Bully for Brontosaurus (11 page)

Read Bully for Brontosaurus Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

We live in a profoundly nonintellectual culture, made all the worse by a passive hedonism abetted by the spread of wealth and its dissipation into countless electronic devices that impart the latest in entertainment and supposed information—all in short (and loud) doses of “easy listening.” The kiddie culture, or playground, version of this nonintellectualism can be even more strident and more one-dimensional, but the fault must lie entirely with adults—for our kids are only enhancing a role model read all too clearly.

I’m beginning to sound like an aging Miniver Cheevy, or like the chief reprobate on Ko-Ko’s little list “of society offenders who might well be underground”—and he means dead and buried, not romantically in opposition: “the idiot who praises with enthusiastic tone, all centuries but this and every country but his own.” I want to make an opposite and curiously optimistic point about our current mores: We are a profoundly nonintellectural culture, but we are not committed to this attitude; in fact, we are scarcely committed to anything. We may be the most labile culture in all history, capable of rapid and massive shifts of prevailing opinions, all imposed from above by concerted media effort. Passivity and nonintellectual judgment are the greatest spurs to such lability. Everything comes to us in fifteen-second sound bites and photo opportunities. All possibility for ambiguity—the most precious trait of any adequate analysis—is erased. He wins who looks best or shouts loudest. We are so fearful of making judgments ourselves that we must wait until the TV commentators have spoken before deciding whether Bush or Dukakis won the debate.

We are therefore maximally subject to imposition from above. Nonetheless, this dangerous trait can be subverted for good. A few years ago, in the wake of an unparalleled media blitz, drugs rose from insignificance to a strong number one on the list of serious American problems in that most mercurial court of public opinion as revealed by polling. Surely we can provoke the same immediate recognition for poor education. Talk about “wasted minds.” Which cause would you pick as the greater enemy, quantitatively speaking, in America: crack or lousy education abetted by conformity and peer pressure in an anti-intellectual culture?

We live in a capitalist economy, and I have no particular objection to honorable self-interest. We cannot hope to make the needed, drastic improvement in primary and secondary education without a dramatic restructuring of salaries. In my opinion, you cannot pay a good teacher enough money to recompense the value of talent applied to the education of young children. I teach an hour or two a day to tolerably well-behaved near-adults—and come home exhausted. By what possible argument are my services worth more in salary than those of a secondary-school teacher with six classes a day, little prestige, less support, massive problems of discipline, and a fundamental role in shaping minds. (In comparison, I only tinker with intellects already largely formed.) Why are salaries so low, and attendant prestige so limited, for the most important job in America? How can our priorities be so skewed that when we wish to raise the status of science teachers, we take the media route and try to place a member of the profession into orbit (with disastrous consequences, as it happened), rather than boosting salaries on earth? (The crisis in science teaching stems directly from this crucial issue of compensation. Science graduates can begin in a variety of industrial jobs at twice the salary of almost any teaching position; potential teachers in the arts and humanities often lack these well-paid alternatives and enter the public schools

faute de mieux

.)

We are now at a crux of opportunity, and the situation may not persist if we fail to exploit it. If I were king, I would believe Gorbachev, realize that the cold war is a happenstance of history—not a necessary and permanent state of world politics—make some agreements, slash the military budget, and use just a fraction of the savings to double the salary of every teacher in American public schools. I suspect that a shift in prestige, and the consequent attractiveness of teaching to those with excellence and talent, would follow.

I don’t regard these suggestions as pipe dreams, but having been born before yesterday, I don’t expect their immediate implementation either. I also acknowledge, of course, that reforms are not imposed from above without vast and coordinated efforts of lobbying and pressuring from below. Thus, as we work toward a larger and more coordinated solution, and as a small contribution to the people’s lobby, could we not immediately subvert more of the dinosaur craze from crass commercialism to educational value?

Dinosaur names can become the model for rote learning. Dinosaur facts and figures can inspire visceral interest and lead to greater wonder about science. Dinosaur theories and reconstructions can illustrate the rudiments of scientific reasoning. But I’d like to end with a more modest suggestion. Nothing makes me sadder than the peer pressure that enforces conformity and erases wonder. Countless Americans have been permanently deprived of the joys of singing because a thoughtless teacher once told them not to sing, but only to mouth the words at the school assembly because they were “off-key.” Once told, twice shy and perpetually fearful. Countless others had the light of intellectual wonder extinguished because a thoughtless and swaggering fellow student called them nerds on the playground. Don’t point to the obsessives—I was one—who will persist and succeed despite these petty cruelties of youth. For each of us, a hundred are lost—more timid and fearful, but just as capable. We must rage against the dying of the light—and although Dylan Thomas spoke of bodily death in his famous line, we may also apply his words to the extinction of wonder in the mind, by pressures of conformity in an anti-intellectual culture.

The

New York Times

, in an article on science education in Korea, interviewed a nine-year-old girl and inquired after her personal hero. She replied: Stephen Hawking. Believe me, I have absolutely nothing against Larry Bird or Michael Jordan, but wouldn’t it be lovely if even one American kid in 10,000 gave such an answer. The article went on to say that science whizzes are class heroes in Korean schools, not isolated and ostracized dweebs.

English wars may have been won on the playing fields of Eton, but American careers in science are destroyed on the playgrounds of Shady Oaks Elementary School. Can we not invoke dinosaur power to alleviate these unspoken tragedies? Can’t dinosaurs be the great levelers and integrators—the joint passion of the class rowdy and the class intellectual? I will know that we are on our way when the kid who names

Chasmosaurus

as his personal hero also earns the epithet of Mr. Cool.

Postscript

I had never made an explicit request of readers before, but I was really curious and couldn’t find the answer in my etymological books. Hence, my little parenthetical inquiry about

segue:

“Can anyone tell me how this fairly obscure Italian term from my musical education managed its recent entry into trendy American speech?” The question bugged me because two of my students, innocent alas (as most are these days) of classical music, use

segue

all the time, and I longed to know where they found it. Both simply considered

segue

as Ur-English when I asked, perhaps the very next word spoken by our ultimate forefather after his introductory, palindromic “Madam I’m Adam” (as in “segue into the garden with me, won’t you”).

I am profoundly touched and gratified. The responses came in waves and even yielded, I believe, an interesting resolution. (These letters also produced the salutary effect of reminding me how lamentably ignorant I am about a key element of American culture—pop music and its spin-offs.) I’ve always said to myself that I write these essays primarily for personal learning; this claim has now passed its own test.

One set of letters (more than two dozen) came from people in their twenties and thirties who had been (or in a case or two, still are) radio deejays for rock stations (a temporary job on a college radio station for most). They all report that

segue

is a standard term for the delicate task (once rather difficult in the days of records and turntables) of making an absolutely smooth transition, without any silence in between or words to cover the change, from one song to the next.

I was quite happy to accept this solution, but I then began to receive letters from old-timers in the radio and film business—all pointing to uses in the 1920s and 1930s (and identifying the lingo of rock deejays as a later transfer). David Emil wrote of his work in television during the mid-1960s:

The word was in usage as a noun and verb when I worked in the television production industry…. It was common for television producers to use the phrase to refer to connections between segments of television shows…. Interestingly, although I read a large number of scripts at this time, I never saw the word in writing or knew how it was spelled until the mid-1970s when I came across the word in a more traditional usage.

Bryant Mather, former curator of minerals at the Field Museum in Chicago, sent me an old mimeographed script of his sole appearance on radio—an NBC science show of 1940 entitled

How Do You Know

, and produced “as a public service feature by the Field Museum of Natural History in cooperation with the University Broadcasting Council.”

The script, which uses

segue

to describe all transitions between scenes in a dramatization of the history of the Orloff diamond, reminds us by its stereotyping and barely concealed racism (despite the academic credentials of its origin) that some improvements have been made in our attitudes toward human diversity. In one scene, for example, the diamond is bought by Isaacs, described as “a Jewish merchant.” His hectoring wife, called “Mama” by Mr. Isaacs, keeps pestering: “Buy it, Isaacs—you hear me—buy it.” Isaacs later sells to a shifty Persian, who cheats him by placing lead coins under the surface of gold in his treasure bag. Isaacs, discovering the trick, laments: “Counterfeit—lead—oi, oi, oi—Mama—we are ruined—we are ruined.” (Shades of Shylock—my ducats, my daughter.) The script’s next line reads “segue to music suggestive of Amsterdam or busy port.”

Page Gilman made the earliest link to radio and traced a most sensible transition (dare I say segue) between musical and modern media usages. I will accept his statement as our best resolution to date:

I think you may find that a bridge between the classical music to which you refer and today’s disk jockey use would be the many years of network radio. I began in 1927 and even the earliest scripts would occasionally use “segue” because we had a big staff of professional

working

musicians—people who worked (in those days) in restaurants, theaters (especially), and now radio. Today you’ll find a real corps of such folks only in New York and L.A.…. You’ll find me corroborated a little by Pauline Kael of the

New Yorker

, who remembers Horace Heidt’s orchestra at the Golden Gate Theater in San Francisco. That was the time when I was dating one of the Downey Sisters in the same orchestra. [May I also report the confirmation of my beloved 92-year-old Uncle Mordie of Rochester, New York, who relished his 1920s daily job in a movie orchestra, playing with the Wurlitzer during the silents and between shows—and never liked nearly as much his forty-year subsequent stint as lead violist in the Rochester Symphony.] I wonder if Bruce Springsteen ever heard of “segue.” On such uncultured times have working musicians fallen.

This tracing of origins does not solve the more immediate problem of recent infiltration into general trendy speech. But perhaps this is not even an issue in our media-centered world, where any jargon of the industry stands poised to break out. Among many suggestions for this end of the tale, several readers report that Johnny Carson has prominently used

segue

during the past few years—and I doubt that we would need much more to effect a general spread.

Finally, on my more general inquiry into the sources of our current dinomania, I can’t even begin to chronicle the interesting suggestions for fear of composing another book. Just one wistful observation for now. Last year, riding a bus down Haight Street in San Francisco, I approached the junction with Ashbury eager to see what businesses now occupied the former symbolic and actual center of American counterculture. Would you believe that just three or four stores down from the junction itself stands one of those stores that peddles nothing but reptilian paraphernalia and always seems to bear the now-clichéd name “Dinostore.” What did Tennyson say in the

Idylls of the King?

The old order changeth, yielding

place to new;

And God fulfills himself in

many ways,

Lest one good custom should corrupt

the world.

LIKE OZYMANDIAS

, once king of kings but now two legs of a broken statue in Percy Shelley’s desert, the great façade of Union Station in Washington, D.C., stands forlorn (but ready to front for a bevy of yuppie emporia now under construction), while Amtrak now operates from a dingy outpost at the side.

*

Six statues, portraying the greatest of human arts and inventions, grace its parapet. Electricity holds a bar of lightning; his inscription proclaims: “Carrier of light and power. Devourer of time and space…. Greatest servant of man…. Thou hast put all things under his feet.”

Yet I will cast my vote for the Polynesian double canoe, constructed entirely with stone adzes, as the greatest invention for devouring time and space in all human history. These vessels provided sufficient stability for long sea voyages. The Polynesian people, without compass or sextant, but with unparalleled understanding of stars, waves, and currents, navigated these canoes to colonize the greatest emptiness of our earth, the “Polynesian triangle,” stretching from New Zealand to Hawaii to Easter Island at its vertices. Polynesians sailed forth into the open Pacific more than a thousand years before Western navigators dared to leave the coastline of Africa and make a beeline across open water from the Guinea coast to the Cape of Good Hope.

New Zealand, southwestern outpost of Polynesian migrations, is so isolated that not a single mammal (other than bats and seals with their obvious means of transport) managed to intrude. New Zealand was a world of birds, dominated by several species (thirteen to twenty-two by various taxonomic reckonings) of large, flightless moas. Only

Aepyornis

, the extinct elephant bird of Madagascar, ever surpassed the largest moa,

Dinornis maximus

, in weight. Ornithologist Dean Amadon estimated the average weight of

D. maximus

at 520 pounds (although some recent revisions nearly double this bulk), compared with about 220 pounds for ostriches, the largest living birds.

We must cast aside the myths of noble non-Westerners living in ecological harmony with their potential quarries. The ancestors of New Zealand’s Maori people based a culture on hunting moas, but soon made short work of them, both by direct removal and by burning of habitat to clear areas for agriculture. Who could resist a 500-pound chicken?

Only one species of New Zealand ratite has survived. (Ratites are a closely related group of flightless ground birds, including moas, African ostriches, South American rheas, and Australian-New Guinean emus and cassowaries. Flying birds have a keeled breastbone, providing sufficient area for attachment of massive flight muscles. The breastbones of ratites lack a keel, and their name honors that most venerable of unkeeled vessels, the raft, or

ratis

in Latin.) We know this curious creature more as an icon on tins of shoe polish or as the moniker for New Zealand’s human inhabitants—the kiwi, only hen-sized, but related most closely to moas among birds.

Three species of kiwis inhabit New Zealand today, all members of the genus

Apteryx

(literally, wingless). Kiwis lack an external tail, and their vestigial wings are entirely hidden beneath a curious plumage—shaggy, more like fur than feathers, and similar in structure to the juvenile down of most other birds. (Maori artisans used kiwi feathers to make the beautiful cloaks once worn by chiefs; but the small, secretive, and widely ranging nocturnal kiwis managed to escape the fate of their larger moa relatives.)

The furry bodies, with even contours unbroken by tail or wings, are mounted on stout legs—giving the impression of a double blob (small head and larger body) on sticks. Kiwis eat seeds, berries, and other parts of plants, but they favor earthworms. Their long, thin bills probe the soil continually, suggesting the oddly reversed perspective of a stick leading a blind man. This stick, however, is richly endowed as a sensory device, particularly as an organ of smell. The bill, uniquely among birds, bears long external nostrils, while the olfactory bulb of kiwi brains is second largest among birds relative to size of the forebrain. A peculiar creature indeed.

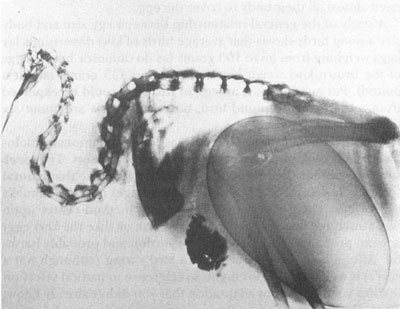

An amazing and famous photo of a female kiwi one day before laying its enormous egg.

COURTESY OF THE OTOROHANGA ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY, NEW ZEALAND

.

But the greatest of kiwi oddities centers upon reproduction. Females are larger than males. They lay one to three eggs and may incubate them for a while, but they leave the nest soon thereafter, relegating to males the primary task of incubation, a long seventy to eighty-four days. Males sit athwart the egg, body at a slight angle and bill stretched out along the ground. Females may return occasionally with food, but males must usually fend for themselves, covering both eggs and nest entrance with debris and going forth to forage once or twice on most nights.

The kiwi egg is a wonder to behold, and the subject of this essay. It is, by far, the largest of all bird eggs relative to body size. The three species of kiwis just about span the range of domestic poultry: the largest about the size of Rhode Island Reds; the smallest similar to bantams—say five pounds as a rough average (pretty meaningless, given the diversity of species, but setting the general domain). The eggs range to 25 percent of the female’s body weight—quite a feat when you consider that she often lays two, and sometimes three, in a clutch, spacing them about thirty-three days apart. A famous X-ray photo of kiwi and egg taken at the kiwi sanctuary of Otorohanga, New Zealand, tells the tale more dramatically than any words I could produce. The egg is so large that females must waddle, legs spread far apart, for several days before laying, as the egg passes down the oviduct toward the cloaca. The incubation patch of male kiwis extends from the top of the chest all the way down to the cloaca—in other words, they need almost all their body to cover the egg.

A study of the general relationship between egg size and body size among birds shows that average birds of kiwi dimensions lay eggs weighing from 55 to 100 grams (as do domestic hens). Eggs of the brown kiwi weigh between 400 and 435 grams (about a pound). Put another way, an egg of this size would be expected from a twenty-eight-pound bird, but brown kiwis are about six times as small.

The obvious question, of course, is why? Evolutionary biologists have a traditional approach to riddles of this sort. They seek some benefit for the feature in question, then argue that natural selection has worked to build these advantages into the animal’s way of life. The greatest triumphs of this method center upon odd structures that seem to make no sense or (like the kiwi egg) appear, prima facie, to be out of proportion and probably harmful. After all, anyone can see that a bird’s wing (although not a kiwi’s) is well designed for flight, so reference to natural selection teaches you little about adaptation that you didn’t already know. Thus, the test cases of textbooks are apparently harmful structures that, on closer examination, confer crucial benefits upon organisms in their Darwinian struggle for reproductive success.

This general strategy of research suggests that if you can find out what a structure is good for, you will possess the major ingredient for understanding why it is so big, so colorful, so peculiarly shaped. Kiwi eggs should illustrate this basic method. They seem to be too big, but if we can discover how their large size benefits kiwis, we shall understand why natural selection favored large eggs. Readers who have followed my essays for some time will realize that I wouldn’t be writing about this subject if I didn’t think that this style of Darwinian reasoning embodied a crucial flaw.

The flaw lies not with the claim of utility. I regard it as proved that kiwis benefit from the unusually large size of their eggs—and for the most obvious reason. Large eggs yield large and well-developed chicks that can fend for themselves with a minimum of parental care after hatching. Kiwi eggs are not only large; they are also the most nutritious of all bird eggs for a reason beyond their maximal bulk: they contain a higher percentage of yolk than any-other egg. Brian Reid and G. R. Williams report that kiwi eggs may contain 61 percent yolk and 39 percent albumin (or white). By comparison, eggs of other so-called precocial species (with downy young hatching in an active, advanced, and open-eyed state) contain 35 to 45 percent yolk, while eggs of altricial species (with helpless, blind, and naked hatchlings) carry only 13 to 28 percent yolk.

The lifestyle of kiwi hatchlings demonstrates the benefits of their large, yolky eggs. Kiwis are born fully feathered and usually receive no food from their parents. Before hatching, they consume the unused portion of their massive yolk reserve and do not feed (but live off these egg-based supplies) for their first seventy-two to eighty-four hours alfresco. Newly hatched brown kiwi chicks are often unable to stand because their abdomens are so distended with this reserve of yolk. They rest on the ground, legs splayed out to the side, and only take a first few clumsy steps when they are some sixty hours old. A chick does not leave its burrow until the fifth to ninth day when, accompanied by father, it sallies forth to feed sparingly.

Kiwis thus spend their first two weeks largely living off the yolk supply that their immense egg has provided. After ten to fourteen days, the kiwi chick may weigh one-third less than at hatching—a fasting marked by absorption of ingested yolk from the egg. Brian Reid studied a chick that died a few hours after hatching. Almost half its weight consisted of food reserves—112 grams of yolk and 43 grams of body fat in a 319-gram hatchling. Another chick, killed outside its burrow five to six days after hatching, weighed 281 grams and still held almost 54 grams of enclosed yolk.

I am satisfied that kiwis do very well by and with their large eggs. But can we conclude that the outsized egg was built by natural selection in the light of these benefits? This assumption—the easy slide from current function to reason for origin—is, to my mind, the most serious and widespread fallacy of my profession, for this false inference supports hundreds of conventional tales about pathways of evolution. I like to identify this error of reasoning with a phrase that ought to become a motto:

Current utility may not be equated with historical origin

, or, when you demonstrate that something works well, you have not solved the problem of how, when, or why it arose.

I propose a simple reason for labeling an automatic inference from current utility to historical origin as fallacious: Good function has an alternative interpretation. A structure now useful may have been built by natural selection for its current purpose (I do not deny that the inference often holds), but the structure may also have developed for another reason (or for no particular functional reason at all) and then been co-opted for its present use. The giraffe’s neck either got long in order to feed on succulent leaves atop acacia trees or it elongated for a different reason (perhaps unrelated to any adaptation of feeding), and giraffes then discovered that, by virtue of their new height, they could reach some delicious morsels. The simple good fit of form to function—long neck to top leaves—permits, in itself, no conclusion about why giraffes developed long necks. Since Voltaire understood the foibles of human reason so well, he allowed the venerable Dr. Pangloss to illustrate this fallacy in a solemn pronouncement:

Things cannot be other than they are…. Everything is made for the best purpose. Our noses were made to carry spectacles, so we have spectacles. Legs were clearly intended for breeches, and we wear them.

This error of sliding too easily between current use and historical origin is by no means a problem for Darwinian biologists alone, although our faults have been most prominent and unexamined. This procedure of false inference pervades all fields that try to infer history from our present world. My favorite current example is a particularly ludicrous interpretation of the so-called anthropic principle in cosmology. Many physicists have pointed out—and I fully accept their analysis—that life on earth fits intricately with physical laws regulating the universe, in the sense that were various laws even slightly different, molecules of the proper composition and planets with the right properties could never have arisen—and we would not be here. From this analysis, a few thinkers have drawn the wildly invalid inference that human evolution is therefore prefigured in the ancient design of the cosmos—that the universe, in Freeman Dyson’s words, must have known we were coming. But the current fit of human life to physical laws permits no conclusion about the reasons and mechanisms of our origin. Since we are here, we have to fit; we wouldn’t be here if we didn’t—though something else would, probably proclaiming, with all the hubris that a diproton might muster, that the cosmos must have been created with its later appearance in mind. (Diprotons are a prominent candidate for the highest bit of chemistry in another conceivable universe.)

But back to kiwi eggs. Most literature has fallen into the fallacy of equating current use with historical origin, and has defined the problem as explaining why the kiwi’s egg should have been actively enlarged from an ancestor with an egg more suited to the expectations of its body size. Yet University of Arizona biologist William A. Calder III, author of several excellent studies on kiwi energetics (see 1978, 1979, and 1984 in the bibliography), has proposed an opposite interpretation that strikes me as much more likely (though I think he has missed two or three good arguments for its support, and I shall try to supply them here).