Breasts (17 page)

Authors: Florence Williams

Tags: #Life science, women's studies, health, women's health, environmental science

The other major event was the rise of germ theory. It changed modern medicine forever, and much along with it. In a nutshell, this was the recognition that microbes caused disease. Before that, people thought sickness was caused by swamp vapors or spontaneous eruptions or a combination of bad luck, bad behavior, and God. In 1876, the German physician Robert Koch proved the bacterium

Bacillus anthracis

caused anthrax in livestock, and he discovered the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. Over the next twenty years, microbiologists isolated the organisms that cause pneumonia, diphtheria, typhoid, cholera, strep and staph infections, tetanus, meningitis, and gonorrhea. In one sense, an environmental understanding of disease was being replaced by a germ-based one. It represented medical progress, but it would ultimately provide a false sense of separation from nature.

The new discoveries led to many vaccines and antibiotics, as well as to vastly improved sanitation measures, quarantines, and food safety practices, such as pasteurization. Many, many lives were saved. You might think an understanding of deadly bacteria would bolster the argument for breast-feeding and against commercially processed infant foods, but the opposite happened. Medicine and science enjoyed a new prestige, and mothers grew more willing to surrender traditional knowledge and personal control over infant care. The midwives and grandmothers didn’t stand a chance. In 1920, only 20 percent of American women gave birth in hospitals; by 1950, over 80 percent did. There, scientific motherhood flourished.

Such science did not look favorably upon breast-feeding. Mid-century mothers were often totally anesthetized for childbirth, necessitating the use of forceps to pull the baby out. After birth, babies were typically given formula to wait out the period of time before the mother’s milk came in (around three days, but before that she makes immune-boosting colostrum). Babies and mothers were separated at birth, only to be reunited for short, closely regulated, and highly sanitized feedings. Talk about some weird amendments to our eons-old mammalian patterns: mothers

wore masks, scrubbed their nipples with soap, nursed their babies, and then watched them get burped through Plexiglas windows. To allow the mothers to rest, nurses took over the night feeding with formula freely supplied by manufacturers. Only several other feeds were allowed during the day, usually with one breast at each feed. It’s no wonder the mothers didn’t produce enough milk. The babies became hungry, and the bottle was presented as a perfectly acceptable alternative. The doctors and nurses had little-to-no training in lactation but much expertise in formula measurements. After a week of the Nurse Ratched approach to baby care, mother was sent home with a pat on the back and a free sample of Nestlé’s finest.

In 1956, a small backlash ensued. It started in Illinois at a church picnic with a couple of Catholic matrons, not normally known for upholding mammalian urges. “It just didn’t seem fair that mothers who bottle feed … were given all sorts of help … but … when a mother was breastfeeding, the only advice she was given was to give the baby cow’s milk,” said Marian Thompson. She and Mary White formed a small group to support other breast-feeding mothers. They called themselves the La Leche League. As one of the founding members told the

New York Times,

“You didn’t mention ‘breast’ in print unless you were talking about Jean Harlow.”

You probably know the tale from here. The suburban La Leche ladies went on to align with the hippies and the back-to-landers, and together they reformed hospital practices and reversed the sorry downward spiral of breast-feeding rates. Then they took on Nestlé through an epic boycott over its capitalist hegemony in developing countries, where infants were dying from formula made with contaminated water. The league is alternately inspirational and infuriatingly

dogmatic. For a time, it advocated that mothers stay home and not work. This proscription did not sit well with the emerging feminist movement in the 1970s, and tensions over their take-noprisoners attitude remain to this day. Still, the organization has effectively hammered home its central message that breast-feeding makes babies smarter, healthier (those ear infections!), less obese, more loved, and pretty much superior in every way.

The lactivists, both nationally and globally, have made their milky mark: the World Health Organization now recommends breast-feeding for two years; the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends it for one. Many hospitals still distribute free formula (mine did), but they also allow “rooming in” so new mothers and babies can spend all their time together; often, baby is put to breast within moments of delivery.

Even so, American mothers learning to breast-feed are uniquely beset by problems. It normally takes about three days after childbirth for a mother’s milk to “come in.” Any longer than that, and the docs are going to whisk Junior away and start formula. So the early days are critical for the long-term success of nursing. In Ghana, only 4 percent of women experience delayed lactation; in Sacramento, site of a recent study, 44 percent do. No one knows why. It might be because we’re more obese or older, or we use spinal anesthesia, or we have more C-sections or more environmental exposures, or tight bras have flattened our nipples.

Stay tuned; it’s an active area of research.

Despite the lactivists’ best efforts and deepest intonations of “breast is best,” breast-feeding rates here and in much of the world remain middling. In the United States, about 70 percent of mothers initiate breast-feeding, but only 33 percent nurse longer than six months and only 13 percent fulfill the year-long recommendation.

Australia and Sweden, with their generous maternal leave policies, have gone lactomanic, with initiation rates of over 90 percent. Canada’s is about 87 percent. Brazil has been a great public health success story: The average duration of breast-feeding has increased from two and a half months in the 1970s to over eleven months today. Over 95 percent of Brazilian women try breast-feeding, and for those who can’t swing it, the country has two hundred human milk banks and over 100,000 donors. Their milk is collected and stored by firefighters.

Has all the ruckus—all the maternal guilt, the physical and mental introspection, the

madre-a-madre

name-calling, the battles with the medical establishment—been worth it? Is milk,

au naturel,

really so superior to formula that we must make each other feel bad about our failures and choices? The honest answer to this question is yes and no. I don’t mean to be feckless. Breast milk confers many known benefits to infants, but for healthy babies in the developed world, those benefits are relatively small. They might actually be bigger than we think, but the truth is, we don’t really know. To some extent, the activists asserting we’re in the midst of “a biocultural crisis” have perhaps overstated their case.

The journalist Hanna Rosin wrote a compelling essay challenging breast-feeding in a much talked-about

Atlantic

article in 2009: “And in any case, if a breast-feeding mother is miserable, or stressed out, or alienated by nursing, as many women are, if her marriage is under stress and breast-feeding is making things worse, surely that can have a greater effect on a kid’s future success than a few IQ points… So overall, yes, breast is probably best. But not so much better that formula deserves the label of ‘public health menace,’ alongside smoking.”

It was a strong argument delivered well for an

Altantic

readership.

Who needs a few extra IQ points or a few less visits to the doctor when our children will be high achieving and successful anyway? Given the context, it’s a reasonable stance. And refreshing, a welcome astringent to the sanctimony of the lechistas. I’m sure many mothers read it and gleefully ran out to the market—perhaps Whole Foods in their case—to buy Earth’s Best Soy Infant Formula. After all, most of us weren’t breast-fed and look at us: we’re healthy, long-lived, long limbed, and terribly clever with iPhone apps.

Then again, once you look outside Rosin’s reader demographic, a lot of us are rather obese. And diabetic. On the road to heart disease? Check. And because of all this, some of us will be facing shorter lifespans than our parents. Allergies and asthma? Common. (And a word about the IQ scores: formula confers the same average loss in points—four—as high childhood lead levels. That dip was enough to trigger a public health outcry in the 1970s, and resulted in federal laws banning lead in gasoline and paint. Now kids’ scores are back up.) But can we attribute any of our metabolic malaise and chronic ill health to formula? Some people are trying, and they’re trying hard. So far, the data are intriguing, but underwhelming.

Many studies, for example, have compared formula and breastfeeding for a risk of obesity in infants and children. The results of these studies, it must be said, are all over the map. Two major reviews of the literature found that in a majority of studies, children who were breast-fed faced a lower risk—ranging from about 10 to 25 percent—of obesity. Despite the fact that most of these studies rigorously controlled for factors such as the mother’s level of education, smoking, and so on, other confounding factors might exist, so it’s difficult to know for sure how much of the benefit to attribute to breast-feeding. It is known, however, that formula-fed babies consume

about 70 percent more protein than their peers, and this may trigger higher levels of growth factors and insulin secretion, which in turn lead to increased deposition of fat.

Since it’s hard to see big bangs from breast-feeding in countries where kids are generally healthy and well taken care of, I wanted to look elsewhere. The data start to get really electric when you peer farther over the fence into areas of poverty or the world of preemies and sick babies.

I owed it to breasts to check it out. So I headed for Peru.

HOLY CRAP:

HERMAN, HAMLET, AND THE

ALL-IMPORTANT HUMAN GUT

O, thou with the beautiful face, may the child Reared on your milk, attain a long life, like The gods made immortal with drinks of nectar.

—SUSRUTA SAMHITA,

fourth to second centuries BC

L

IMA HOSTED THE FIFTEENTH MEETING OF THE INTER

national Society for Research in Human Milk and Lactation during a cool austral spring week in October. The society’s cochair, Professor Peter Hartmann, welcomed me heartily. “We’ve never had a journalist before! Maybe you can tell people about our work!”

Hartmann, an Australian now in his seventies, is perhaps the world’s foremost expert in lactation. Even so, he bears the demeanor of someone whose work is largely unacknowledged outside this crowd. He’s a little bent over, and quiet, and a bit harried. He spent the week in Lima clutching his briefcase and scurrying from meals

to meetings wearing his beret and a leather jacket. His son, Ben, is also here, not quite as stooped or as sartorial. Ben, thirty-four, runs a milk bank, collecting and storing donated human milk for use in the preemie ward of King Edward Memorial Hospital on the edge of Perth. (What is it with fathers and sons dove-tailing careers around breasts? Ben’s infant, Arlo Peter, has actively benefited from the Hartmann male tradition. “As my poor wife has indeed been subjected to the full barrage of tests by the research group, we certainly had a lot more information at our fingertips than most,” said Ben.)

I sat down with the elder Hartmann during one of the numerous café breaks in a heavily tiled, open-air meeting room at our faux-Renaissance lodge. Originally, he told me, he intended to study dairy science. He got a Ph.D. in bovine lactation. But then Britain changed its export policy, and the Australian dairy market “disappeared overnight,” he said. He secured a lectureship in biochemistry at the University of Western Australia in Perth, and in 1971, his first child was born. That event piqued his interest in the human side of things. He started studying progesterone withdrawal in women after birth, and found a large pool of enthusiastic breast-feeding volunteers through the Australian version of La Leche League. Human lactation was a tough academic sell, though. “Nobody was really interested when I applied for grants. It wasn’t a good career choice.” He smiled impishly, then added, “I proved them wrong.”

Still, he said, “It’s amazing how few people are interested in this incredible organ. The breast is the only organ without a medical specialty. It represents 30 percent of a woman’s energy output, and it’s not represented by a specialty! It’s absolutely appalling!” What he meant by the energy bit is that while a woman is lactating, the metabolic energy required to feed her infant is 30 percent

of her total output—or the energy equivalent of walking seven miles—every day. Looked at another way, a male baby requires almost 1,000 megajoules of energy the first year of life. That is the equivalent of one thousand light trucks moving one hundred miles per hour. As the ecologist and writer Sandra Steingraber has put it, “Breastfeeding is a form of matrotropy: eating one’s mother.” No wonder so many women are ambivalent about doing it.

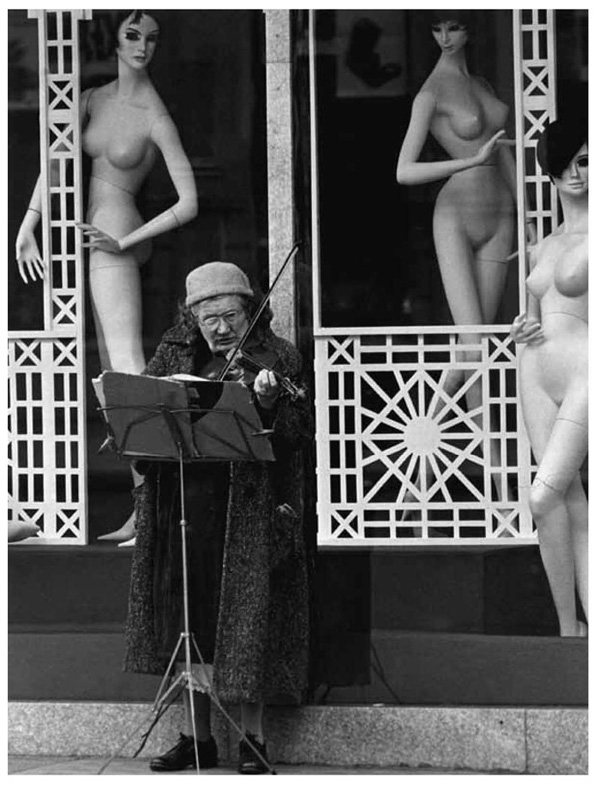

“It’s a magnificent organ to study from a molecular standpoint,” Hartmann continued, occasionally smoothing his trim white beard. “It’s easy to get access to it and harvest molecules. The problem lies with the view of it as an aesthetic breast. You only have to go to the local newspaper and see breasts hanging all over the place.” (Hartmann must be one of the few Western men on the planet who see this as unfortunate.) “The problem is the view of the aesthetic breast gets in the way of the view of the breast-feeding breast. The guys at the tennis club joke they wish they had my job, but no one is

doing

my job. At other [biological] meetings, you see thousands of scientists. We’ve got less than a hundred.”

He’s right that breasts are often overlooked, at least for noncancer scientific research. The Human Microbiome Project, for example, is decoding the microbial genes of every major human gland, liquid, and orifice, from the mouth to the skin to the ears to the genitals. It neglected to include breast milk, the life-giving, lifesaving, older-than-mammals-themselves elixir. Oops.

There is at least one entity very interested in Hartmann’s research, and that is Medela, the Swiss maker of breast pumps. The company sent a number of representatives to Lima, and they presented a poster explaining their latest product. It’s a new artificial “teat”—that’s Australian for

nipple

—based entirely on Hartmann’s lab studies regarding flow and suction. I know a thing or two about

suction. Just talking about it makes me wince. The new teat is meant to be used with Medela bottles filled with pumped human milk.

The Hartmann lab in Perth is well regarded for upending prior notions of how sucking—technically,

suckling

—works. Experts used to think the infant squeezed the nipple with her tongue, rhythmically releasing milk through this peristaltic action, a bit like wringing a washcloth. But Hartmann and his colleagues, using high-tech ultrasound videos, showed that the baby forms a strong suction with her lips, and it’s when she

releases

the nipple that milk flows down her throat (and moreover, this being a specialized human infant, she can suck and breathe at the same time, unlike adults).

One day some years ago, Hartmann was flying over Australia, and he found himself gazing out at giant ore piles near the mines. They were large mounds of salt and minerals, smooth and gently rounded. They looked like … his favorite organ. From high in the sky, a stockpile looked just like a breast from a few feet away. It occurred to him that it might be possible to apply giant-earth stereoscopic measuring techniques to the human breast. But he wasn’t merely interested in measuring the volume of a breast; he wanted to measure the synthesis of milk.

“Humans do not produce milk at full capacity, like a dairy cow,” he said. “They down-regulate to match the baby’s appetite. So we had to learn about those differences. How do you measure milk synthesis in a woman? I thought maybe if you could measure the volume of the breast, you could measure synthesis.” So he approached an expert in a mine-measuring technology called Moiré topography, and together they figured out how to calibrate units in something other than metric tons. They call it CBM, for computerized

b

reast

m

easurement, and it has to do with projecting light stripes at an angle onto the breast. “The distortion of the stripes

could let you work out the volume of breast!” said Hartmann. “We could do it before and after feeds over a twenty-four-hour period. The difference in volume is the short-term synthesis [of milk] from one breast-feed to another!”

In the old days, people used to measure milk output by simply weighing the baby before and after a feed, but that didn’t reveal information about the workings of each breast independently, or about how much milk a breast could make from hour to hour or day to day. These data could be useful to hospitals, doctors, and, of course, Medela, which funded the research. In a paper describing the work, Hartmann and colleagues found that each breast of the average new mother produces approximately 454 grams, or 16 ounces, every twenty-four hours. Each breast can store about half of that, and both actions are determined by the demand of the infant (one baby in the study ate twice the average). Check this out: even after fifteen months of lactation, each breast can still make 208 grams of milk, even though the breast has

returned to its pre-pregnancy size.

In other words, the breast becomes more efficient, possibly owing to a “redistribution of tissues within the breast,” according to the paper by Hartmann’s lab. Breasts should get an Energy Star rating.

In any case, thanks to Hartmann, no longer is the dairy machinery such a mystery.

But the dairy

product

still is. I wanted to find out more. What makes milk so special, if it really is? A lot of Hartmann’s work is in the liquid physics arena, but many of the Peru attendees were molecular biologists, biochemists, or geneticists who are deconstructing the components of milk bit by bit. They’ve been doing this for well over thirty years, and you’d think they’d have figured it out by now. Until very recently, it was thought that breast milk had around two hundred components in it. These could be divided into

the major ingredients of fats, sugars, proteins, and enzymes. But new technologies have allowed researchers to look deeper into each of these categories and discover new ones altogether.

Scientists also used to think breast milk was sterile, like urine. But it turns out it’s more like cultured yogurt, with lots of live bacteria doing who knows what. These organisms evolved to be there for a reason, and somehow they’re helping us out. One leading theory is they act as a sort of vaccine, inoculating the infant gut so it can recognize bad actors and fight them when the need arises. At the conference, Mark McGuire, another former dairy scientist recruited to the human lactation field, described how he took forty-seven samples of milk, extracted DNA, and identified eight hundred (yes, eight hundred) species of bacteria living there, including small amounts of staph, strep, and pneumonia, all of which normally live in our bodies. An individual milk sample has anywhere from one hundred to six hundred species of bacteria. Most are new to science.

Then take the sugars. There’s a class of them called oligosaccharides, which are long chains of complex sugars. Scientists have identified 140 of them so far, and estimate there are about 200 of these alone. The human body is full of oligosaccharides, which ride on our cells attached to proteins and lipids. But the mother’s mammary gland cooks up a unique batch of “free,” or unattached ones and deposits them in milk. These are found nowhere else in nature, and not every mother produces the same ones, since they vary by blood type. Even though they’re sugars, the oligosaccharides are, weirdly, not digestible by infants. Yet they are a main ingredient, present in milk in the same percentage as the proteins and in higher amounts than the fats. So what are they doing there?

They don’t feed us, but they do feed many different types of beneficial bacteria that make a home in our guts and help us fight

infections. In addition to recruiting the good bugs, these sugars prevent the bad bugs from hanging around. They act as “anti-adhesives,” kicking the bad guys off the gut surface. Some also seem to handcuff themselves to the criminals and escort them off the premises like a micro paddy wagon. “I think the benefits of human milk are still underestimated,” said Lars Bode, an immunobiologist at the University of California, San Diego. “We’re

still

discovering functional components of breast milk using new technologies and using smaller amounts of milk.”

Bode told me it’s well established that premature infants do remarkably better—as in, an order of magnitude better—on breast milk than on formula. As we’ve been able to keep younger and younger preemies alive, they’re more likely to be very sick. About 10 percent of preemies will suffer from a dreadful disease called NEC, or necrotizing enterocolitis, and about a fourth of those will die from it. NEC is a gut infection that causes the lower intestine to shrivel up and die. Babies who survive this often must have the necrotic portion surgically removed, leaving them with a condition called shortgut syndrome. Because they can no longer adequately digest food, they spend the rest of their lives attached to an IV.

But the incidence of NEC is 77 percent lower in breast-fed babies than in formula-fed babies.

This is why neonatal units work so hard to get mothers to pump breast milk for their preemies’ feeding tubes. In lieu of that, they use donated milk from milk banks, and in lieu of that, they can buy a newfangled “fortifier” made from concentrated

human milk

by a company called Prolacta Bioscience. It costs $12,000 per baby.

Naturally, conventional formula companies are falling all over themselves to synthesize these unique human sugars and add them to their cow-milk products. So far, they’ve been able to re-create only a few of the simpler ones, and to not much effect. These newly

enriched formulas, for example, do not alter preemie NEC rates, according to Bode. This is because the most “bioactive” molecules are the bigger, more complex oligosaccharides, which are incredibly difficult to make in a lab. “Take one of these special monosaccharides? If you wanted to supplement human milk with it, the package would cost half a million dollars,” he said.

Bode said his lab has also shown that a simpler chain, called GOS, is effective at fighting amoebiasis, a parasite that kills 100,000 people a year. It’s likely GOS could help adults as well as babies.

THE GUT, IT TURNS OUT, IS INCREDIBLY IMPORTANT NOT JUST TO

infant health but to adult health as well. Bruce German, a food chemist from the University of California, Davis, drove this point home for me. Picking up the breast ball where the Human Microbiome Project dropped it, German is spearheading the Infant Microbiome Project at the university’s Foods For Health Institute. The idea is to map and characterize oligosaccharides, as well as other human milk components, for eventual infant and adult medical applications. As German put it in a recent video, “We’ll take little tiny droplets of milk and disassemble them completely, understand every single molecule in it … and how they function when ingested by infants… We’re confident it will teach us how to prevent diseases like diabetes and heart disease and ultimately even cure diseases like cancer.”

German speaks in superlatives and alluring metaphors even when he’s not being filmed. “The genomic tree of life is a compelling one,” he told me in a private mini-lecture on microflora over breakfast one morning. A wiry, almost hyper speaker, he began to turn red. “We’re just a tiny branch! The rest of it is all microbial! We’re

just a small part of the mass of microbial life. To a large extent, we live our life at their say-so. We have to form a pact with the world around us. Recruiting protective microflora is the very first thing we do in life.” He wasn’t eating, but now he sipped his coffee. “Put yourself in the mindset of an infant. You’re born, you are dropped in the mud, literally, where the microbial community thinks of us as lunch. So you must develop a community that protects you for life.”