Carrier (1999) (57 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

The morning after the game of “Cowboys and Russians” dawned humid, overcast, and stormy. I awoke to a knock on my door from a chief petty officer at 0600 (6 A.M.). He informed me that the captain had arranged for a UH-46 VERTREP helicopter to pick up us and shuttle us over to the GW. Quickly showering and packing up my bag, I met John in the wardroom for breakfast, and we discussed our plans for returning to the carrier. Since the helicopter was due overhead at 1000 hours (10 A.M.), I took the time to go up to the bridge and thank Captain Deppe for his hospitality. Afterward, on my way down, I ran into Captain Phillips, who confirmed my own thoughts about the previous night’s proceedings. He had noted

Normandy’s

impressive performance in his report to the SOOT team leader aboard the command ship

Mount Whitney.

“Keep an eye out for things to break tomorrow,” he added slyly. Armed with this information, John and I collected our bags, and then headed aft to the helicopter hangar to await our ride back to the

GW.

Normandy’s

impressive performance in his report to the SOOT team leader aboard the command ship

Mount Whitney.

“Keep an eye out for things to break tomorrow,” he added slyly. Armed with this information, John and I collected our bags, and then headed aft to the helicopter hangar to await our ride back to the

GW.

At the hangar, a chief handed us float coats and cranial helmets, and gave us a quick safety briefing on the Sea Knight. And then at the appointed time, the UH-46 set down gently on the

Normandy’s

helicopter pad. The big twin-rotor Sea Knight was a tight fit on the small landing platform, and you could see the deck personnel carefully watching the clearance between the rotor blades and the superstructure. We quickly boarded the bird and strapped into our seats. Two minutes later, the crew buttoned up the UH-46 and lifted off into the overcast. The ride back to the GW took about fifteen minutes.

Normandy’s

helicopter pad. The big twin-rotor Sea Knight was a tight fit on the small landing platform, and you could see the deck personnel carefully watching the clearance between the rotor blades and the superstructure. We quickly boarded the bird and strapped into our seats. Two minutes later, the crew buttoned up the UH-46 and lifted off into the overcast. The ride back to the GW took about fifteen minutes.

In the ATO office, Lieutenant Navritril had good news for John. Since many of the VIPs, contractors, and other extra ship riders had flown home, he would now get to occupy a two-man stateroom up on the O-2 level near mine. He also let us know that the Challenge Athena link was working well, which meant that we could expect to see one of the opening-day NFL football games the following Sunday. “So take it easy,” he told us, “and relax the rest of the day.” Both of us gratefully took him up on this suggestion, and retired to our staterooms for a little “down” time. If things got “hot” on Monday, I wanted to be ready.

Monday, August 25th, 1997

JTFEX 97-3—Day 8: At dawn this morning, the armed forces of Korona began a general invasion of the Kartunan homeland. Elements of every branch of the Koronan military are involved, and have been identified, and are rapidly overrunning the country. The UN Security Council, the U.S. government, and the government of all coalition allies have condemned this action. Meanwhile, the UN Security Council has voted a number of resolutions, including one which encouraged “use of all necessary and appropriate force” to halt the aggression.

As soon as word of the invasion reached him, Admiral Mullen initiated a revised ROE, and put into effect the attack plans that he and his staff had been working on since we had sailed. One of his first acts was to activate Captain Deppe’s fleet air defense plan. With Deppe designated as “Alpha Whiskey” (AW—the fleet AAW commander), the three SAM ships were spread through the area to fully cover all the high-value units. The

Normandy

would stay close to the GW, while the

South Carolina

would move closer to the

Guam

ARG (the superior over-land performance of her missile radar directors gave her better inshore characteristics than those of the Aegis ships). The

Carney

would act as a “missile trap,” and work as the AAW “utility infielder” for the fleet. She would stay “up threat” of the main fleet, and do her best to break up any air attacks from Koronan air units.

Normandy

would stay close to the GW, while the

South Carolina

would move closer to the

Guam

ARG (the superior over-land performance of her missile radar directors gave her better inshore characteristics than those of the Aegis ships). The

Carney

would act as a “missile trap,” and work as the AAW “utility infielder” for the fleet. She would stay “up threat” of the main fleet, and do her best to break up any air attacks from Koronan air units.

This day would see the opening of the air campaign (which would follow the model set forth during Desert Storm). Today’s air and missile strikes were designed to eliminate the Koronan ability to hurt the coalition fleet; CVW-1 would destroy the Koronan air defense system, air force, and navy, while Tomahawk cruise-missile strikes from the

Normandy,

the

Carney,

and the submarines would decapitate the Koronan command and control network. It was a good plan. Still, the key to making a plan work is to keep it flexible enough to respond to any countermeasures that an enemy might respond with. This meant getting the TARPS F-14’s of VF-102 into the air to sweep the Gulf of Sabani, Kartuna, and Korona for targets worthy of CVW-1’s attentions. With only four TARPS-capable F-14’s, and whatever satellite imagery that could be downloaded from the Challenge Athena system, the battle group intelligence would be half-blind. Luckily, they would also have the services of the three VQ-6 ES-3’s, giving them “ears” to supplement their eyes.

Normandy,

the

Carney,

and the submarines would decapitate the Koronan command and control network. It was a good plan. Still, the key to making a plan work is to keep it flexible enough to respond to any countermeasures that an enemy might respond with. This meant getting the TARPS F-14’s of VF-102 into the air to sweep the Gulf of Sabani, Kartuna, and Korona for targets worthy of CVW-1’s attentions. With only four TARPS-capable F-14’s, and whatever satellite imagery that could be downloaded from the Challenge Athena system, the battle group intelligence would be half-blind. Luckily, they would also have the services of the three VQ-6 ES-3’s, giving them “ears” to supplement their eyes.

This day launched the entire group into wartime operating conditions; they would stay that way until the End Exercise (ENDEX) time, sometime the following week.

Tuesday, August 26th, 1997

JTFEX 97-3—Day 9: The Koronan military forces, continuing their invasion of Kartuna, claim to have taken control of more than half the country, and have flown numerous missions against the coalition air and Naval forces in the Gulf of Sabani (with results that are currently not known) . Meanwhile, the coalition forces, based around the carrier USS George Washington (CVN-73) and her battle group have begun counterattacks against the Koronan invaders.

One of the first things you get used to aboard an aircraft carrier is you never find total quiet. Down below, you hear the machinery noises that are the heart and lungs of the ship. As you rise through the decks, the noises of the flight deck begin to make themselves heard, until you reach the O-2 level, where the “airport” is on your roof. Surprisingly, you can even sleep through all the noises of the catapults firing, arresting wires straining, the tailhooks and landing gear slamming into the deck, and the jet noise coming through the armored steel deck over your head. After a while the noises blend into one another and you just sleep in spite of it all.

A young Navy maintenance technician works on an HS-11 helicopter in the hangar bay of the USS

George Washington

(CVN-73).

George Washington

(CVN-73).

JOHN D. GRESHAM

On this second day of the “war,” I wandered around the ship to get a sense of how the young men and women who were doing most of the work were handling both their work and what leisure was available to them. Down on the hangar deck, for example, I witnessed some amazing mechanical and technical exploits. Jet engines weighing five tons were changed with less than a yard’s clearance between aircraft. Kids who don’t look old enough to own a “boom box” back home handled million-dollar “black boxes.” Sweat, oil, jet fuel, hydraulic fluid, metal shavings, and salt air all mixed into a pungent smell that says only one thing: You’re in an aircraft carrier hangar bay. This is a land ruled not so much by the ship’s officers, as by those mythic people who hold the naval service together—the chiefs.

In the Navy, there is a saying that officers make decisions and the chiefs make things happen. It’s true. Here on the hangar deck, the bulk of the maintenance and repair work is done by senior enlisted personnel and non-commissioned officers (NCOs), who spend their days (and frequently nights) putting back into working order the aircraft that officers go out and break. Any machine, no matter how robust and well built, will eventually break or fail if used long enough. It therefore falls to these unsung heroes of naval aviation to do the dirty and not very well rewarded work of keeping the airplanes flying. How do the taxpayers of the United States reward these dedicated young people? While the pay of enlisted/NCO personnel has slipped a bit in the last few years (by comparison with what the average civilian earns), it is still light-years ahead of the near-poverty level of the 1970’s. In fact, the Congress has recently voted a small pay raise, and it should be in pay envelopes by the time you read this.

As for accommodations, well, as we’ve already seen, don’t expect a four-star hotel. With 90% of the crew made up of enlisted/NCO personnel, so-called “personal space” for non-officers is almost absurdly lacking. Most enlisted and NCO berthing is made up of six-man bunk/stowage units, with an attacked locker unit. Each person has an individual bunk, bunk pan, and locker. Each bunk has a reading light, privacy curtain, and fresh-air duct, all packed into a space about the size of a good-sized coffin. The six-man modules are grouped into berthing spaces, which share a communal head/shower, as well as a small open area equipped with a television, table, and chairs. Normally, when you walk through these spaces, red battle lamps (to preserve night vision) illuminate the area and allow those off their work shifts to get some sleep. In the common areas there’s usually a television going and someone is probably ironing their clothes.

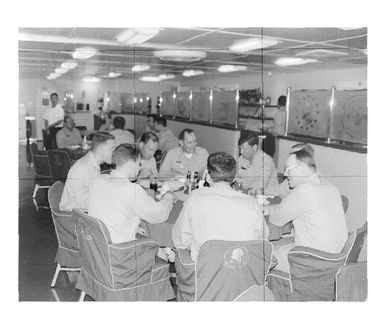

The officers’ mess in Wardroom 3 aboard USS

George Washington

(CVN-73)

George Washington

(CVN-73)

JOHN D. GRESHAM

The Navy, recognizing the necessary shortcomings of the personal accommodations, does what it can to make up for that by giving naval personnel the finest food money can buy. It’s not fancy, tending toward good, basic chow, but the mess specialists work hard to throw in favorites like pizza, stir-fry, or Mexican dishes several times a week. In addition, the dietitians try to keep food relatively low in fat by offering fresh vegetables and salads whenever possible. For the enlisted sailors, meals are usually served cafeteria-style in the large serving area forward of Wardroom 3. One of the largest open spaces in the ship, this is the central focus of the enlisted personnel aboard ship. Here they can eat, talk, attend a class, play a video game, and perhaps escape the routine for a little while. There are also other diversions.

Workout facilities are located here and there throughout the ship. These have become extremely popular in recent years, as the “hardbody” culture has become fashionable. For more serious fitness enthusiasts, there are exercise and aerobic classes held on the hangar deck several times a day, as well as a jogging group that makes the circuit of the flight deck, weather and flight operations permitting. The ship’s cable television system normally broadcasts over six channels from a small studio on the O-1 level under the island. Run by a technical team under Lieutenant Joe Navritril, it shows movies, news, ship’s bulletins, and other programming. There is also a small cable radio station, which broadcasts an “eclectic” mix of rock and roll, blues, and jazz. A four-page newspaper,

The Guardian,

comes out every day at lunch. It is a delightful mix of news from “the world,” as well as more topical pieces relating to daily life aboard the

GW.

Finally, movies (complete with bags of popcorn) and VCRs can be rented for off-duty video parties back in enlisted berthing areas.

The Guardian,

comes out every day at lunch. It is a delightful mix of news from “the world,” as well as more topical pieces relating to daily life aboard the

GW.

Finally, movies (complete with bags of popcorn) and VCRs can be rented for off-duty video parties back in enlisted berthing areas.

An innovation made possible by the Challenge Athena system is personal E-mail over the Internet for everyone on board. This is handled through the ship’s own onboard Intranet, which feeds into a central file server. Each person is assigned an E-mail account and address (aboard the GW, this ends with the suffix

@washington.navy.mil).

The messages are then routed through the server and Challenge Athena system to and from the Atlantic Fleet communications center in Norfolk, Virginia. This means that everyone on the ship with access to a computer (some are in common areas in kiosks for those who do not have personal laptops or office machines) can receive E-mail messages from home. Already, it is changing the face of shipboard life.

@washington.navy.mil).

The messages are then routed through the server and Challenge Athena system to and from the Atlantic Fleet communications center in Norfolk, Virginia. This means that everyone on the ship with access to a computer (some are in common areas in kiosks for those who do not have personal laptops or office machines) can receive E-mail messages from home. Already, it is changing the face of shipboard life.

For example, the three thousand sailors and Marines aboard the amphibious ship

Peleliu

(part of the

Nimitz

battle group, which deployed from the West Coast a month before the GW CVBG) sent over fifty thousand E-mail messages in just their first month under way! The effect on crew morale has been astounding. The arrival of Naval E-mail has come none too soon for our sailors, since the old Navy draw—“Join the Navy and See the World”—has become all but obsolete. Over the last decade, the ships of our battle groups have made less than half of the port calls on deployment that they used to make. This means that seeing foreign countries, long a recruiting attraction, has been almost eliminated. Ever since the 1979 Iran Crisis, long (ninety-plus days) line periods have become the norm for CVBGs, and this has been tough on crew morale.

Peleliu

(part of the

Nimitz

battle group, which deployed from the West Coast a month before the GW CVBG) sent over fifty thousand E-mail messages in just their first month under way! The effect on crew morale has been astounding. The arrival of Naval E-mail has come none too soon for our sailors, since the old Navy draw—“Join the Navy and See the World”—has become all but obsolete. Over the last decade, the ships of our battle groups have made less than half of the port calls on deployment that they used to make. This means that seeing foreign countries, long a recruiting attraction, has been almost eliminated. Ever since the 1979 Iran Crisis, long (ninety-plus days) line periods have become the norm for CVBGs, and this has been tough on crew morale.

Other books

Bad Miss Bennet by Jean Burnett

Divisions (Dev and Lee) by Gold, Kyell

Guardians of Magessa (The Birthright Chronicles Book 1) by Peter Last

Testimony Of Two Men by Caldwell, Taylor

Downshadow by Bie, Erik Scott de

Destroyed by Onyx (A Dance with Destiny Book 4) by JK Ensley, Jennifer Ensley

Tj and the Rockets by Hazel Hutchins

Caroselli's Accidental Heir by Michelle Celmer

The Prince of Eden by Marilyn Harris

Rabbit Creek Santa by Jacqueline Rhoades