Breasts (11 page)

Authors: Florence Williams

Tags: #Life science, women's studies, health, women's health, environmental science

She’d no doubt be discouraged by the extent to which chemicals are even more embedded in our food systems and personal lives than they were fifty years ago. But she’d be fascinated by our increased understanding of how they affect so many bodily processes.

Eighteen months after

Silent Spring

was published, Carson was dead at age fifty-six. She had breast cancer.

SHAMPOO, MACARONI,

AND THE AMERICAN GIRL:

SPRING COMES EARLY

Still she went on growing, and, as a last resource, she put one arm out of the window, and one foot up the chimney, and said to herself, “Now I can do no more, whatever happens. What will become of me?”

— LEWIS CARROLL,

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

O

N THE AFTERNOON SONYA LUNDER CAME TO VISIT, I

was, as usual, madly making after-school snacks for the kids, who are seven and nine. It entailed scooping some dip out of a store-bought plastic container, peeling carrots, and slicing some cheese. The kitchen is where love and guilt—those dual sirens of parenthood—merge at their most intense. It was a fitting place to begin planning a chemical-body-burden experiment. At the heart of the experiment lies one central fact: girls today are getting breasts earlier than ever before.

Lunder works as a senior toxins analyst for the Environmental Working Group. The mother of two small children, she has taken

her knowledge of chemicals into realms I never imagined. At the gym where our kids take classes, she noticed the big foam blocks in the “pit” that students land in as they jump off a rope swing. She asked the gymnastics director if the foam was treated with flameretardant chemicals, which are known to slough off and accumulate in human tissues. To his credit, he’d actually considered the question before and told her he tries to get untreated foam. She encouraged him in her friendly Sonya way to keep trying.

In my kitchen, Lunder zeroed right in on the fridge. Even the door’s water dispenser attracted her attention. “You know, the water tubing is probably plastic,” she said. After noting all the plastic-contained food in my fridge—yogurt, juice, cheese, meats—she pointed to a cutting board on the counter. She asked if the original packaging had said “antimicrobial” on it. I shrugged. “If it did, that means it’s embedded with triclosan,” she said. She scrutinized my hand soap gel. I thought she’d be happy, because it was from a leading “green” brand and declared on the bottle that it contained no parabens. “Interesting!” she said, reading the smaller print. “It’s got benzophenone in it! That’s related to a sunscreen chemical linked to endocrine disruption in animals. Why would they put that in your hand soap?” she mused. “It probably keeps the contents from breaking down in UV light.”

Lunder was here to help me prepare for the detox phase of my home experiment, in which I would valiantly try to avoid exposures to chemicals to see if I could reduce my body’s levels of toxins. The experiment, designed with help from both Lunder and Ruthann Rudel, the toxicologist for the Silent Spring Institute, would incorporate a before and an after phase for both me and my seven-yearold daughter, Annabel. We would compare our levels to those of five other American families in a study sponsored by Silent Spring and the Breast Cancer Fund, both nonprofits interested in elucidating

the environmental connections to breast cancer. In the first “tox” phase, Annabel and I would live our normal lives, absorbing hidden molecules of plastic from our food and the occasional canned beverage, as well as from shampoo and moisturizers purchased from the supermarket. In other words, for three days, we would be average Americans. Then we would pee into some glass jars and ship them to Canada for testing. A week later, I would enter detox for three days. I would become a vegan, avoid triclosan and plasticizers to the best of my ability, and have my urine retested. I would not drive (to avoid chemicals in the car upholstery and interior) and would only eat food that had never touched plastic. As a testament to just how foreign this is to the American experience, I couldn’t imagine getting Annabel to undergo full detox. It would mean no vehicles, no pizza, no bubble bath. I didn’t have the heart to put her through it. For much of phase two, I’d be on my own.

WHY BOTHER WITH ALL THIS? BLAME IT ON THE GOVERNMENT.

For seven years, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and the National Cancer Institute have joined forces in a $40 million study trying to understand the forces behind early puberty and its link to breast cancer. I’d heard about the effort, called the Breast Cancer and Environment Research Centers (BCERC), and was closely following the results, which fall into three main buckets: chemical exposures, lifestyle (diet and exercise), and social factors (economic status, number of parents in the home, etc.). Data have been coming out of four research hubs across the country, in which a total of 1,500 girls were participating, beginning at the age of six. Already the information shows these girls have some of the highest body burdens of everyday chemicals yet seen.

As a group, they also have the youngest breasts ever recorded. I was curious to know how our levels matched up, and what it all meant.

Scientists have known about the relationship between the age of puberty and breast cancer for a long time, ever since they began looking at lifetime estrogen exposures. Then in 1997, Marcia Herman-Giddens, a scientist at the University of North Carolina, published a bombshell of a paper. Her research indicated that girls were developing breasts and sprouting pubic hair one to two years younger than expected, with white girls getting breasts at a mean age of 9.8 years and black girls at 8.8 years (menstruation typically starts two to three years later). Within two years, experts revised the official definition of “precocious puberty” downward, from age eight to seven in white girls and from age seven to six in black girls. Welcome to the new normal.

The age of puberty matters. A 2007 report for the Breast Cancer Fund notes that if puberty can be delayed by one year in girls, thousands of breast cancers could be prevented. Suzanne Fenton, a scientist with the Reproductive Endocrinology Group at NIEHS, went even further. “We think that puberty may be the main driver in the risk of breast cancer,” she told me. If you get your first period before age twelve, your risk of breast cancer is 50 percent higher than if you get it at age sixteen.

Why? It might have to do with hormones. Earlier puberty means an additional few years of estrogen and progesterone flooding the breasts and causing cellular changes. Or it could be that estrogen gets metabolized by the body into some toxic by-products that create free oxygen electrons and can damage DNA. But why would an extra year or two have such a big effect given our long lifetime of ovulating? Another theory is that puberty—with all its inherent cellular instability—causes breasts to be extra vulnerable to

carcinogens. If puberty comes earlier, that window of vulnerability is open for longer. The new government-funded research attempts to answer some basic questions: What causes early puberty? Is it something we can possibly manipulate?

I got my first period when I was eleven. Annabel is likely to fall on the early side too, since the magic number is driven partly by genes. At seven, she is the perfect age to examine suspected environmental factors. We’re testing for some of the same chemical candidates investigated in the BCERC study: BPA, phthalates, triclosan, parabens, and flame-retardants, all common substances known to mimic sex hormones or otherwise interfere with their normal coursings through the body.

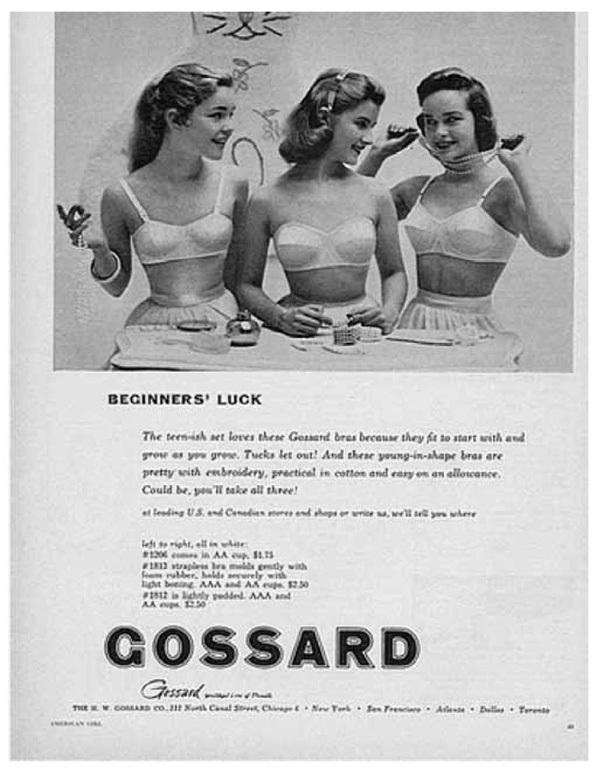

When I look at Annabel, I see total prepubescence. She sings and twirls around and makes elaborate rooms and nests for her dolls and stuffed animals. She is still drawing figures that are not anatomically endowed. It’s almost inconceivable to imagine that some girls her age are actually wearing bras. To put the data into perspective: by 2011, one-third of black girls between the ages of six and eight were “budding” breasts (that’s actually the technical term) or growing pubic hair, along with 15 percent of Hispanic girls, 10 percent of white girls, and 4 percent of Asian girls. Some of the breast budding is correlated with obesity. We live in the thinnest town in America—Boulder, Colorado—and not many of the mostly white, professional-class kids in Annabel’s elementary school are overweight. Still, the fourth- and fifth-graders are maturing here earlier than they did when I was their age. Today, half of all girls in the United States start popping breasts by their tenth birthday, well ahead of girls of the

Brady Bunch

era.

If you’re a parent, this should make you nervous. Puberty has got to be one of the strangest and most profound experiences we

humans undergo. Breasts and hair appear out of nowhere, voices drop, personalities change. We get hijacked by hormones and taken to another planet. It would all be comical if it didn’t involve teenagers doing so many stupid and hazardous things involving their bodies, high-speed vehicles, and illicit substances, sometimes all at the same time. Girls’ bodies begin to enter an uneasy and public arena of male attention. We probably all remember that exquisite tension between wanting to show off our new breasts and not wanting anyone creepy to notice them.

I started getting breasts around the summer between fifth and sixth grade. That’s when my father gave me a book about girl power. His girlfriend, a librarian, had recommended it. The gist of it was how to say no to boys or men who wanted you to do things you didn’t want to do. I was uncomfortable reading it. I was uncomfortable discussing it with him. I just wanted to think about my new blue Princess phone and calling my girlfriends.

By the next summer, when I was twelve, I had small but shapely little mounds. I was now tall enough to wear some of my mother’s clothes, a rite of passage in itself. She had a designer T-shirt, an incredibly soft, thin weave in orange and green stripes. It must have shrunk in the wash because I don’t think it could have fit both of us. She was a 36D, and I was probably a 28AA. But the shirt fit me, and I claimed it. It was a treasure. Between the thin cotton and the stripes, I knew it made the most of what I had.

That summer I traveled out West with my father and some family friends, including two teenaged boys. I wore the shirt often. One day we hired a guide and some horses and rode out to see some ancient ruins in the Arizona desert. It was a long ride over rough country. On a couple of occasions my horse lagged behind and out of sight of the others. Our guide, a youngish Navajo cowboy, would

come galloping back to me, reach out, and give my nearest breast a squeeze. He would roar with laughter and try to do it again. I rued my slow horse, my striped shirt, and my posse for leaving me behind. I goaded that old horse until I finally caught up with the others.

A few months later, in the completely different canyons of New York City, I took a taxi with two friends across town. After we paid our fare, the driver reached back through the open Plexiglas window and groped us as we slid across the seat to the door. That time I cursed him out and slammed the door. Maybe my father’s assertiveness training had gotten through. I was now in the brave new world of boobs.

How many girls have memories like this, or worse? Probably all of us.

It’s hard enough to stand your ground as a preteen. But an eight-year-old is pretty much incapable of it. Little girls aren’t emotionally equipped to handle the challenges of puberty. Teens barely are. Girls with breasts are the targets of teasing and jokes by their peers, and statistically they’re more likely to be victims of sexual assault. Studies have shown that prematurely developed girls are at greater risk of substance abuse, depression, and suicide.

Lately, the advent of earlier puberty has converged with the advent of 3G and 4G video-phone technology. The tragic result, according to pediatrician Sharon Cooper of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine: more cyber-sexual exploitation of very young girls.

WHILE THE DECLINING AGE OF SEXUAL MATURITY IS WORRISOME,

it’s important to know that it’s not entirely new. Here’s the general evolutionary scenario: if you can eat more, you can reproduce earlier, resulting in more offspring. And in fact, our ascent out of caves and

hovels has meant that the age of sexual maturity in girls has dropped slowly but steadily, about three months per decade, since 1850. The reasons for the change were expected and benevolent: better nutrition and less infectious disease. But does this mean that we’re designed by nature to have babies as early as we possibly can? Not necessarily.

Humans, as we’ve seen, are unusual creatures. One of the ways in which we are unique lies in our prolonged childhood. We take longer to reach sexual maturity than any other primate, meaning we sit around for more time being relatively useless with regard to the propagation of our species. (Chimps, by contrast, become mothers when they’re six to nine years old.) There are good reasons for our dawdling; namely, our bodies and brains are big and grow slowly. The longer we hold off puberty, the taller and stronger we’ll be and the greater the likelihood our offspring will be healthy too. (One of the reasons boys grow taller than girls is that they reach puberty later. The sex hormones that come with puberty, such as estrogen in girls, actually seal the bones from growing more. Sometimes estrogen is given to prepubertal girls by doctors who believe they are growing too tall too soon, which will likely go down as a

bad idea

in the annals of pediatric medicine.)

Having a long childhood, though, takes a toll on parents and society. Kids need resources, a whopping 13 million calories approximately, before reaching adulthood. For some populations of humans—those with fewer resources—that toll is harder than for others. This may partly explain the great natural variation in age of puberty from eleven or twelve to sixteen. Although girls tend to reach puberty about the same time their mothers did, there’s still a lot of wiggle room.

Here’s where we give another nod to the power of our environment. Breasts are like little antennae, processing information

out there in the neighborhood and bringing it home. Among other things, the environment tells breasts when to show up. Evolution designed our bodies to be responsive to all sorts of cues, including the nutritional status of our mothers and even, remarkably, our grandmothers.

Even though genes account for some of the timing of puberty, the environment determines when and how the genes get switched on. When a woman’s prenatal nutrition is good, her baby’s fetal cells program themselves for earlier puberty. When it’s lousy, the opposite occurs. And along the way, there’s still opportunity for course corrections. When poor, once-hungry immigrants move to industrial countries, suddenly encountering “nutritional excess,” the girls’ bodies recalibrate. Adopted Indian girls who move to Sweden as infants, for example, reach puberty uncommonly early. They also gain weight faster than their Scandinavian peers, having been programmed in the womb to store more calories as fat.