Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (33 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

We would rather be unique than equal

There was a kingdom called Andher Nagari, literally meaning the dark land, where everything cost just one rupee. A measure of vegetables cost a rupee, the same measure of sweets also cost a rupee. A young man thought this place was paradise. "No, it is not," said his teacher, "A country where there is no differentiation between vegetables and sweets is a dangerous place. Just run from here." But the young man insists on staying back, enjoying the delights of the market.

It so happened that in this kingdom a murderer had to be hanged for his crime. Unfortunately, the rope was too short and the noose too wide to hang the short, thin criminal. So Chaupat Raja, the insane king of Andher Nagari, said, "Find a tall and fat man who can be hanged instead. Someone has to be hanged for the crime." The soldiers catch the young man in the market. He protested that he is no murderer. "But you are tall and fat enough to be hanged," said the king. It is then the young man realized what his teacher had been trying to tell him: that the people who could not differentiate between vegetables and sweets, where everything was valued equally and cost the same, in their eyes there was no difference between a criminal and an innocent man.

This folk story speaks of a land where everyone is treated equally. No value is placed on differences. Only humans can imagine such a world. In nature, physical differences matter. This difference results in food chains and pecking orders. Humans can, if they so will, create a world where no differences are seen. Such a utopia is frightening as it means in this world nothing is special, no one matters, no one is significant.

The head office prepared a design and insisted that every office of the company around the world be designed accordingly. They were essentially open offices, with no cabins for individuals, but with rooms for meetings and teleconferences. The point was to express the organizational value of transparency and equality. Instead of energizing the workplace, the new design demotivated many. Shridhar suddenly found himself without a cabin. All his life he had worked to become worthy of a cabin and now the policy had changed. He felt angry and humiliated. He felt he had been denied his Durga. He did not matter. He was a nobody like everyone else. As soon as he got a job in a rival firm, with the assurance of a cabin, he left. At the exit interview, the human resource manager felt that he was being immature: how did a cabin matter? Clearly what mattered to the manager was very different from what mattered to Shridhar, who did not want to be part of Andher Nagari.

Culture provides only a temporary framework for our social body

In the Ramayan, as Dashrath, king of Ayodhya, is dying, he panics and calls his wife and says, "I am dying. My eldest son, Ram, has been exiled to the forest. My other son, Bharat, has not yet returned from his uncle's house. I cannot afford to die. What will happen to Ayodhya if I am not there." To this, his wife says, "Nothing will happen. The sun will rise, and set. The moon will wax and wane. People will go about their business. Ayodhya will survive, perhaps not even noticing the absence of its king."

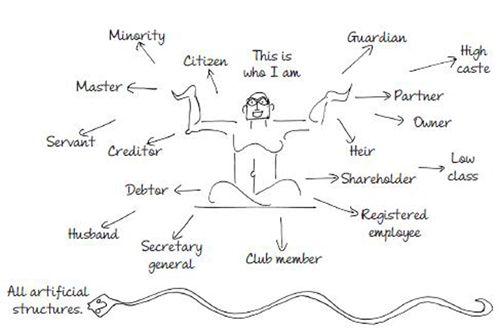

It is Ayodhya that makes Dasharath feel he matters. If there were no Ayodhya, he would not be king and his death would have no grave significance. Organizations grant us value. They position us both within the organization as well as outside. What we fail to realize is that while we need the organization, the organization does not need us. Brahma needs sanskriti to escape the indifference of prakriti but sanskriti does not need Brahma.

Every day, organizations hire new people and old people leave the company—either angrily, or happily, or because they have no choice. This is the 'birth' of a new employee and the 'death' of an old one. Both events are filled with insecurity. The arrival of a new employee threatens the old discourse, and so there is need to induct the new into the old ways of the company. The departure of the old employee also threatens the old discourse hence the desperate need for a talent pool and pipeline. Very rarely does an individual become indispensable to a degree that determines the fate of an institution. There is always someone who can take his place. The denial of this truism leads to panic. Acceptance leads to peace.

Pathakji had served the company as an accountant for over thirty-eight years. He was so good at managing the accounts that the owner felt he was indispensable. So did Pathakji, until one day, the owner died and his nephew took over. The nephew did not think much of Pathakji. He was given a nice salary and a nice cabin but no real work. Pathakji was furious and soon after submitted his resignation in a huff; this was accepted without even the pretence of resistance. "Let me see how they solve the accounts," he said as he left the building for the last time. Five years have since passed. Pathakji is still waiting for the new management to call him back. They are managing without him. It's a feeling he does not like. The management did suffer for a while without Pathakji, but his absence created a vacuum and new talent emerged. That was a good thing. But now that apparently indispensable Pathakji has been replaced, those left behind in the company feel they, too, are dispensable. It is a feeling no one likes. Suddenly, they all feel like 'full time equivalents' or FTEs, numbers on an excel sheet that can be deleted at any moment. Insecurity seeps into the organization. And in insecurity, everybody clings to their respective roles and responsibilities with tenacity. New talent is not allowed to come in and if they do come in they are not allowed to thrive. Everyone wants to make themselves indispensible. They will all die trying.

Property

Property is an idea of man, by man, and for man. Property gives a man value, for most people assume we are what we have because what we have is tangible, not who we are. We may die, but what we have can outlive us. Thus property gives us the delusion of immortality.

We see things not thoughts

When they decided to go to war, both the Kauravs and the Pandavs approached Krishna for help. "I love you both equally so will divide myself into two halves. Take whichever half you want."

Krishna offered one side the Narayani Sena, his fully-armed army. To the other, he offered Narayan, that is, himself unarmed. The Kauravs chose Narayani Sena. The Pandavs chose Narayan. The Kauravs chose Krishna's resources that are saguna: visible, tangible and measurable while the Pandavs chose Krishna's potential or nirguna: invisible, intangible and not measurable.

Narayan is who-we-are. Narayani is what-we-have. Narayan is expressed through Narayani. Most people rely on measuring Narayani to determine what is Narayan.

That is how the value of a person is determined by his possessions: his university degrees, income, bank balance, clothes, car, and so on.

Possessions are resources. They are tangible and measurable. Potential is not tangible and measurable. In the world of management where measurement matters, Narayan is ignored and Narayani preferred. We check what a person brings to the table during interviews. We value a customer's wallet, more than the customer. A employee is valued for his skills only. His vision, his fears, his feelings do not matter. The latter cannot be measured. Their value cannot be determined. Nobody knows how to leverage who we are. But we have many ways of leveraging what-we-have. In other words, we welcome Kauravs into the organization, not Pandavs, which does not bode well for anyone.

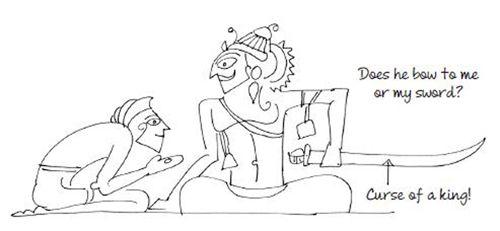

Every leader wonders if the person speaking to him speaks to his person or the authority he wields by virtue of his position. The king wonders if he matters or his sword: this is the curse of kingship.

To motivate his team, Bipin asked his guru to give them a speech. The guru quoted verses from the Bhagavad Gita about staying calm in success and in failure. While it felt good to hear the discourse, one of Bipin's sales managers was heard commenting, "I may be calm but my failure will certainly get Bipin agitated. He does not care for us. He only cares for our performance. We are a performance-driven organization after all." The sales manager knew that if his sales numbers dipped, he could bid his bonus goodbye. The company only cared for the Narayani, not the Narayan.

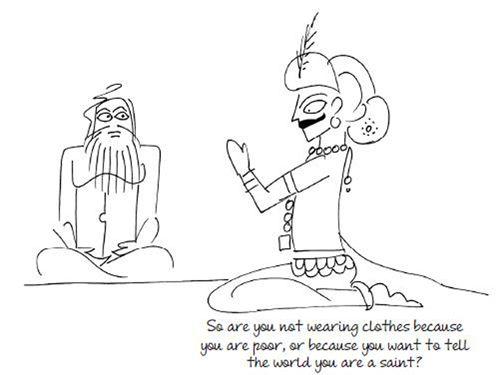

Things help us position ourselves

When Hanuman, a monkey, entered Lanka and identified himself as Ram's messenger and asked for a seat as protocol demanded, he was spurned by the rakshasa-king, Ravan, who insulted him by denying him one. Hanuman retaliated by announcing that he would create a seat for himself: he extended his tale, coiled it around and created a seat higher than Ravan's throne. Instead of being amused or impressed, Ravan was infuriated. His power was threatened. In a rage, he ordered Hanuman's tail be set aflame.

The story reveals how a thing (a seat) is used to communicate a thought (pecking order). Hanuman does not care for power or for thrones but he realizes things mean a lot to Ravan. By the dramatic use of his tail, he breaches the fortress of Ravan's mind and shatters his mental image in an instant.

What is interesting is that Hanuman does not need an external thing to position himself; he expands what he already has—his tail. In other words, he finds strength within and does not need the help of an object or a salutation. He has enough Shakti to compensate for the Durga that Ravan refuses to give him.

We constantly use material things to position ourselves: our cabins, our houses, our cars, our mobile phones, and so on. When these are taken away from us, or damaged, we feel hurt. When our possessions are damaged, when our car gets scratched, or our watch gets stolen, or our seat is given to someone else, our social body gets damaged and this causes pain to the mental body; even though the physical body is perfectly fine.

When it was time to buy a new mobile phone, Pervez had a simple rule. He checked what models his clients and his bosses were using. He then bought an inferior model. He did not want to intimidate any of them or make them feel insecure. In fact, he wanted them to criticize his choice and mock him for buying a poor-quality phone. "I want them to put me down. I want them to feel superior. It helps me in my relationship with them." Pervez has understood the power of using things to generate Durga.