Buttons (6 page)

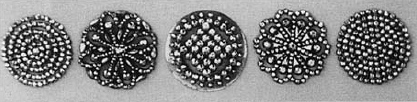

Cut steel buttons from the eighteenth century, individually polished and riveted to cut plates.

Enamel

can be added to most rigid metals but in button-making it is generally brass or silver. The technique involves firing powdered glass on to the base and has been used in decorating buttons for centuries. Few eighteenth-century enamels are available to collectors but nineteenth- and twentieth-century examples can be found – mostly

champleve

or

basse taille

(or

guilloche)

enamelling.

Galvanising

denotes the process of plating zinc on to iron or steel to prevent rust. It was not perfected until the middle of the nineteenth century and became more widely available by the end of the century, when it came into use for button backs.

Traditional court-dress buttons.

Enamel on silver by Liberty, all marked ‘1902 Birmingham, L & Co. Cymric’.

Nineteenth- and twentieth-century enamel buttons.

Golden age buttons marked ‘Treble Standard MS&JD’.

Golden age buttons, with various back marks such as ‘Treble Standard’ or ‘Extra Treble Standard’, indicating compliance with the 1796 Act of Parliament.

A selection of twentieth-century painted metal buttons, some with added celluloid decoration.

These metal buttons are painted to closely resemble enamelled buttons. The fourth from the left has a celluloid inset with painted trim.

Gilding

was practised for many years, coming to high fashion towards the end of the eighteenth century when fraudulent practices were threatening the trade. In 1796 an Act of Parliament was passed laying down specific standards for gilt buttons. The fashion for these gentlemen’s buttons continued to the middle of the nineteenth century. They are known by collectors as ‘golden age’ buttons.

Japanned

is a term used to describe the hard, usually black, paint which acted as a substitute for the oriental lacquering. Each coat was dried, either naturally or with heat, and further coats were added, making a thick layer. Its protective, hard-wearing qualities made it ideal for use on the backs of metal buttons, particularly at the end of the nineteenth century.

Paint

has been added to metals in many guises but is easily removed by wear and washing. This unfired type of decoration does not have the glassy shine of enamel and does not form such a thick layer but, confusingly, can be referred to as ‘cold enamel’.

Silver plating

was discovered in 1742 by Thomas Bolsover when he found that molten silver would fuse on to copper. It made an easily worked substitute for silver. Buttons were amongst the trinkets he produced from the material. Later in the eighteenth century the discovery was fully exploited by Sheffield manufacturers, hence the term ‘Sheffield plate’. To identify it, look with a magnifying glass on worn edges of the button for two distinct layers of metal. Electroplating, patented in 1840, produced a wash-thin layer of silver with no distinct join to the base metal.

As buttons have such a small surface area it is difficult to identify some materials. The necessary tests with chemicals or hot needles could well damage the button. Late-twentieth-century washing liquids and powders are chemically very different from the products in use earlier in the century. If it is necessary to use more than just a cloth to clean a plain non-metal button, use an appropriate product for the material. Natural plastics, bone, nut, ivory or wood respond well to a waxy furniture polish, but care must be taken not to remove patina or decoration.

Bakelite,

introduced in 1907, is the earliest of the man-made plastics in use in button-making.

Bone

was the staple material used to make the utilitarian sew-through buttons for underwear. It was also used as a base for decorative work and in a carved form with a metal loop shank. With a pinhead shank, it was used to make overall buttons and, because of its strength and resistance to salt water and most chemicals, this type continued to be made until the early 1960s. A natural black vegetable dye was effective on bone but otherwise it would not readily take colouring. Most commonly the dense surface of the leg bone, closely resembling ivory, was used. Look on the back of the button for straight, parallel grain lines and the minute grooves that carried the blood vessels. They appear in cross-section as tiny holes.

Casein,

a natural plastic made from curdled milk, was developed in the 1890s. The original formula would not take fast dyes, and sunlight caused fading and cracking. The material, much improved, was in wide use by the 1930s and production continued until the 1970s.

Celluloid,

a natural plastic developed from wood flour or cotton fibre, was patented in 1869. At the end of the nineteenth century it was used only sparingly as part of the decoration of buttons, owing to its expense. By the early twentieth century, with cheaper production methods, it was used to form an entire covering of metal-backed buttons. Its vogue did not last long as it was highly inflammable.

Bakelite buttons.