Bronson (27 page)

Authors: Charles Bronson

So here I am, heaping on the praise. But then what happens? A man causes me to flip. All this good work was going on, and – for me – it turned to dust in seconds.

It was Easter Monday and the last three days had been magic. ‘O Come All Ye Faithful’ was still a big joke to us all. The unit was buzzing, alive.

It was about 9.00am, and the boys and myself were in the kitchen preparing breakfast. I was the porridge man; I used to make the porridge every day. Paul was sorting the eggs out; Eddie was making the tea, and Tony was having a fag. This was like any other, normal day. There were no upsets and we were all OK … until a governor appeared. Adrian Wallace was the Deputy Governor of Hull and also the unit governor. When I saw him that morning in his blue, pin-striped suit, I felt the sweat running down my neck – and then I lost control of my senses.

I ran at him … and in seconds he was my hostage. My insanity had broken free once more. Months of pent-up madness were pouring out of me. My eyes were bulging and my whole body ached for excitement.

I had Wallace in a Japanese strangle-hold. I screamed at everyone, ‘Come near me and I’ll snap his neck!’

Easter Monday was mine and this unit was mine. I was the Governor today!

I shouted to the lads not to get involved. Tony, Paul and Eddie all looked stunned. I shouted out to them, ‘Cheer up, lads, Happy Easter!’

The screws started to crowd around. I told them to stay back. I could feel Wallace trembling. I dragged

him into one of the TV rooms and barricaded it up with tables and chairs. I then took his tie off and tied his hands up behind his back. The Hull siege (well, my first Hull siege!) had begun.

I sat Wallace down on a chair in the middle of the room and then grabbed his keys and went through his pockets. His credit cards went flying; I ripped up the bank notes. I went wild, kicking over furniture. It was a crazy scene. Rock music was blaring out from a telly I’d turned up.

‘You’re a bastard, a bag of shit!’ I grabbed an iron that was in the room. ‘Don’t move or I’ll kill you. I’ll batter you with this, c--t!’

I demanded a couple of cups of tea for me and for Wallace, and after a few minutes two steaming mugs of cha were pushed through the barricades. I love a cup of tea! Helps calm me down. I undid Wallace’s hands so he could drink his tea.

Then I used the man’s radio to order them to shut the whole fucking prison down. Soon it was Wallace’s turn to relay a message. I wanted the blow-up doll I’d been denied at Woodhill – plus steak and chips twice!

I grabbed Wallace around the neck and walked him along the corridor to the next TV room. I barricaded the place up and told him I was going to sing ‘I Believe’, the song I wanted playing at my funeral. (I was sure police marksmen would soon surround the place, and I have to say that, at that moment, I was prepared to go out fighting.)

Sing it I did, at the top of my voice! Then I made a mistake. I tried to get back to the other TV room with my hostage. I loosened my grip on his neck as I went for the door handle and I lost my balance and was rushed by screws. Wallace started kicking me in the face and body. I was overpowered.

I left Hull the same day … stripped naked and put in the body-belt. Once in the van, I felt

numbness to the right side of my face. I had a terrible headache that caused me to feel sick and dizzy. It was a good two-hour journey before the van drove into Leicester Prison.

The door opened and the seven screws and I jumped out. There were governors, screws, members of the Board of Visitors. And all saw my nakedness. They led the way to the steps that would take me to the punishment block. It was like some crazy dream. As I walked barefoot through the puddles outside, I thought about the past, the good times, the moments of joy. I just didn’t want to face up to reality. But the screws’ faces said it all. They believed I was a madman.

They took me to a cell where they took off the

body-belt

and gave me some food and a mug of hot tea. I can remember little else about that day. I drifted into a big, black cloud. All I could feel was the pain in my head. I couldn’t eat the food they had given me – I couldn’t even move my jaw up and down.

The next morning I awoke to the sound of the night screw getting ready to welcome the day screws. My jaw was hurting like hell. I had cuts and lumps all over my head and I think that the muscle in my right shoulder had been torn. I felt terrible.

As my door unlocked, I rolled out of bed to see the familiar face of a screw who I knew. He was a decent old boy and had always treated me OK, so I gave him respect. I told him about the pain I was getting with my jaw. He soon got a doctor over to see me. As you know, I despise prison doctors. But at times you have to give in. This was one of those times. He examined me and told me that I would have to have an X-ray. He also noted in writing the injuries to my head.

The screws in Leicester were no trouble to me. They gave me no shit and there was an element of trust between us. They allowed me to make a call to

Loraine. She was gutted when I told her what had happened. She always cheers me up does my Loraine. She made me promise to her that I would stay cool. She’s the governor in my eyes, so I made the promise, gave my respects to her husband Andy, and hung up. As soon as I went back to my cell, I went to sleep. It was obvious that I was suffering from concussion. I remember very little of the rest of that day.

On 6 April, I heard my door unlock at 8.00am – I presumed for breakfast. But there were a dozen screws and a governor standing there. Before they said anything, I knew that it was time for me to move on again.

‘What about my fucking X-ray?’ I asked. The Governor assured me that I would have it done where I was going next.

‘Where’s that?’ I asked.

‘Wakefield,’ he replied. ‘But it will only be temporary.’

I knew that the Home Office didn’t have a fucking clue what to do with me. They had helped to create me, and now they couldn’t control me. They are such short-sighted, petty-minded, vindictive bastards.

The belt went on once again and off we went – back up north. I wasn’t happy. My head was throbbing, my jaw ached and I was thoroughly pissed off. I stayed silent throughout the journey. I had no reason to slag off the Leicester screws in the van. They were only doing their job and they had done me no wrong. I did a lot of thinking during that journey. I wondered if I would ever be free again. I thought that if I didn’t get a life sentence over the Woodhill siege, then I was bound to get one over the Hull one.

I’d been digging myself into a fucking big hole, and holes couldn’t come bigger than this.

* * *

Wakefield Prison. The Hannibal Cage.

The whole of Britain must know by now about the ‘Hannibal Cage’. It was plastered all over the newspapers. This cage was ten times worse than the last cage I was in, here in Wakefield.

It was total isolation.

Being locked in there could quite easily destroy a man. It is potentially the last bus-stop before total insanity – or death.

It was the only cage of its kind in the whole British prison system. The last convict to be held there was Bob Maudsley. Bob was jailed for life in 1974 for stabbing and garrotting his uncle. He later killed three cons. One was a hostage in Broadmoor, who he tortured and, when he was finally dead, held aloft to show the screws who had been negotiating for his release. Then there were two cons he killed in Wakefield. He reputedly cut open the head of one of his victims and ate his brains with a spoon.

For the three-and-a-half years since Bob had left, the cage had remained closed.

Now they had opened it up again – just for me. The cage was a living death, a total void. It has its own toilet and shower, so there is no human contact at all. All meals are put on a table ten feet away from the cage doors. When I was unlocked to collect my meals, there were never fewer than a dozen screws standing by. Once I counted 15. Thirty eyes watching my every move.

This procedure happened three times a day. It was the only time that I actually left my cell. I was not allowed any exercise, neither was I allowed any visits apart from legal ones. When my solicitor or probation officer visited me, they had to sit outside the cage door. We could not even shake hands. We had to talk through the steel net in the cage door. There are two

doors to this cage. The outer one is solid steel and has an observation slit in it. The inner door is also steel, with the steel net across it.

The inner door has a 1ft-wide gap in the bottom, through which I was passed a cup of tea at supper time.

Sheets of bullet-proof glass form one section of the cell wall. Through these I could be observed 24 hours a day. My table and chair were made of compressed cardboard and my cutlery and plates were plastic. My bed was bolted to the concrete floor.

The walls are reinforced steel and concrete. The bars on the windows are solid steel. A steel cage is attached to the outside of the window.

I was forever pacing up and down, naked except for a blanket. I had a lot of time to think. The Cage is the end of the line. The silence is the madness. Fantasy becomes reality. There is nothing to look at, no one to talk to and no one to listen. You are the living dead. Dreams and nightmares, day and night, merge seamlessly.

You are empty, utterly empty. You are as lost as the coma victim who can hear what goes on around him but can only blink helplessly to an unknowing world.

To be stranded in a desert with no water, weak limbs and merely the faintest hope of survival is one thing. To be stranded without hope, yet surrounded by people who could really help, is another.

But I still had my dreams, however fragile they might be. To stop dreaming is to stop breathing.

On Thursday, 28 April 1994, the cops came to my cage door.

I was charged, through the bars, by Humberside Constabulary, with: (1) False Imprisonment; (2) Threats to Kill; (3) Actual Bodily Harm; (4) Criminal Damage; (5) Criminal Damage.

These five charges were the result of the Hull siege. At 15.35 hours the police walked away from my cage.

I’d made no comment, merely nodded and grunted. The cops had looked shocked to see me in such a medieval cage. As they left, I shouted out, ‘Next time, bring me some pies.’

The outer door slammed shut and I was alone.

So here I was, again awaiting another trial, another load of mental pain. There seemed to be no end. And maybe there isn’t.

I realised that I had been waging a war, a war that had gone on now for 20 years.

During this war I had gained a reputation, but nothing more. In fact I had lost almost everything – not just my wife and son, my home and my liberty. I was now not just a Category A convict. And I was not just Category A and in solitary confinement. I had now been branded the worst of the worst. A man held in a Hannibal Cage.

Prison and the asylums had made me worse, not better. I had truly become a hostage of my past,

condemned by my reputation and my fucked-up mind.

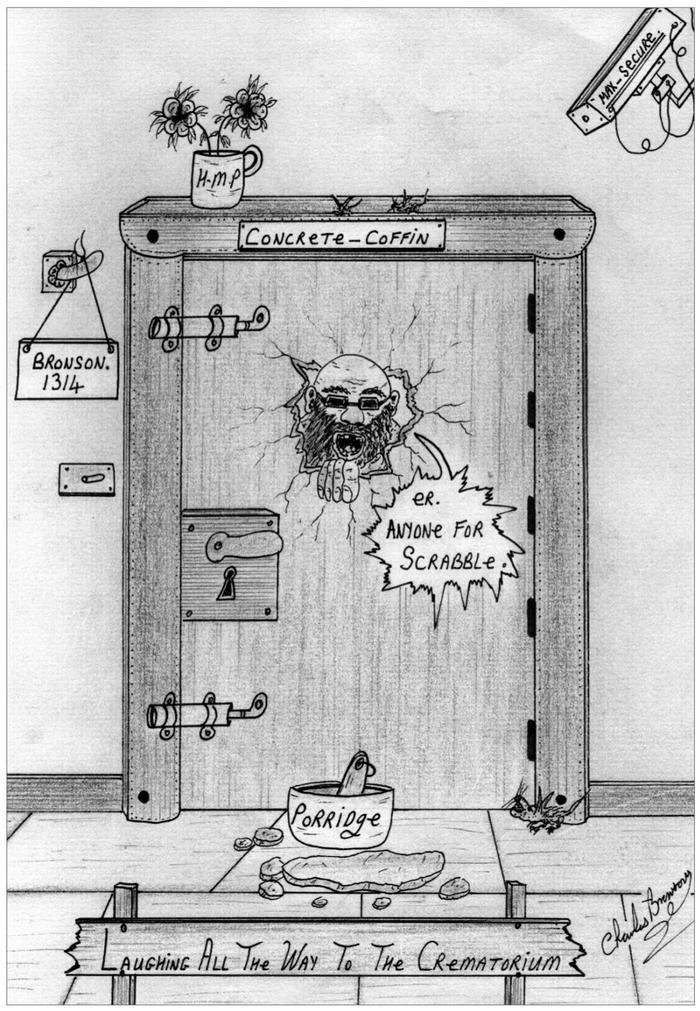

But one day in that cage at Wakefield there was a glimmer of hope. Apart from trying to build the pond at Parkhurst, when I’d been stabbed, I’d never tried to do anything positive or creative with my life. Some cons become born-again Christians. I became a

born-again

cartoonist!

I’ve actually met some good screws on my journey, and if more were like Prison Officer Mick O’Hagan I might have had a fighting chance of a relatively normal life. PO O’Hagan ran the seg unit in Wakefield. He’s in his late 50s, 6ft tall and 200lb – a man’s man. He’s no soft touch. But he’s the fairest screw you could ever meet. If you’re OK, he’s OK, and you will get what you’re entitled to. No more, no less. He was a good boxer in his day, but I like him because he doesn’t take life too seriously. He has time to laugh and sees the funny side of it all. He doesn’t look down on us cons. PO O’Hagan has always taken the time to come to my cage door and ask how I am. He’s shown me humanity.

One day, Mr O’Hagan came to my cage door and told me his true opinion. He told me I wasn’t stupid; I should start boxing it clever. Why didn’t I start studying, learning about art, poetry and writing?

Why not?

I had nothing to lose, and potentially a lot to gain. Not freedom, not parole even, but a feeling of

self-worth

for the first time in many years. Sure, I was hard, I was strong – but where was my life going?

He got me pens, pencils, rubbers, rulers and loads of paper. It was the best thing that ever happened to me. I sat alone at my cardboard table, went inside myself, and created. I taught myself how to draw, and I got better and better. Mr O’Hagan always encouraged me.

I’ve since won seven major prison prizes – in the

Koestler Awards – for my writing, art and poetry. Seven in eight years, and one year I didn’t even enter (I got two awards the next year). The Koestler scheme was the brainchild of the famous author Arthur Koestler. He believed passionately in social reform, and in 1961 he agreed the details of the scheme with the then Home Secretary, Rab Butler. One art critic described my paintings and drawings as the ‘work of a madman’. But how closely linked are insanity and genius? Van Gogh cut his ear off, after all!

So I take my hat off to Mr O’Hagan, and to another decent screw in Wakefield, Mr Maguire. He’s also a man I’ve got nothing but respect for. I’d buy him a pint any time. They couldn’t do a lot to make my time in the cage better, but what they did do was show me some respect and humanity. They’d come to my door to chat about boxing, soccer, what was going on in the world. Even if it was only ten minutes a day, they made the effort. There are other screws – and they know it – who I’d lay out given half the chance. They are nothing but bully boys with peanut brains. They are just power-crazed, faceless hobbits. They know to steer clear of me, and I don’t talk to them.

A nun called Sister Carmel used to see me most days. She’d sit outside my door and talk. Now let’s get this straight; I’ve normally got no time for sky-pilots in jail. Most strike me as hypocrites. I remember one in another seg unit years earlier. He saw the screws kicking nine bells out of me. He actually turned around and walked away. A few days later when he was doing his rounds, I put it on him. ‘Oi!’ I said. ‘I saw you. You’re a fucking disgrace, a coward. Jesus would have seen you walk away, too, so he knows the strength of you! Now fuck off before I chin you.’

But Sister Carmel was a gentle soul, a wonderful lady with an angelic smile. I’d sit on my cardboard chair and talk to her through the steel gate. It’s not

easy to see out, because of the cage welded to it. Lord Longford also came to see me. His eyes filled up; he said in 50 years of visiting prisons he had never seen anything like it.

I trained alone in that cage. I would pace up and down, stop, and do 50 press-ups. Some days I’d get through 3,000. I had to have a routine. It’s the only way of dealing with solitary. There are some days when you can’t motivate yourself, just like in normal life. Depression sets in. That’s when I know I am lucky to be caged … when I know I can get dangerous.

It was a little over a month after I landed in Wakefield when they came mob-handed for me. The body-belt went on and I was taken to Bullingdon in Oxfordshire where I was held for a little over a week so I could appear at Luton magistrates over the Hull siege. On the way back to Wakefield, all hell broke loose. The van got a puncture and ended up on the motorway hard shoulder. There were cop cars, sirens, the lot. I was whizzed off in a police van to Leicester, where I spent the night in the seg unit. Then, on 18 May 1994, I was back home in my cage at Wakefield.

It wasn’t to last. Governor Parry came up to me. He explained there was going to be a lot of noise over the next few months with workmen in the seg unit. After years in isolation, noise and sudden movements affect me badly. I had a choice. I could stay and they would give me ear-plugs, or I could go back on the circuit, the rounds of Cat A blocks. I thought it over. I knew I would get headaches and possibly snap with all the noise. I said simply, ‘Move me.’

Strangeways seg had changed since the massive riot there. It was June 1994 and there were new rules and new ideas. I had a big reception committee waiting, but the seg screws were decent to me. They got me a running machine and locked me in an empty cell to exercise. The food was great and my cell was

clean. But I knew I would never get on with Governor Munn. I told him straight; if I had an axe, I’d hit him with it. At least he knew where he stood.

After a week, some silly fucker moved next door. He kept knocking on my wall.

‘Oi, mate. Got any burn?’

No, I don’t smoke pal. Sorry.

‘Got any drugs?’

‘Nope, I don’t touch them.’ This guy was bugging me.

‘You fucking southerners are all the same!’ he shouted. ‘Tight c--ts!’

The next day I took a quick look through his

spy-hole

before I went out on exercise. I memorised his face. You never know … one day.

Later, I wrapped up some of my shit in a little piece of cellophane and stuck it in a matchbox I’d found. I hid it in the shower room, and that night I banged on his wall. I told him where to find his ‘drugs’. The next day he picked up the parcel. Try and smoke that, sonny! I often play tricks like that on rats. I like to hear them shout out ‘I’ll fucking kill you!’ People like that make me feel unwell. They’re a waste to humanity.

A few weeks later, the van pulled up and I was off to my old hunting ground, Walton Jail and the seg unit. I know Walton’s dirty and tough, but it’s a man’s jail. You know where you are. The sad thing is there is always a mob of screws waiting for me, lined up with their sticks. Walton seg block can be the cruellest place on earth. But there are some older screws who treat me well and don’t harbour a grudge about me ripping the roof off in ’85.

Exactly a month later, I was in High Down, Surrey, a strange seg to me, with a load of muggy,

loud-mouthed

cons. I was edgy and getting violent again. I could feel myself going and I had to do thousands of

press-ups to release the tension. I knew I was like a walking bomb, and it seems they did, too. I lasted 11 days before, on 15 August, I was transported to Belmarsh Special Secure Unit on the outskirts of London. That was where I would see my dear old dad for the last time.

I knew that bunch of screws well, and they set up the visit with my dad like no other jail could. Even the governors helped to make it special. I was judged too dangerous to mix with other cons, but the screws knew my old man was dying of cancer. They let me, my dad and my brother Mark out on to the seg where they’d set up a table. There was a carton of orange juice and some cups for us. I helped them make it look nice for Dad.

When Dad came in with Mark, he looked weak and very tired. But he still had that spark, the fire in his eyes. He was a fighter until the end. I took him into my cell and Mark stayed outside. It was only a seg cell, but it was clean and I had a toilet and a sink as well as a window and a few bits and bobs lying around.

‘Bloody hell, son! It looks more like a flat!’

‘Yeah, Dad. I’m doing well now!’

We hugged and both started to fill up with tears. I told him how sorry I was that I was not out there to be with him. I told him I loved him. We went back out on to the landing and sat with Mark. Fuck me. It broke my heart to see my dad this way. But he was a brave man.

We both knew we would never see one another again.

When it was time for him to go, I felt myself getting a bit dangerous. I was upset, wound up. But I fought my urges – not for me, but for the sake of my dear old dad. Mick Reagan helped me a lot, although he may not know how much. He was on duty that day, and

whenever he was on duty, he made me feel calmer. He’s a good man who cares about good people.

As Dad walked out, I watched every single step he made. I knew that would be the last I would ever see of my father.

They went through the bullet-proof, electronic door. And then Dad turned, winked at me, and put his fists up in a fighting pose. That’s the last memory I have of the greatest man I’ve ever known. Mick Reagan put his hand on my shoulder and asked, ‘You OK, Chaz?’ I could only nod. I was too fucking cut up to speak. I managed to say thanks to all the screws – they’d been such a wonderful bunch that day. Then I banged up and cried my fucking heart out. Yeah, big men do cry.

The next day it was back to the old routine. It had to be to survive. I worked out. Press-ups, sit-ups, and I used my medicine ball. I call her ‘Bertha’. She’s seen me through a good few hours, has Bertha. I could never forget those last few moments with my dad. But for the moment I had to concentrate on my routine, otherwise I would have been completely destroyed. Within four weeks that routine was ruined. Someone in headquarters was having a laugh. I was off to Lincoln, a shit move that made no sense. I was being fucked around once more. I was there only three days. Then it was back in the van and off to the Scrubs.

I will never, ever, forget those maggots. By now you will most likely have heard or read a lot about brutality at Wormwood Scrubs. It’s a London jail with a bad reputation. Screws have now been suspended for beating cons. Whether they’re the guilty ones is anyone’s guess, but I can well remember the bastards who beat me within an inch of my life. The other allegations came years after I made my statement – against my nature, I have to say – to the cops in October 1994. Fuck-all happened as a result.

For me, it happened the week of my dear old dad’s

funeral. I arrived at the Scrubs on 16 September 1994. It was a tense start, so many eyes staring as I came in. Those faceless idiots took me out of my body-belt and led me to a cell to strip-search me. But there was one decent screw I remember from some time back. He winked at me as if to say, ‘Get your head down, Charlie!’ I said to him, ‘You still here, gaffer? Working in this piss-hole?’ He laughed and said, ‘It’s a job!’

‘Some fucking job,’ I said. ‘Why not work in an abattoir?’

The door slammed shut on my cell and I was alone once more. I searched it as I always do. You never know what you might find. Tools may come in handy later; drugs always get slung down the toilet. I remember once finding a £50 note in the hollow of the bed in a new cell.

Frank Fraser had sent me his book

Mad Frank

, so I settled down to read it. Then I tried to get into a routine with my press-ups. But every time the door opened I got the eye-ball treatment. It simply doesn’t work with me. I’ve seen it all before.

Then one cold September morning the call came that I had been fearing. They led me to the office and handed me the phone. It was Loraine. Dad was dead. He was only 70.

‘Charlie … you OK? Speak to me.’

‘Yeah, Loraine. Thanks for telling me. Keep an eye on Mum. Pull together, eh. And stay strong.’ Click.

A week later it was my father’s funeral. I desperately wanted to go, of course, but my request was blocked. I visited the prison church and sat there thinking about my dad, my family and about my treatment in prison. I wrote a message for the screws on a piece of paper:

I’ve had enough. I’m not playing games any

more. I’m going in the box. I want to be in silence – I don’t want to talk to anybody. I want no legal or social visits, no newspapers, no letters, no canteen, no clothes, no exercise.

I wanted to go in the strong box the next day, a Thursday morning.

I woke early and the door opened for slop out at about 7.30am. I walked out naked with my bucket and, as I was walking back to my cell, I saw there were about ten screws by my door. I went inside and picked up a jug of water and a toilet roll and said, ‘I’m off to the box.’