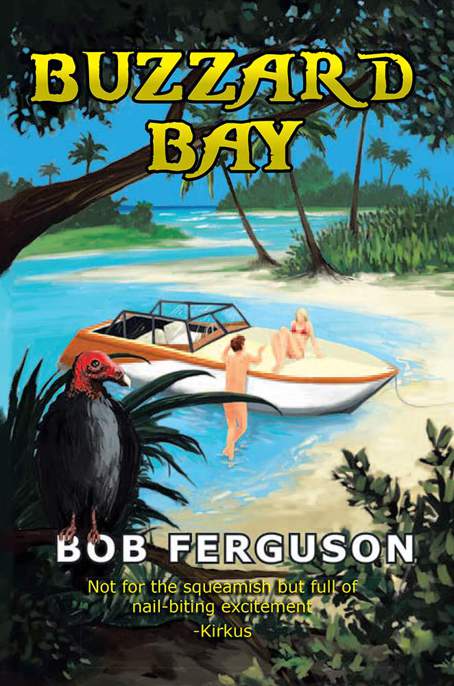

Buzzard Bay

Authors: Bob Ferguson

BUZZARD BAY

BOB FERGUSON

Copyright © 2012 by .

Library of Congress Control Number: | 2012909843 | |

ISBN: | Hardcover | 978-1-4771-2209-9 |

oftcover | 978-1-4771-2208-2 | |

Ebook | 978-1-4771-2210-5 |

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to any actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Rev. date: 07/03/2013

To order additional copies of this book, contact:

Xlibris Corporation

1-888-795-4274

107439

CONTENTS

White Powder

There’s a sayin in the islands an that sayin say

If you want to go on livin, stay away from Buzzard Bay

But if you be tired of what livin’s givin an you want to make your play

Then that’s where you be goin boy, down on Buzzard Bay

Chorus

White cocaine like acid rain

In the nose down to your toes an settles in your brain

I’s just the boy who loads the boat and set it afloat

o the coke can go explore some foreign shore

Where it begins by creepin in under your neighbor’s door

Even on to the New York tradin floor where the man knows he has to score

o tonight he can buy some more of the yeah, you got it, white powder

Chorus

There’s a storm of white sand movin north across the Rio Grande

Where the man tried to make a stand but that didn’t even slow the flow

Of that blow comin up from Mexico

Ran right over the Alamo, turned to snow when it hit Idaho

Decided to give the west coast a tease, got caught up in an L.A. breeze

An went across the seas to visit the Chinese

Left a smog in the air over Tiananmen Square, then went to see the Russian bear

Jumped right over the Kremlin gate, spent the night on a fashionable English estate

An at daybreak ended up on some Arab’s breakfast plate

Chorus

Yeah, that white powder it don’t discriminate, it don’t care how much you make

It don’t give, it just take everything that man can create

White cocaine like acid rain, I got a woman on the brain

I’s the man who loads the boat but that don’t keep me afloat

My woman wants to be a star when she walks into the bar, even wants a new car

o I do a little stealin, do a little dealin, just to keep her by my side

Now the man’s comin to take me for a ride, that woman of mine never even cried

When they found me washed up in the mornin tide

he never missed a beat, wasn’t even discreet

When she asked that man on the next barstool seat

If she could give him a little treat

For some of that, yeah, you know, white powder

Chorus

It don’t pick, it don’t choose

It don’t care if you win or lose

It’s just there for you to use

Yeah, you know, the white powder

I dedicate this book to my wife Irene, who is my editor, mentor and love of my life.

Without her this book would never have been written.

1997

L

IKE THE SHOCK

of an electrical wire, my every sense becomes alert. Instantly, I’m awake, searching to understand what it was that startled me from that deep sleep. Someone’s in the house, or is it just the house cracking and shrinking from the intense cold outside? Silence. Only the ticking of Mom’s old mantle clock breaks the intensity of the moment. A feeling of fear begins to invade my senses; something’s not right.

I quickly scramble from the old feather tick. Panic grips, my heart’s in my mouth, and I feel like running. But where? How? Deep breaths; get a hold of yourself. Maybe it’s nothing, yet something’s not right. What? Slow now, think… you know you’ve been worried about something, and you know what that is, so confirm your suspicions. I don’t think what’s troubling me is in the house, at least not yet, so check out the house.

The panic is subsiding; cold calculation is setting in as I throw on my pants and shirt. I know downstairs, Dad’s gun case is hanging on the living room wall. What am I saying? It’s probably nothing. Much more confident, I slip downstairs.

The moonlight shining off the snow illuminates the living room, giving me no problems finding my way around as I quietly check out the house. It’s out the back kitchen window that I see them. Christ! There they are, right outside the window, three of them. I’m so scared I start to cry.

“They’re going to kill me,” is all I can think of. My first instinct is to crawl up into a ball and pretend that this isn’t happening, and then anger clears my brain. I’m still alive. I know they’re there. Let’s move! By the front door of the kitchen hung the coats. I grab one and put on some boots, then run into the living room where I take Dad’s old .270 Winchester off the wall. In the drawer, on the bottom of the gun case, there is a box of shells, not a full box; but I’m not taking time to count them. I glance out the front window, there are two more of them, just standing there.

George. What about George, Mom’s old dog? He must have got a bark off before they got him. Must be what woke me up and probably why they were standing there, waiting to see if he had woken anyone up… waiting to see if a light came on so they would know my room.

I had to have a plan. Maybe if I wait for them… no! I remember as a child that by opening the spare bedroom window, you could reach the kitchen roof. The kitchen was built onto the original two stories as an addition. The kitchen roof’s eaves run almost to the edge of the bedroom window. As a child, I had been able to step over to it from the windowsill—why not now?

Fear propels me up the stairs to the bedroom window, and then doubt takes over. The window—how to quietly open the window. Would it open at all? Strangely, sweat drips in my eyes.

“You have to try. It’s the only chance you’ve got,” I hear my mind say. It opens effortlessly—must be because of the cold. Now when to make my move… If they hear me, I will be dead. I didn’t have a rifle with me when I was a kid either. A crash downstairs tells me to move; they are coming in. I look down; one of them is below me.

He breaks the living room window and climbs in. I climb out. About a foot of snow covers the roof, hopefully muffling my footsteps. I am on the run now, crossing the kitchen roof, then leaping into the snow below. The snow is deep, and I flounder desperately, scrambling my way toward the tree line, which is not that far, yet an eternity away. I stiffen my back as if this would fend off the bullets about to hit my back at any second, then plunge headfirst into the underbrush.

I made it! For the first time in the last few minutes, I knew I had a chance. This newfound energy drives me down through the trees, into the valley below.

The old farmhouse was built on the edge of a deep wooded valley about half a mile wide. The valley bottom was fertile farmland with a small river meandering through the middle of it. My idea now was to keep moving until I reached the other side. There were no roads over there, and I would be able to see anyone following me. Fear propelled me, but my mind wouldn’t focus.

Why? We’d been sent back to Canada without any passports. How could we be of any danger to anyone? Yet I had this nagging fear that someone might come looking for us.

“Guess that’s what kept me alive so far,” I think as I reach the thin row of trees along the river’s edge. For the first time, I look back to see if anyone’s behind me. There’s no one in sight. I try to listen over my heavy breathing but can hear nothing. Quickly I crossed the ice on the river. Not until reaching the other side of the open flat would I feel secure enough to rest before ascending the far hill.

Other thoughts race through my mind. “What about the others? Bill and Hania, Dale and Pearl—had they already killed them, or was I the first?” I must try to warn them.

The hill is steep, but finally, I clear the trees at the top and come out onto open farmland, which stretches for miles on this side of the valley. For anyone who’s never been in the north, it’s hard to imagine how the moon lights up the terrain like a city under streetlights, creating shadows at the least indentation. Unlike the city, there are no people—only yourself and, except for the occasional wild animal, the unending world of snow and trees. It’s eerie, so quiet you can hear your heartbeat, so cold you can see your own breath. Not only are you being hunted by humans, you know that nature can kill you too.

Along the top of the valley at its crest are huge mounds of snow, not unlike sand dunes. These sand like dunes were created by the wind blowing the snow off the flatlands and piling up against the trees that bordered the valley, creating hills of snow twelve feet high in places. This snow was packed hard, and it was one of these that I ascended to survey the valley below. There they were, crossing the first flat between the far hill and the river. I had done better than I thought; although they had found my trail, it had taken a while. The moon washed the valley with light, making them vulnerable, but I guess they have no idea I am armed.

My problem is that I hate guns. Although my father was a crack shot and an excellent hunter, he had never encouraged me to use a rifle. However, he had shown me how to use one, which is right now coming in handy. Pulling the box of shells from my coat pocket, I inserted three shells into the rifle, thinking I should conserve my ammunition. Then I lay in the snow, focusing on the black objects with the scope, which turn them into humans obviously laboring in the deep snow. Remembering what I had read about when shooting downhill, one intended to shoot high. I aim at one of the figures legs, not breathing, and pull the trigger. My first sensation was that my shoulder hurt. The black object in the scope seemed to leap, and snow flew; as the sound of my rifle broke the silence.

“Roll, they’ll see the flash from my rifle. Get away from it.”

I lay face down in the snow, expecting a barrage of gunfire; although there is noise from below, nothing is being disturbed anywhere around me. I peer over the edge. Uzis. I can see the wink of gunfire in all directions; it almost makes me giddy. Hell, they have small close-range machine guns, Uzis or whatever they are called, and it’s having no effect on me whatsoever.

As my senses clear, I can see one of them thrashing in the snow. The two others are running for the tree line along the opposite side of the valley. To the west, there is a graveled road with a bridge to cross the river. Although there are no roads running toward me, this road did run north to a small village about four miles away. Just below the farmhouse, the lights of a vehicle come on and start to descend the hill toward the bridge. In my estimation, this is where the killers had left their vehicle out of sight and gone the rest of the way to the house by foot.

My thoughts went back to George.

“Should have put him away,” Mom had said. “But Dad would have never stood for it, so I guess we’ll let him die in his own time.”

I was pretty sure that George had saved my life.

In cold fury, I turn the rifle on the descending car lights and fire, ejecting the spent casing, then aim again. The sharp crack is still in my ears as I watch the lights turn slowly to the right and then fall down the steep embankment along the side of the road. The lights bury themselves in the deep snow at the bottom, leaving only the taillights sticking straight up like beacons. I feel a deep hatred inside me; I feel like shooting some more. I have turned from a man who couldn’t kill his own injured dog to a man who wants to kill anyone around him… These thoughts and the cold air bring me back to what was going on below.

The two men in the flat had now reached the trees, and the third was crawling through the snow ever so slowly in the same direction.

To my right, a figure is moving beside the ditched vehicle, and then another one appears. I guess they had dug themselves out. I loaded another cartridge into the rifle. The figures began scampering up the side of the ditch. I fire and through the scope, I watch them dive back toward the vehicle.

Actually, I couldn’t believe how well I’d done. I had hit one of them with the first shot and caused their car to run off the road with one of my others. Not bad for a guy who had not fired a gun for a while—probably just damn lucky.

Now reality begins to set in. It must be at least thirty degrees below zero. The sweat I had worked up has now turned to ice. Maybe this is what they call shock. I don’t know, but I’m starting to feel very cold. These guys are not going anywhere for a while, so what do I do? I have no mitts, no hat… better start to walk, but where? To the east, there’s a farmhouse about one and a half miles away. It’s only used in the summer months by the people who farm the land. Probably some kind of heat, still a mile and a half through three-foot deep snow, in my condition, can I make it? The lights are on in Mom’s house. It looks so safe, beckoning.

Down below in the flat, the two shadows run out and grab their downed partner. I could fire at them, but I’m too tired emotionally and physically. They’re going to end up in that house, and it seems so unfair. Determination sets in, and I sling the rifle over my shoulder. If I stay along the very edge of the valley, maybe the snow will be hard enough on top of the dunes to carry me.

I begin to walk. A mile and a half… well, I sure hope there’s some way to heat that shack if I can ever get to it. My mind begins to wander back to a time of turmoil in my life, but I had never, never thought it would lead to this.

“Just an ordinary guy,” I think. The going is good, and I begin to run a bit. I’m coming for you, July. I’ve dragged you through pure hell, but we’ll make it. I strode on with new resolve.