Catherine Price (15 page)

Authors: 101 Places Not to See Before You Die

W

hen it comes to this particular type of roadside kitsch, I thought that America must be the winner. Take, for example, the giant muskie at the Fresh Water Fishing Hall of Fame & Museum in Hayward, Wisconsin. More than four stories tall and as long as a Boeing 757, the fish is the largest fiberglass sculpture in the world.

But while we might have the biggest, Australia has the most: it’s home to more than 150 giant roadside sculptures, which are affectionately known as Big Things and are becoming recognized as a type of folk art.

It all started with the Big Banana. Built in 1964 at Coffs Harbour, it’s since been joined by scores of oversize creations, from the twelve-ton Giant Koala to the Big Merino, an enormous sheep known to fans as Rambo. There’s the Big Golden Gumboot, the Big Trout, and the Big Cigar. Sometimes the sculptures are cartoonish (the Big Boxing Crocodile); sometimes they’re mundane (the Big Coffee Pot). They can even be scatological—the Big Poo appeared briefly in 2002 as a protest against sewage ocean dumping. But more commonly they celebrate food, as is the case with the Big Oyster, Big Cherries, the Big Mango, and the Big Lobster (known to locals as Larry). Some represent things you don’t really

want

to see larger-than-life: witness Big Mosquito.

Clustered mostly in the southeast, Australia’s Big Things have a campy appeal that makes it fun to take a picture next to one or two. But before you join the trend of people scheduling road trips to see all 150, be sure to evaluate your priorities: to visit

every

Big Thing, you’d have to drive the circumference of Australia.

Paulscf/Wikipedia Commons

I

f you don’t relish the idea of spending your vacation being attacked by flesh-eating insects, you should stay clear of driver ants. Native to the African rain forest, they protect themselves by plunging their giant, razor-sharp jaws into anything that stands in their way. Get pinched by one driver ant and you’ll have two irritating puncture wounds; get pinched by a colony and your African safari will come to a quick and gruesome end.

Luckily, driver ants travel in groups of up to twenty million, which makes them pretty easy to avoid. “Viewed from afar, a huge raiding column of a driver ant colony seems like a single living entity, a giant amoeba spreading across 70 meters of ground,” says Bert Hölldobler, an expert on the species. The ants also prefer the taste of insects to human flesh and, thanks to their tendency to eat anything in front of them, are excellent for pest control—provided that you’re not home at the time of their visit. If you are home and are for some reason immobilized, however, you could be eaten alive.

In the unlikely case that that happens, here are some interesting facts to distract you from the searing pain: driver ants are blind, so they communicate through pheromones. Fertile males are driven out of the colony when they’re young and spend their pubescent weeks developing into gross-looking winged insects whose bloated abdomens give them their even grosser nickname: “sausage flies.” Once a sausage fly reaches sexual maturity, he sniffs out a nearby driver ant column and then plops himself down in its path. The other ants swarm on top of him and, as if punishing a philandering husband, rip off his wings. Once he’s been suitably incapacitated, the ants carry the sausage fly off to a virgin queen, who nabs a lifetime’s worth of sperm, and then leaves him to die.

I would also not recommend seeing a column of driver ants from the perspective of a sausage fly.

I

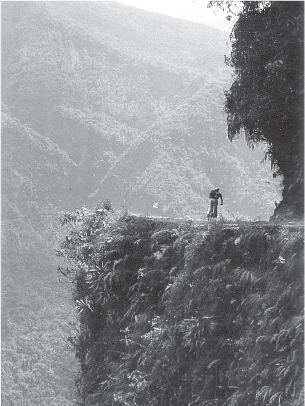

try to avoid traveling on any road that requires a prayer ceremony, which means that I’m probably never going to drive the North Yungas Road in Bolivia. Running only about forty miles from Coroico in the Amazon rain forest to La Paz, Bolivia’s capital, its unofficial nickname is El Camino de la Muerte—the Road of Death.

Its official nickname is no more reassuring: in 1995, the Inter-American Development Bank declared Yungas the World’s Most Dangerous Road. It’s been known to kill between two hundred and three hundred people a year; during one particularly bad stretch, twenty-five vehicles went over the edge in one twelve-month period—an average of about one every two weeks. The road is so dreaded that locals stop to present an offering to the goddess Pachamama—Bolivian for “Mother Earth”—before they drive it. Pachamama apparently enjoys beer; unfortunately, so do many Yungas drivers.

Look at a photograph of the road and it’s obvious why death is a concern. Despite being used for two-way traffic, there are spots where it is no more than ten feet across. The road is carved into a mountainside, which means that on one side is a rock wall; on the other is a drop of anywhere from twenty to three thousand feet. It is unpaved. There are no guardrails. In rainy season, it turns to mud; landslides frequently wipe out entire sections. It also used to be the main route between La Paz and Coroico, which means it was crowded with buses and trucks driven by men chewing coca leaves to calm their nerves. Unsurprisingly, the road is dotted with crosses and memorials to people who have lost their lives.

In an effort to improve safety, Yungas has its own rules. Descending traffic always yields to ascending. When passing, cars drive on the left side of the road instead of Bolivia’s usual right—that way, the driver on the outside will be better able to tell if his wheels are about to go over the edge. For a brief period, the road was closed to two-way traffic—a life-saving move that was reversed when truck drivers complained that they were losing too much revenue.

Here’s hoping that there’s not a truck around the corner.

Warren H/Wikipedia Commons

The biggest improvement came in 2006, when a long-awaited new road—paved and far less precipitous—opened after twenty years of construction. Most people choose it instead, but that doesn’t mean Yungas Road is empty. Truck drivers still occasionally use it, and it’s begun to attract a new group of thrill-seekers: mountain bikers. With a near-continuous descent that takes between five and six hours to ride, it’s got breathtaking (and occasionally life-taking) views—and now that there’s less traffic, it’s safer than it’s ever been. Though then again, that’s not really saying much.

ERIC SIMONS

Adventure of the Beagle

, the Musical

T

here’s a ton of stuff worth doing in Tierra del Fuego, should you find yourself there. Beautiful glaciers, for one. Also: rugged history, scenic sheep, and epic trout.

On the other side of things, there’s the

Adventure of the Beagle

, the musical. You might not be able to die a happy person without having seen Tierra del Fuego’s wildlife, but I promise, you’ll do just fine without

La Aventura del Beagle

.

Based loosely—by which I mean, essentially, not really at all—on the 1830s voyage of the young Charles Darwin and his mates through South America,

el

espactaculo del fin del mundo

—the “show at the end of the earth”—is the sort of production aimed primarily at cruise ship passengers. (Better options: Go to the onboard karaoke night! Dress up in a tux and try to learn Dutch from the captain! Jump overboard and try to swim to Antarctica!)

The

Beagle

musical takes one of the highlights of the voyage, the amazing scenery, and renders it in jagged bedsheet glaciers. It features a swarm of indigenous people played by grunting Muppets on sticks, and a group of sailors dressed in what can only be described as Parisian pastry-chef hats.

Yes, all this is bad. But what truly elevates the

Adventure of the Beagle

, the musical, into lunacy, is the singing, dancing, twenty-foot-tall fossilized giant sloth-like thing. The sloth-like thing chides Darwin in a wonderful basso profundo. It cavorts around the stage on puppet strings and appears to be made in part of NERF. It is also fluorescent green.

Naturally, the fluorescent green fossilized giant sloth-like thing is given a starring role.

We should back up a bit.

In real life, the twenty-three-year-old Charles Darwin arrived in middle Patagonia, somewhere near modern-day Bahia Blanca, in 1832. Bored out of his mind with watching the coastal sand hillocks go by (“I never knew before, what a horrid ugly object a sand hillock is,” he wrote in a letter home), and seasick from tossing about in a small boat in the fierce Patagonian wind, Darwin rejoiced at the chance to go ashore to do some fossil-hunting. One of the fossils they turned up was a giant sloth jawbone, and Darwin went on over the next few years to find several more fossilized

Megatherium

bits scattered around the Patagonian plains. If he was not the first to discover it, the fossils he sent home were at least useful in advancing

Megatherium

science, and hey, everyone loves a good giant sloth tale. Oh, and fossils—those have to do with Darwin, right?

So in the musical, the extinct sloth appears at the crucial apex of the drama, the beginning of the second act, just after the section titled “FitzRoy’s Rage” in which the narrow-minded captain bellows at Darwin for believing in fossils. (In real life, FitzRoy wrote in his own journal about his “friend” discovering the “interesting and valuable remains of extinct animals.”)

The sloth, though, makes it clear it isn’t standing for any creationist captains on

this

voyage.

“You can try to deny what your eyes meet / With some pastimes or a trip off to sea,” the sloth sings. “Go hunting, or some bingo, chess, perhaps football / Or maybe a sudden step out to the music hall. / But the more you try and try / You’ll just have to change your mind / ’Cause after all you really know / I am as real as these bones.”

And then: dancing! The sloth jerks across the back of the stage, in a kind of hip-bone-connected-to-the-leg-bone kind of way. Once finished, it toddles off and the play wears on.

Many of the great stories of history are just as great on the stage:

Les Misérables

, say, or

Monty Python’s Spamalot

. But when it comes to Tierra del Fuego and

La Aventura del Beagle

, it’s best to stick to the original source material. Or just go for the scenic sheep.

ERIC SIMONS

is the author of

Darwin Slept Here: Discovery, Adventure, and Swimming Iguanas in Charles Darwin’s South America.

S

ince Cusco is the capital city of the ancient Inca Empire and a jumping off point for Machu Picchu, you may well find yourself there before you die. But don’t forget your sunblock. As befits the former home of a sun-worshipping civilization, it has the highest levels of UV radiation in the world.

To identify the world’s worst spot, researchers examined UV data from NASA’s Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer between 1997 and 2003. They decided that despite the fact that Australia and New Zealand have the world’s highest rates of skin cancer, the highest UV levels were in the Peruvian Andes. With a UV index score of 25, Cusco came in at the top of the list.

To give you a sense of how high 25 is, consider that much like the stereo in

This Is Spinal Tap

, the scale usually only goes up to 11. The Environmental Protection Agency issues UV Alerts for anything over 6. At 11 or higher, exposed skin can burn in minutes, and the EPA and World Health Organization recommend staying inside as much as possible, which is fine for normal workdays, but not a feasible option when hiking the Inca Trail.