Buttons (8 page)

A selection of nineteenth- and twentieth-century pressed black glass. Note that the top right button has a pattern resembling shot taffeta, a fabric very popular at the time.

Silver-lustred black glass. Notice how closely the two largest buttons on the top row resemble the cut steel and court-dress buttons shown on pages

23

and

24

.

Nineteenth-century glass buttons. (Top row, left to right) Painted milky glass; red ball with overset glass ribbons; pink glass with Venetian-style gold glass applied to the surface. (Second row) Milky glass with added lustre. (Third row) White glass with moulded red and clear glass flower; clear glass with blue reverse paint. (Fourth row) Clear glass with lustred centre and reverse-painted intaglio design of roses. (Fifth row) Ball of wound glass strands; mottled pink glass with added centre of glass imitation gold stone. (Sixth row) Clear glass with reverse mirror paint and top lustring resembling cut steel. (Seventh row) Cut steel studs mounted in black glass; black glass ball with inlaid white decoration.

Cloth-covered

buttons are the simplest type of shanked button possible. The cloth is placed over a core of wound wool or wood, stitched in place, and held to the garment with more stitches. This basic construction has been used for centuries, adapted to reflect the fashion of the period. Machinery to make cloth-covered metal buttons was introduced at the beginning of the nineteenth century, a patent being taken out by Benjamin Sanders after he perfected the process in 1825. Large-scale handwork had ceased by 1850 with the introduction of more efficient machinery. Towards the end of the century very small hand-operated machines were introduced so that each tailoring establishment could make its own covered buttons. Such was the constancy of the fashion for cloth buttons that cloth designs were reproduced on buttons of many different materials.

Glass

was used to cover delicate decorations on the eighteenth-century dandies’ buttons. In the nineteenth century Paisley and other designs were produced on the reverse of a mounted dome of glass, offering some protection to the paint. Into the twentieth century a three-dimensional effect was achieved by impressing an image into the base of a mounted dome of glass, intaglio style, and reverse-painting the detail.

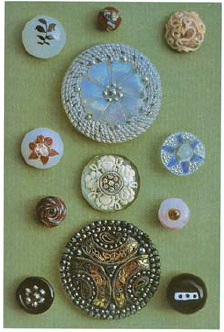

Nineteenth- and twentieth-century glass buttons. (Top row, left to right) Moulded glass reverse-painted to create kaleidoscopic effect; grey owVs head with reverse-painted domed eyes; pressed white glass with paint adding definition to the picture; white bird hand-painted on black glass; pearl disc inset into blue glass. (Middle row, left to right) Moulded milky glass with painted raised head; micro-mosaic in black glass, mounted in metal; glass beads glued into green glass base; pearlised glass bead attached to black glass base, mounted in metal; moulded white glass with raised lustred dragon. (Bottom row, left to right) Black glass with hardstone inlay; glass resembling moonstone inlaid into milky glass; black glass with white-painted flowers; moulded white glass deer with painted background; black glass with painted decoration; painted orange glass with inset milky glass centre; moulded white glass centre, resembling carved ivory, set into black glass.

The nineteenth-century vogue for fancy buttons on women’s clothing prompted very inventive uses of glass, with metal shanks through which to thread the fixing clips and rings. With no effective trades description legislation, black glass was sold described as jet, or French jet, which has led to confusion. Few real jet buttons were made as the material was not sufficiently robust for the purpose. Metal shanks were still in use in the twentieth century but had largely given way to the self-shank. The predominance of glass as a material for buttons ended with the advent of durable unbreakable plastics.

The eternally classic diamante buttons can be dated only by close examination of the style of diamante and the material and construction of its setting.

Decorated glass buttons should not be immersed in water for cleaning as any paint or lustre will be removed and any glue weakened.

Hardstones

were made into buttons by jewellers by mounting, or drilling and fitting a shank. Precise dating is difficult as any jeweller could produce a gemstone button, but they were particularly fashionable as part of the gift trade at the end of the nineteenth century. Glassmakers produced imitation stones with great expertise, but look for polish markings and transversed fault lines on gemstones, contrasting with the uniformity of size and colour and, possibly, mould markings on glass.

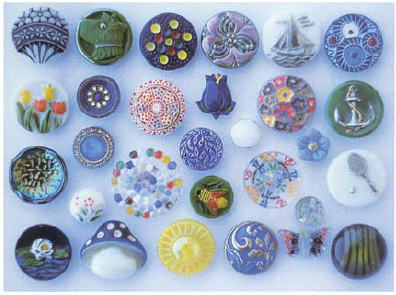

Twentieth-century glass, painted moulded self-shank.

Diamante buttons, all twentieth-century except as detailed. (Top row, left to right) Flat-set into stamped base; set in silver; set in spelter; set in silver; claw set on frame. (Middle row, left to right) Shoe button; set into glass; nineteenth-century, set in hand-worked silver; set into glass; shoe button. (Bottom row, left to right) Claw-set with a brass trim; nineteenth-century claw-set with riveted steel trim; flat-set in metal.

Hardstone buttons. (Centre) Moss agate. (Outer ring, large) Cornelian with silver pin shank. (Outer ring, small) Turquoise tesserae set in silver.

Metal buttons mounted with various pieces of coloured glass made to imitate hardstones, nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century.

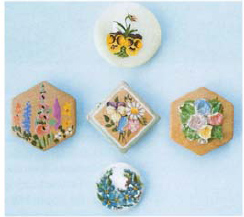

Home-decorated buttons. (Top row) Transfer on shell. (Middle row, left to right) Two of hand-painted wood; barbola work on wood. (Bottom row) Hand-painted on shell.