Bronson (31 page)

Authors: Charles Bronson

‘If you don’t keep quiet, I’m going to let Fred out.’

Fred had banged up. Fred liked Phil Danielson. He

also wouldn’t bat an eyelid about plunging him with a blade.

Danielson did as he was told.

I trashed the unit. The noise reverberated as I picked up the deep freezer, held it above my head, and slung it down the staircase. The cooker and other bits of furniture went the same way. The barricade was built. I doused it with cooking oil and soap in case I needed to fire it.

Dumb-bells from the gym went flying. I slapped a blob of butter over the lens of one of the security cameras to stop the screws prying. This was my unit now.

Danielson was squirming. He said it wasn’t him who’d slagged off my cartoon.

‘Charlie, it’s fine. We are waiting to get it framed up. The only thing I privately did wonder about … I just wonder if it smacked of all gay people spreading AIDS.’

I tied him to a chair.

Then I made a big mistake, one that almost killed me. I wrenched the washing machine off the wall in the utility room. Water spewed all over. The wires tore off. There was a bang and an almighty blue flash. I was thrown across the room as electricity surged through me.

I screamed and groaned. I thought I’d had a

heart-attack

. I was knocked out for several minutes. When I came to my face was as white as the driven snow. My hands were trembling.

I allowed Danielson to put his feet up on another chair. They were still tied. Then he said he was desperate for a cigarette.

‘I hate fucking smokers.’

‘All right, Charlie. I take it back. I’ll manage.’

‘OK. We’ll get you some. But I’m not talking to the fuckers.’

Later he got his wish. A cigarette was thrown down from the landing. And I threw something up, too. A note in a boxing glove to my girl Joyce Conner. She’s a Canadian serving a sentence at a women’s jail in Derbyshire. Joyce and I have never met, but she stands by me and writes me lovely letters. She’s a great artist, too. It’s obviously more platonic than anything, but she’s my princess.

I told Danielson to write a letter to his partner.

Then I told him to cut my ear off.

‘I can’t go to my grandma’s funeral, so cut the fucking thing off and bury it with her when you get out of here. I want a part of me alongside my granny in her grave.’

I still had my knife. I wanted the teacher to cut me with it. But then I got a blinding headache. The fucking fluorescent lights were doing my head in. I smashed them all with the point of a snooker cue. I calmed down a bit.

‘Phil, I believe you about the cartoon. I’ll make you a cup of tea soon. I know you’re cold. Don’t worry. You’re in shock – it will pass.’

I made my spear out of the knife and the snooker cue, and made Phil a cup of tea. Well, it was a plastic jug of tea and I had mine out of a coke bottle; I’d smashed all the cups earlier.

I was getting more anxious, more upset. I found an empty Newcastle Brown Ale bottle, held the neck and smashed the base off. I ripped open Danielson’s shirt and stood over him. I was in control – barely.

Charlie made no sound. He was just staring. I was absolutely petrified. I was as scared then as I had been at the beginning when I had the knife held at my ribs. The bottle was held at me for a few seconds and then Charlie stepped back. My hands were shaking. Charlie was still holding the bottle. He then, without making any sound, put the bottle to his head and scraped the

jagged edge down his bald head. Blood gushed from the cut down his face and on to his shoulders, chest and then the floor. I sat there, too terrified and too shocked to say or do anything.

‘I’m going to untie you now and we are going for a little walk.’

He tied one end of the skipping rope around my neck and held on to the other end. I felt very much Charlie’s slave – his puppet – and that he had full control over me. I felt total humiliation. This went on for about an hour. Then Charlie re-tied me.

This was a fucking long siege. I talked to the negotiators through the bars of the gate at the end of the unit and I let Phil chat to them. I tried to show him some compassion. I gave him blankets and made him cups of tea. But this was a siege that was to last 44 hours and we had to sleep at some point. I threw a mattress down on to a steel suicide net between the walkways of the landing and told Phil to jump on to it. The rope around his neck was tied to the netting. Awake or asleep, he was still my hostage.

The negotiators stood at the gate while we supped our tea. I could hardly keep my eyes open. They promised I could see my solicitor if I gave up peacefully. I decided to make a deal. Phil Danielson would stay another night, then we would walk out. My word was my bond.

I had a shower. I knew it would be my only chance for weeks. I opened a window. The YPs – the under-21 inmates – were shouting, ‘Charlie, Charlie! Have you done him? Is he dead?’

Charlie then shouted back a most unusual reply. ‘Look, you lot, do you realise what a good man this is, because I’ve just had a heart-attack and Phil has brought me around and given me the kiss of life?’

Some shouted back, ‘Ooooh!’

Charlie collapsed on the floor in fits of laughter. I

stuck my head out of the window. I heard shouts of, ‘Are you all right, Phil?’ and ‘Phil, you’re gonna get it. You’ll get your throat slit.’

I released Phil Danielson at 10.00am precisely. I walked out myself at just before 10.30am.

The van must have been using rocket fuel! They whisked me away and caged me up in record time. There were so many screws in the van with me that some were sitting on the floor on pillows. I was in the locked-up steel box in the back of the van, cuffed-up and in my monkey suit. I didn’t have a clue where I was going, but I sensed trouble. One of the screws was reading the Hull paper. I could see him through the box window. I was on the front page, and there were two more pages on the siege inside. I was shagged out, tired and fed up, so I closed my eyes and nodded off. I awoke when my head smashed against the inside of the steel box – there are no seat belts in those things. We were rolling through the gates of Whitemoor Prison in Cambridgeshire. We drove up to the back of the seg unit. Boy, were they in for a shock!

There were a good 20 of them waiting for me, most in riot gear. Hey! Tough guys! But I tell you what, they couldn’t even manage to open the lock on the box I was in! The lock was stuck. They brought in workmen with a grinder.

The noise, the sparks and the smoke were giving me a headache. I hate smoke. They still couldn’t get in. They were pissing me off.

‘Oi,’ I shouted. ‘Stand back!’

I gave the door a dozen good kicks, putting all my weight behind them. The door flew off!

They grabbed my arms and led me into the block where a cell was ready. Then all the shit started. I wasn’t allowed a toothbrush, it had to be kept outside my door. I had to stand up when the door unlocked. I couldn’t have my property. I said, ‘Hold up! Are you

saying I can’t do my cartoons?’ They said I could have one pen … no pencils, no rubber, no ruler.

Bollocks.

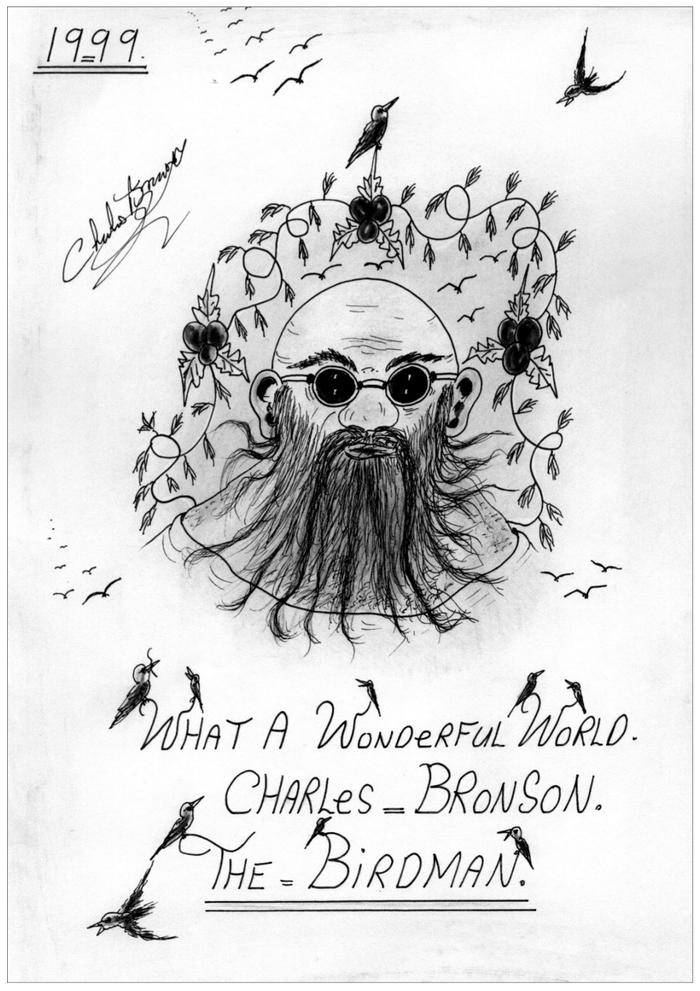

I made an official complaint but they overruled me. What was I to do? Sit and look at four tiny walls all day and every day. My art is my life. My one enjoyment. Why couldn’t I do it? What harm was there? Was it not bad enough being caged up?

Fuck it! I decided – no art, no life. I went on hunger-strike. For 30 days I took only water and tea, and throughout it all I was on a riot unlock. I was seriously weakening, but they would come in with helmets and shields and search me and my cell. They put food in, and then came to take it away again.

I was dying, slowly. This was not my way. My body is my temple; I’ve worked on it all my life, built it strong. Forget booze, fags, drugs.

I felt like I was blowing myself away.

My hunger-strike carried on another ten days.

I went 40 days, the same as Jesus had done. But he did it in the wilderness, not inside a concrete tomb. (Also, I reckon he ate shrubs, berries, plants, even the odd rabbit!) Me? I lost three-and-a-half stone. My muscles were wasting away.

But I survived and I’ve got to thank all the cons who gave me support – Tony Crabb, Richie Halliday, Barry Cheetham, Little Ali, Yellow and Fergie.

On April 23 1999, I was transferred back to Woodhill’s special secure unit – and that’s from where I’m telling you this story, the story of my life. I was a success here before, but they have put me on A wing. No privileges – nothing but the warehousing of a human being. They will not let me progress through the system, however well I behave. There are disturbed killers on better wings in the unit, yet I’m in a cell with no fresh air, no window to open. My bed is a concrete plinth six inches off the floor and I have

only two half-hour visits a month. Why should my old mum travel 250 miles for half-an-hour with me?

If I were Irish or black I could complain of racial prejudice. But I’m not. I’m Charles Bronson. I’m a dead man in a concrete coffin, caged up 23 hours a day. I’ve dug my own hole and they now seem determined to bury me in it.

I am like a fly in a spider’s web. I’m trapped. I can’t get out.

Will I have the life sucked from me? Will I be left as just an empty shell? Will I ever be trusted again? Would you trust a man who has spent almost all his adult life in cages and dungeons?

I doubt it.

I’ve lost almost everything, even the right to breathe fresh air. But I will still fight on. They can throw away the key – they probably did years ago. But I will go on. I’m a survivor, see.

Sometimes I think there is no way out, that I’m gonna destroy myself. They’re making me sick in the nut. And when I get bad heads, I’m unsafe, unstable. But I know I’m not a psychopath. I’ve lived with psychos; I know what makes them tick. I do have a conscience, and I do feel guilt. I’m deeper than any psycho. There are two sides to me. If I like a person, I’d die for them. If I hate them, they may die for me. Just pray you never get on my bad side. My bad side is your worst enemy.

But some days I get doubt, depression, anger. I feel isolated beyond anything you can imagine. HQ says I’m too dangerous to mix. Maybe I’ll end up like Rasputin, or Rudolph Hess.

Some nights I switch off, plug my ears and sit at my cardboard table under the security light … creating my art. I smile, I laugh, I feel happy. It may take one hour or ten hours. Who cares? But when I finish I feel drained, emotionally, physically, spiritually. It’s like giving birth to life. It is the one release I have from my inner self.

I’ve come a long way over the last five years and I am going to climb out of this stinking hole. I’m going to win. I owe it to my family and friends – and, most of all, to myself.

I don’t care if I face another 20 stinking years. I’ll do it. I’m a solitary fitness survivor. Once I’ve overcome my urges to tie people up, I’ll be a nice man on a mission of peace.

I’m going to walk out of whichever prison I’m in, in my black suit and shades, clean-shaven and ready for the start of my life on the outside.

I’ll walk away from that jail and not look back. And then all my loyal pals and I will go for a nice slice of apple pie and a cup of tea. We might have a sing-song. We’ll probably have a beer.

Then I’ll go to the coast and, if my bones are not too

creaky, I’ll run along the sea-front like I did during my 69 days of freedom back in 1987. They bet then that I would last only seven days. I proved them wrong.

I’ll prove them wrong again. Sooner or later I’m coming home. I am the ultimate survivor. One day the cell door and the gates will swing open and I’ll breathe again.

It’ll be a lovely day for a spot of bowls or a game of croquet!

Right now, I’ve gotta dash. Lots to do and only 20 years to do it in.

Stay lucky. And God bless!

Charles Bronson appeared at Luton Crown Court on February 14, 2000 and defended himself over the Hull siege. During a four-day trial he was found not guilty, on the judge’s direction, of causing Phil Danielson actual bodily harm, and also of a threat to kill. In evidence, Mr Danielson said Charlie had been ‘compassionate’ during the siege, making him cups of tea and giving him blankets.

Charlie pleaded not guilty to damaging prison property and false imprisonment, but on February 17 he was convicted unanimously by the jury. He’d argued he had been ‘under duress’ at the time of the hostage-taking, and gave an impassioned speech to the jury about his years of isolation. ‘When I wake up every morning I wake up with a headache from lack of air. Unnatural light. My eyes hurt. The first thing I do every morning when I wake up is go over to that window and stick my lips on the grille and suck in air. That’s how I get my air. Even the birds don’t come to Woodhill. The birds are frightened by Woodhill.’

After the guilty verdict, he was asked by the judge if he wanted to offer any mitigation. ‘Just crack on, give me some more porridge,’ he said.

Charlie was jailed for life. His earliest parole date is 2010. Before being led away to face more years of confinement, he said, ‘Why don’t you just shoot me?’