Brunelleschis Dome (16 page)

Read Brunelleschis Dome Online

Authors: Ross King

A century after its construction, the Florentine poet Giovanni Battista Strozzi described the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore as having been built

di giro in giro

, “circle by circle.” This expression no doubt alludes to the technique of bricklaying at Santa Maria del Fiore: the process of waiting for the mortar of one course of masonry to dry before laying another. But even allowing for metaphor and poetic license, it is still a slightly odd description if we consider that the dome is octagonal and not circular, a fact apparent to anyone who sees it. The difficulty in raising the dome lay in the fact that it was

not

circular. So what does Alberti mean when he speaks of a circular dome contained within the thickness of the polygonal one, or Strozzi when he says that the dome was built “circle by circle”?

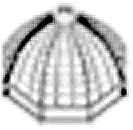

The herringbone brickwork, ingenious as it was, would not alone have been enough to stop the dome collapsing inward. Filippo’s real stroke of genius was in creating a kind of circular skeleton over which the external octagonal structure of the dome took shape. That is, the dome was constructed so that it contained within the thicknesses of its two shells a series of continuous circular rings. The inner shell of the cupola, as we have seen, is the thicker of the two, measuring between seven feet at its widest and five feet at its narrowest. With these dimensions it was large enough to incorporate into its center a complete circular vault roughly two and a half feet thick. Rowland Mainstone, the English structural engineer who determined this form following a survey in the mid-1970s, explains that the inner dome was constructed “as if it were a circular dome . . . but with parts cut away from both the inside and outside to leave the octagonal cloister-vault form.”

3

The herringbone bond was then used to secure the bricks that protruded forward of this circular ring — that is, those bricks on the inner shell that were not part of the horizontal ring.

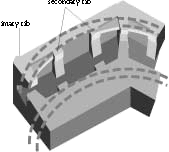

The outer shell posed a somewhat different dilemma. With a width of slightly more than two feet at its base, narrowing to just over a foot at the summit, it would not be possible to incorporate a circular vault within its thickness. How then could it, like the internal shell, be made self-supporting? The problem was a lesser one, in some respects, given that it might have been possible to support the masonry of the outer shell on the back of the inner one by using a small network of centering between the two. But this was not the solution adopted by Filippo.

A clue to the method used to build the outer shell in its upper levels can be found in the amendments made to the cupola project in 1426. As well as referring to the herringbone bond, these make reference to another brickwork construction, a horizontal arch that would be built on the inside of the dome’s outer shell: “Let bricks be built in the form of an arch for the perfection of the circle encompassing the outer shell, in order that this projecting arch may be complete and unbroken.” The purpose of this arch, the amendment states, was to make it possible “to bring the dome to completion with greater safety.”

Once built, this horizontal arch must have served its purpose, for in the end the masons built eight more of them, all continuous rings that form part of the octagonal structure of the outer shell. They were observed by the cupola’s first surveyor, Giovanni Battista Nelli, though their full Circle by Circle importance was not recognized until Mainstone’s much later survey. Each one is roughly 3 feet wide and 2 feet high, and they encircle the dome at 8-foot intervals, the first one being found just above the second sandstone chain. Visible in places from the internal walkways, they project at right angles from the inside of the outer shell, connecting the corner spurs to the intermediate ribs. Unlike the stone-and-iron chains, they are not intended to neutralize the lateral thrust, although it is possible that they transfer weight from the outer shell to the inner one.

4

They were a temporary measure, and if they appeared crude or obstructive, they were to be dismantled and removed once the dome was finished.

These nine rings served a vital function in building the cupola. They begin at the height — some 36

braccia

above the drum — above which the shell, curving inward, had passed beyond the critical angle of 30 degrees. This fact explains why the arch rings (like the herringbone courses, which serve a similar purpose) were begun at this level and not at a lower one, where the hoop tension is much greater. They are disposed round the circumference of the shell so that they thicken it at the corners, which would otherwise have interrupted what the 1426 amendment calls “the circle encompassing the outer shell,” ensuring that this circle is “complete and unbroken.” The masonry of the outer shell was thus rendered self-sufficient during the course of its construction and prevented from falling inward. Yet the rings are almost wholly disguised, being visible only in a few places between the two shells. From the outside the dome looks perfectly octagonal, as demanded by the 1367 model. Once again Filippo, the master of illusion, had exploited the difference between surface appearances and internal reality.

The nine horizontal circles within the dome.

A close-up of how the arch rings fit within two sides of the octagon.

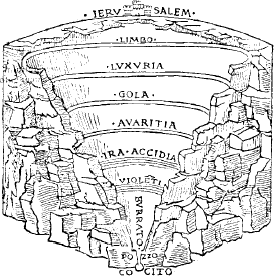

Giovanni Battista Strozzi’s description of the dome having been built “circle by circle” is not only a reference to the method of bricklaying or the series of ascending circles that compose the two shells. It is also an allusion to the

Divine Comedy

, where Dante uses this exact same phrase —

di giro in giro

— to describe paradise, which is envisioned as a series of nine concentric circles. The comparison of the dome to Dante’s paradise is an apt one for a number of reasons. Filippo was a scholar of Dante, having made an extensive study of the

Divine Comedy

in which his architectural instincts compelled him to calculate geometrically the precise dimensions of paradise; and domes have always been a conventional symbol of heaven. In both Eastern and Western art the ceilings of the most revered shelters have been associated with the heavens, visions of which have therefore often been executed on their surfaces in paintings or mosaics. Persian domes were said to express the flight of the soul from man to God.

5

But the nine arch rings built by Filippo in the outer shell of his dome recall nine other famous rings: those of Dante’s hell, which is composed of nine rings that descend conically into the earth, rather like an inverted dome. This too is an apt comparison, for in 1428, shortly after the first of the arch rings was completed, Filippo was to begin his own infernal descent.

HE

M

ONSTER OF THE

A

RNO

B

Y THE SPRING

of 1428 work on the cupola appeared to be progressing smoothly. The dome had risen more than 70 feet above the drum in less than eight years, and with the diameter now narrowing, it could be expected to ascend even more swiftly in the years to follow. But 1428 would be the year of Filippo’s first real setback since work on the dome had begun. His undoing was brought about by what must have seemed a minor problem in comparison with the ones he had already solved.

Over a hundred years earlier it had been decided that every inch of the exterior surface of Santa Maria del Fiore, with the exception of those parts tiled in brick, should be covered with marble. Marble was the typical building material of antiquity, but it had been used only sparingly in Florence, which was built, as we have seen, primarily from sandstone. Other than for his work on the cupola, Filippo would use no marble at all on his other buildings. Unlike sandstone, marble was scarce in the vicinity of Florence, and transporting it from afar without damaging it was difficult and onerous. Undaunted by these difficulties, the planners of Santa Maria del Fiore had ordered that three colors should encrust the cathedral: the greenish black stone known as

verde di Prato

; the red stone

marmum rubeum

; and, finally, a brittle white marble called

bianchi marmi

. This last stone would cover the eight enormous brick ribs of the cupola, and in June 1425 the Opera del Duomo signed a contract for 560 tons of it.

Bianchi marmi

was supplied from quarries near Carrara, 65 miles to the northwest of Florence. The marble from this remote district possesses a long and illustrious history. It was first exploited by the Romans, who used it for the Apollo Belvedere (which would be excavated at Frascati in 1455) and in the Arch of Constantine. Later Michelangelo would carve some of his most famous statues from it, including his

David

and the

Pietà

. In fact, Michelangelo spent a good many months of his life in the steep, dazzlingly white mountains around Carrara, reopening and inspecting old Roman quarries and fantasizing about carving gargantuan shapes into the hillsides.

Carrara marble was justifiably the most sought-after in Europe: hard, clean-breaking, and a chaste white, it was perfect for carving and ornamentation. It was also extremely expensive. Nevertheless, the Opera had been bringing this white marble to Florence for more than a hundred years, using it, for example, to clad Giotto’s campanile. In this enterprise the citizens of the Republic had been conscripted into service: in 1319 the Opera decreed that the people were to lend a helping hand whenever marble for the cathedral was shipped along the Arno. It was to be transported by those who operated small craft, primarily fishermen and the

renaiuoli

, men who scratched a meager living by harvesting gravel for the building trade from the Arno’s numerous sandbanks. This seems to have been an attempt on the part of the Opera to legislate for a sort of “Cult of the Carts” such as that seen during the twelfth century in France, where the population, gripped by a pious hysteria, helped to drag carts of stone from the quarries to the cathedrals.

The acquisition and working of marble from Carrara was a complex, delicate, and occasionally dangerous business. Extraction methods were similar to those for the sandstone at the Trassinaia quarry. Blocks of marble were first of all cut from their mountain beds by roughmasons wielding an array of tools: picks, hammers, crowbars, wedges, even heavy poleaxes to break the larger pieces. Besides brawn, the roughmason required a precise knowledge of the seams and an ability to cut both with and against the grain. After it was rough-hewn into shape, a more skilled artisan cut the stone to the exact size and shape specified by the templates. An even more varied assortment of tools, all of tempered iron, was used in carving the white marble, a stone notoriously difficult to work. A fine-pointed implement called the

subbia

chiseled the block to within an inch or two of the

penultima pelle

, or the second-last skin. Then a chisel with a notch in the center of the blade, the

scarpella

, was used, followed by the

lima raspa

, or roughing file, which came in a variety of shapes and thicknesses.