Carrier (1999) (50 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

As the battle group withdraws, Aegis ships and one CAP section provide a “rear guard” until the force exits the threat area. A few days later, the evacuees safely disembark; and weapons, fuel, and supplies are replenished. Then the battle group moves on to its next destination, the cycles of normal operations are reestablished, and the crews begin to think about their next port call and the exercises that will follow. While this scenario is much simplified, it illustrates how CVBGs can rapidly adapt to a fast-breaking situation. Getting a battle group into such a high state of readiness is, of course, no simple matter. The next chapter explains how Admiral Mullen, Captain Rutheford, and CAG Stufflebeem spent the hot summer of 1997 preparing their people, ships, and aircraft for the challenge of an actual deployment. Join me, and I’ll show you how they spent their vacation!

Final Examination: JTFEX 97-3

“This is 4.5 acres of sovereign U.S. territory”

George

Washington

Battle Group

In the fall of 1997 trouble was once again brewing in the Persian Gulf. Once again, Iraq was defying the authority of the United Nations Security Council, trying to hide from the world the weapons of mass destruction Saddam Hussein had spent so much to produce. As usual, the Iraqi dictator railed against UN weapons inspectors’ attempts to detect his research and production centers for chemical, biological, and nuclear arms. And once again, the world went to the brink of war.

As in previous years, this crisis required a U.S. response that was both rapid and clear. Quickly, units of the Army’s XVIII Airborne Corps were put on alert; and the U.S. Air Force dispatched reinforcements to the aerial task force (based at Prince Sultan Airbase in Saudi Arabia) already enforcing the southern Iraqi “no-fly” zone. But this time there was a complication. For the first time since August of 1990, our Persian Gulf allies denied us the use of bases on their territory. Though we still do not know whether this action resulted from pent-up frustration over our failure to form a clear policy toward Iraq, or from fear of the reaction of their own Islamic fundamentalist factions, this much was clear. If America were to react to this crisis, then the response would have to come from U.S. ships sailing in international waters.

To this end, the newly installed Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Henry Shelton, sent the word down the chain of command: “Send in the carriers.” Within days, the carrier battle groups (CVBGs) based around the aircraft carriers

Nimitz

(CVN-68) and

George Washington

(CVN-73) were sailing for the Persian Gulf, where they could quickly mount air and cruise-missile strikes against Iraqi targets should these be required. As the CVBGs rattled sabers, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan carefully constructed a diplomatic effort to persuade Saddam that further intransigence would lead to falling bombs. The persuasion—eventually—worked, and the inspectors were able to return to their jobs.

Nimitz

(CVN-68) and

George Washington

(CVN-73) were sailing for the Persian Gulf, where they could quickly mount air and cruise-missile strikes against Iraqi targets should these be required. As the CVBGs rattled sabers, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan carefully constructed a diplomatic effort to persuade Saddam that further intransigence would lead to falling bombs. The persuasion—eventually—worked, and the inspectors were able to return to their jobs.

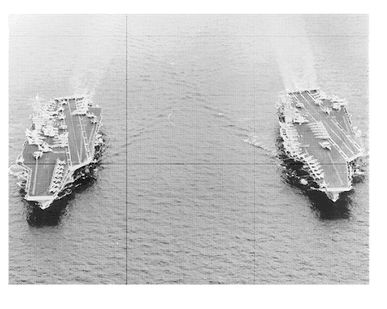

The carriers

Nimitz

(CVN-68) and

George Washington

(CVN-73) in the Persian Gulf during fall 1997. These two vessels and their battle groups comprised the bulk of the striking power that stood down Saddam Hussein during the arms inspection crisis.

Nimitz

(CVN-68) and

George Washington

(CVN-73) in the Persian Gulf during fall 1997. These two vessels and their battle groups comprised the bulk of the striking power that stood down Saddam Hussein during the arms inspection crisis.

OFFICAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO

Meanwhile, the two battle groups spent almost six months on station in the Gulf, until they were relieved of their vigil in the spring of 1998 by two more CVBGs, centered around the carriers

Independence

(CV-62) and

John

C.

Stennis

(CVN-74). The U.S. kept two carrier groups in the Persian Gulf until late May 1998, by which time tensions in the region had relaxed. Back home in America, most of us gave little thought to the thousands of men and women on these ships. Even though we may have worried a great deal about the Iraqi crisis itself, they were out there, doing a vital and dangerous job for us, and generally making it look easy. This last is a significant point: Making it look easy is hard work. It takes practice, training, intense education, constant drilling.

Independence

(CV-62) and

John

C.

Stennis

(CVN-74). The U.S. kept two carrier groups in the Persian Gulf until late May 1998, by which time tensions in the region had relaxed. Back home in America, most of us gave little thought to the thousands of men and women on these ships. Even though we may have worried a great deal about the Iraqi crisis itself, they were out there, doing a vital and dangerous job for us, and generally making it look easy. This last is a significant point: Making it look easy is hard work. It takes practice, training, intense education, constant drilling.

The process of preparing a CVBG for an overseas deployment begins months before it deploys, and it takes the efforts of every person assigned to the group, as well as thousands of others who do not leave American waters. Let’s look at part of that effort, as the

GW (George Washington)

group ratcheted up its combat skills in the summer of 1997.

Getting the Group Ready: Joint TrainingGW (George Washington)

group ratcheted up its combat skills in the summer of 1997.

You fight like you train!

Commander Randy “Duke” Cunningham, USN (Ret.)

First U.S. Air-to-Air “Ace” of the Vietnam War

First U.S. Air-to-Air “Ace” of the Vietnam War

This statement dates from the spring of 1972, soon after then-Lieutenant Cunningham and his valiant backseater, Lieutenant, J.G. “Willie” Driscoll, shot down five North Vietnamese MiG fighters and became America’s first confirmed Vietnam fighter aces. Cunningham and Driscoll’s success did not come out of the blue; their generation of naval aviators had been the first to be given a new kind of pre-combat schooling, called “force-on-force” training. Simply put, force-on-force training involves training units and personnel against role-players who simulate enemy units at the peak of their game. The first of these programs was the famous “TOPGUN” school, then located at NAS Miramar near San Diego, California. While the tools and curriculum were rudimentary by today’s standards, the results were spectacular. The Navy’s air-to-air kill ratio in Vietnam, the measure of aerial fighter performance, improved by an amazing 650%. Not surprisingly, the other services took notice.

Today, every branch of the U.S. military has multiple force-on-force training programs and facilities, and each of these has been validated by the outstanding combat performance of their graduates.

73

CVBGs, like fighter pilots, do best when they have been tuned up by means of intense force-on-force training—a tune-up that’s considerably complicated by the variety and multiplicity of roles a CVBG might be required to undertake. Today’s CVBG is more than a group of ships designed to protect the flattop. When properly deployed and utilized by the National Command Authorities (NCAs), a CVBG’s mission can range from “cooling off” a crisis to spearheading the initial phases of a major invasion or intervention.

73

CVBGs, like fighter pilots, do best when they have been tuned up by means of intense force-on-force training—a tune-up that’s considerably complicated by the variety and multiplicity of roles a CVBG might be required to undertake. Today’s CVBG is more than a group of ships designed to protect the flattop. When properly deployed and utilized by the National Command Authorities (NCAs), a CVBG’s mission can range from “cooling off” a crisis to spearheading the initial phases of a major invasion or intervention.

Meanwhile, preparing a war machine as large and complex as a CVBG for a six-month overseas cruise is a huge undertaking. In fact, the various components of the group spend twice as much time recovering from the last cruise and getting ready for the next as they actually spend out on deployment. And all of this has grown more complicated in the last decade as a result of the changes in the NCA command structure stemming from the Goldwater-Nichols Defense Reorganization Act. Back in the 1980s, and before Goldwater-Nichols, the Navy was the sole owner and trainer of carrier groups before they were sent overseas. Today, that ownership has moved to another organization, the U.S. Atlantic Command (USACOM) based in Norfolk, Virginia.

Led by Admiral Harold W. Gehman, Jr., USACOM is a mammoth organization—in fact, the most powerful military organization in the world today. USACOM essentially “owns” every Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine unit based in the continental United States. Its job is to organize, train, package, and deliver military forces for the commanders of the other unified Commanders in Chiefs (CINCs)—the heads of the various regional commands responsible for conducting military operations around the globe. Whenever the NCAs need to send an American military force somewhere in the world, the phone usually rings first in Norfolk at USACOM headquarters.

Goldwater-Nichols has also brought practical changes to the U.S. military. For instance, CVBGs now no longer operate independently of other units—or indeed of other services. So an air strike from a carrier may receive aerial tanking and fighter protection from U.S. Air Force units, and electronic warfare support from a U.S. Marine Corps EA-6B Prowler squadron, and have the target located and designated by an Army Special Forces team. This, in essence, is what is meant by “joint” warfare, and it’s far removed from Cold War practices that gave the Navy few responsibilities other than the killing of the ships, aircraft, and submarines of the former Soviet Union. Needless to say, joint war fighting skills don’t just happen. They must be taught and practiced before a crisis breaks out. The CVBG must practice not only “Naval” skills, but also “joint” skills with other services and nations.

This job falls to the joint training office (J-7) of USACOM, which lays out the training regimes for units being “packaged” for missions in what are normally known as JTFs or Joint Task Forces. Getting a particular unit ready for duty in a JTF is a three-phased program, which is supervised by individual groups of subject-matter experts. For example, on each coast a Carrier Group (CARGRU) composed of a rear admiral and a full training staff is assigned to prepare CVBGs for deployment. On the Pacific Coast, this is done by CARGRU One, while CARGRU Four does the same job for the Atlantic Fleet. The training CARGRUs supervise the various elements of the CVBGs through their three-phase workups. These break down this way:

•

Category I Training

—Service—specific/mandated training that focuses on the tactical unit level. Examples include everything from carrier qualifications to missile and ACM training at the ship/squadron/CVW level.

Category I Training

—Service—specific/mandated training that focuses on the tactical unit level. Examples include everything from carrier qualifications to missile and ACM training at the ship/squadron/CVW level.

•

Category II Training

—This is joint field training, in which the various pieces of the CVBG come together in what are known as Capabilities Exercises (CAPEXs) and Joint Task Force Exercises (JTFEXs).

Category II Training

—This is joint field training, in which the various pieces of the CVBG come together in what are known as Capabilities Exercises (CAPEXs) and Joint Task Force Exercises (JTFEXs).

•

Category III Training—

This is a purely academic training phase, which takes place just prior to the JTF deploying. Composed of a series of seminars, briefings, and computer war games, it is designed to give the unit commanders a maximum of up-to-the-minute information about the areas where they will likely be operating and the possible contingencies that they may face.

Category III Training—

This is a purely academic training phase, which takes place just prior to the JTF deploying. Composed of a series of seminars, briefings, and computer war games, it is designed to give the unit commanders a maximum of up-to-the-minute information about the areas where they will likely be operating and the possible contingencies that they may face.

These exercises provide a multi-level training regime for every member of the battle group, from the sailors in the laundries to the CVBG commander and his staff. And most participants will tell you that the pre-workup training is usually tougher than the actual overseas deployment. The old saying that sweat in training is cheaper than blood in combat remains true. In a world as uncertain as today’s, we as a nation owe the men and women of our armed forces the very toughest training we can provide for them.

74

All of this brings us down to the men and women of the

GW

group in the summer of 1997, facing a terribly real experience, designed to test the limits of their endurance and skills.

Getting the Group Ready: Part I74

All of this brings us down to the men and women of the

GW

group in the summer of 1997, facing a terribly real experience, designed to test the limits of their endurance and skills.

The countdown to

GW’s

deployment in the fall of 1997 actually began in February of 1996. That is when the battle group based around the USS

America

(CV-66) returned from their own six-month cruise to the Mediterranean Sea.

75

Since

America

had been scheduled for decommissioning and eventual scrapping, this was her final cruise. The

GW

would replace her. Other ships in this combined CVBG/Amphibious Ready Group (ARG) were scheduled for deep maintenance as soon as they arrived back home. Thus the

Wasp

(LHD-1) and the

Whidbey Island

(LSD-41) were headed into dry dock for almost a year of overhaul. Replacing them would be the amphibious ships

Guam

(LPH-9),

Ashland

(LSD-48), and

Oak Hill

(LSD-51). At the same time, a number of the escorts and submarines were swapped out, as the personnel at Atlantic Fleet Headquarters and USACOM packaged the new CVBG. Even though the CVBG would make just one cruise in this form, the plans are to reconstitute it again in a more permanent form for its 1998/ 1999 cruise.

82

GW’s

deployment in the fall of 1997 actually began in February of 1996. That is when the battle group based around the USS

America

(CV-66) returned from their own six-month cruise to the Mediterranean Sea.

75

Since

America

had been scheduled for decommissioning and eventual scrapping, this was her final cruise. The

GW

would replace her. Other ships in this combined CVBG/Amphibious Ready Group (ARG) were scheduled for deep maintenance as soon as they arrived back home. Thus the

Wasp

(LHD-1) and the

Whidbey Island

(LSD-41) were headed into dry dock for almost a year of overhaul. Replacing them would be the amphibious ships

Guam

(LPH-9),

Ashland

(LSD-48), and

Oak Hill

(LSD-51). At the same time, a number of the escorts and submarines were swapped out, as the personnel at Atlantic Fleet Headquarters and USACOM packaged the new CVBG. Even though the CVBG would make just one cruise in this form, the plans are to reconstitute it again in a more permanent form for its 1998/ 1999 cruise.

82

In February of 1996, while the thoughts of most of the group’s personnel were on their upcoming leave periods and visiting with their families and friends, at the USACOM and Atlantic/2nd Fleet headquarters planning for the CVBG’s training and deployment in 1997 had already begun. For starters, there was the scheduling of minor overhauls for the ships assigned to the CVGB that would deploy in 1997, as well as managing the usual flow of personnel coming and going to new assignments. These months of relative quiet offered a time for getting the new folks up to speed, and a chance for those remaining in the group’s units to attend technical and service schools or to take some leave.

By the fall of 1996, the various pieces of the battle group were ready to begin their Category I training. So, for example, the

Guam

ARG and the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit—Special Operations Capable (MEU (SOC)) were beginning their own workups, supervised by teams of USACOM training mentors. Meanwhile, even as CARGRU Four personnel were deep into the training of the

John F. Kennedy

(CV-67) CVBG (which would proceed the

GW

group to the Mediterranean in the spring of 1997), the CARGRU staff had already begun to assign personnel to the

GW

group to start the workup process. At the same time, the various squadrons of Carrier Air Wing One (CVW-1) began to come to life at Naval Air Stations (NASs) from Whidbey Island, Washington, to Jacksonville, Florida. About half of these squadrons would also be breaking in a new commanding officer, normally a freshly frocked commander (O-5) who had just “fleeted up” from the executive officer’s job in the unit. Along with the command changes came in-squadron training. A

lot

of it!

Guam

ARG and the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit—Special Operations Capable (MEU (SOC)) were beginning their own workups, supervised by teams of USACOM training mentors. Meanwhile, even as CARGRU Four personnel were deep into the training of the

John F. Kennedy

(CV-67) CVBG (which would proceed the

GW

group to the Mediterranean in the spring of 1997), the CARGRU staff had already begun to assign personnel to the

GW

group to start the workup process. At the same time, the various squadrons of Carrier Air Wing One (CVW-1) began to come to life at Naval Air Stations (NASs) from Whidbey Island, Washington, to Jacksonville, Florida. About half of these squadrons would also be breaking in a new commanding officer, normally a freshly frocked commander (O-5) who had just “fleeted up” from the executive officer’s job in the unit. Along with the command changes came in-squadron training. A

lot

of it!

Other books

Wild Lavender by Belinda Alexandra

Separate Kingdoms (P.S.) by Laken, Valerie

Reprisal by Colin T. Nelson

The Truth and Other Lies by Sascha Arango

Forgotten Lullaby by Rita Herron

May We Borrow Your Husband? by Graham Greene

Cigar Box Banjo by Paul Quarrington

Cartwheels in a Sari by Jayanti Tamm

Hadrian by Grace Burrowes