seen them before.

It’s just the way he is

.

You know about them?

Yes

.

Can you tell me?

When he was young, he wanted to be a motorcycle racer. He went to the Isle of Man T.T. races every year to watch. ’Course, then it was bigger than it is now. I’m talking about thirty years ago. He got a bike of his own as soon as he could. Bullied his mother into buying him one on the H.P., I think. And he started trials racing on it

.

Racing across country?

Yes. He did well. Won them medals the last time he did it. He was eighteen. He decided after that it was time for the real thing. But he needed a new bike for professional stuff. And he wanted to enter the T. T. Something like that

.

And?

His father wouldn’t hear of it. Put a stop to it

.

Why?

Said it was too dangerous and cost too much

.

But how could he stop Dad if he really wanted to do it?

Well, for a start your dad didn’t have the money. Not for a new bike, fares, racing expenses, all that

.

And his father wouldn’t help?

No

.

Wasn’t Dad earning enough?

As an apprentice joiner? That’s what he was then

.

So he never did it?

No. His father said he could do what he liked when he was out of his apprenticeship at twenty-one but that till then he’d do as he was told. And in those days you had to pay more heed to your parents than people do now

.

But didn’t he try when he was twenty-one?

Too late then. He meant to. But he’d never have caught the competition by then. And anyhow, how could he do it all on a joiner’s pay? No, he had an old bike and roared round the streets like a madman and went to the T.T. as a spectator. But he never raced again

.

Does he regret it?

Why don’t you ask him?

Silly question.

Perhaps. But I’d still ask him

.

Thanks, Ma.

Get some sleep now, love. Goodnight

.

Making Room

I sat a while in my room. Needing to. Not disturbed, but wanting quiet. Peace. Stillness.

But soon the walls were falling on me.

Unhurried, a deliberate act conducted with great care, I began to disrobe the walls of their covering of posters and pictures. Took them all down; piled them one on another in an old suitcase.

Did not stop at the pictures. The ornaments, bric-à-brac, oddments of all sorts. All the left-overs of me. All into the suitcase.

With surprise I found myself adding some of the books. Not all. Those which impulse told me were sloughed-off skins.

Me, past. Other people’s me.

Last of all, I placed Helen’s letter, her photograph, and Morgan’s

Charges Against Literature

into a large envelope. Sealed it. Placed it on top of all else.

Shut the suitcase. Locked it. Stowed it neatly, at the back of a cupboard in the spare bedroom, among all the rest of the family’s lumber.

Put the key into my father’s medal case beside his—my—pristine medals.

Now my room was nude, but for some books, and, alone on my desk, the medals in their worn case.

Coffeetalk

‘An odd concoction,’ said Morgan, coffee expectorating from his plastic mug on to the sixth-form commonroom floor as he and Ditto made for two empty seats in a corner.

‘We have discussed the inadequacy of the coffee before,’ said Ditto.

‘I mean your masterwork,’ Morgan said.

They sat, pulling their chairs together, side by side, facing a window providing a view of the breaktime mayhem in the playground below.

‘Did you find it distasteful?’ asked Ditto.

‘Not that. But there are some points I want to argue with you.’

‘What then?’

‘Amusing sometimes, embarrassing sometimes, interesting sometimes.’

‘How generous of you.’

‘You had quite a time during half term.’

‘I did,’ said Ditto noncommittally.

‘But to be honest . . .’

‘Why not?’

‘. . . I can’t agree that this curious document answers my Charges.’

‘You disappoint me, Morgan.’

‘Then demonstrate.’

‘What a laboratory mind you do have.’

Morgan smiled with self-satisfaction.

‘All right,’ said Ditto. ‘Point by point but briefly. Point one: is it a story?’

‘Of a kind,’ Morgan conceded with reluctance. ‘The events of your week past.’ He chortled at his pun.

Ditto allowed the ambiguity to pass apparently unnoticed. Two could play at double takes, and at sleight of mind.

‘Point two: you are only concerned with truth. Have you had truth?’

‘Allowing for the inadequacy of your skills as a reporter, yes.’

‘My modest work convinced you in this respect?’

‘Sufficiently for our purpose.’

‘Good. Point three: would you agree that my account does not pretend that life is neat, tidy, falsely logical—any of those things to which you objected, you’ll remember?’

‘Granted. It’s a right rag-bag!’ Morgan laughed loudly.

‘I’m pleased I amuse you.’

‘You do, you do.’

‘Point four: literature is only a game, an amusing pretence, a lie I think you said. Playing at life, wasn’t it?’

‘Correct.’

‘Is my poor effort?’

Morgan sat up, as though springing a trap. ‘I thought that was where you were headed. False logic.’

‘Why?’

‘Because, matey, I was talking about fiction. Remember! And your little masterwork isn’t fiction.’

‘O?’ said Ditto.

The klaxon sounded the end of morning break.

‘Of course it isn’t,’ bayed Morgan, triumphant. ‘We’ve already agreed about that. It is a record of what happened to you last week.’

‘That’s what

you

said. I only asked if it convinced you in that respect. You said yes.’

‘Are you playing games?’

‘Do you mean, have I written fiction?’

‘Declare!’

‘Could be. How do you know I didn’t sit in my room at home all week making the stuff up?’

‘I don’t believe you.’

‘Thank you. That’s the best compliment you could pay me.’

‘But your father is ill, you’re not lying about that, are you?’

‘Of course not . . .’

‘Well then . . .’

‘All fiction starts from something.’

‘Look, I’ve got Taylor now. He brooks no lateness. We’ll settle this over lunch.’

‘A viva I shall enjoy.’

Morgan made for the door.

‘I’m in the thing,’ he said as he went. ‘Are you saying I’m just a character in a story?’

‘Aren’t we all?’ said Ditto and laughed.

About the Author

Aidan Chambers lives in Gloucestershire with his American wife Nancy. He has received international acclaim for his provocative and challenging novels for teenagers and young adults. Among many prizes, he has won the Carnegie Medal and the American Printz Award for

Postcards from No Man’s Land

and the Hans Christian Medal for the body of his work. His books are translated into many languages and he travels extensively on speaking engagements. He is a playwright and an anthologist and also writes stories for younger children. In 1982 Aidan and Nancy were given the prestigious Eleanor Farjeon Award for their work on behalf of children’s books.