Catherine Price (5 page)

Authors: 101 Places Not to See Before You Die

Y

our day starts precisely at 8

A.M.

when, standing in the pitch darkness of your temporary corral, you hear the sound of people singing. “

A San Fermín pedimos, por ser nuestro patrón, nos guíe en el encierro dándonos su bendición

,” they chant, asking a guy named Saint Fermín to give them his blessing as they participate in something called an “encierro.”

“What’s an ‘encierro’?” you ask yourself, still sleepy from your long journey from your farm the day before. But before you get any answers, a gun goes off and someone presses a Taser to your skin, prodding you from complete darkness into total, blinding sunlight. Confused and frightened, you trip over your own hooves as you try to figure out what is going on. Your eyes adjust just in time to see a crowd of people, all dressed in white with silly red neckerchiefs, start to . . . hit you with rolled up newspapers? What the hell is this? And why are all the other bulls running so fast?

I’ll tell you why: because those jerks with the newspapers are now chasing you down the street, whooping and hollering and poking you with their papers. “Really?” you think, hooves skittering on cobblestones as you force yourself around a corner. “Are you

really

trying to outrun a bull?”

It’s enough to make you want to gore them, but there’s no time—you’ve now reached a large ring and are surrounded by a different group of people, who force you into a new corral and give you some food. It tastes good, but man, it’s making you sleepy. You haven’t been this tired since that breakfast they gave you the day you left the farm. Maybe you’ll just lie down for a little nap. . .

Suddenly it’s 6:30 in the evening and you’re being prodded back into that big circle, where thousands of people are staring down at you from the stands. Several men come up to you on horseback, but before you can figure out why the horses are wearing blindfolds, the men take sharp lancets and twist them into your neck and back muscles. What are they doing, trying to kill you? You try to raise your head to gore them, but the lancets are making it hard to move. You’re still really sleepy, the blood is flowing freely down your legs, a different man just came in and stuck a harpoon point in your back, and now some asshole is standing in front of you with a red cape.

www.andysimsphotography.com

This is officially the worst day ever.

Editor’s note: In addition to the Running of the Bulls/subsequent nightly bullfights that occur in Pamplona during the eight days of the Fiesta de San Fermín, watch out for the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals protest that occurs the day before the festival begins. Formerly known as the Running of the Nudes, it involves hundreds of naked people parading through the streets smeared with fake blood—and is a total buzzkill for anyone looking forward to the sight of drugged, wounded bulls being brutally slaughtered in front of a live audience.

C

ertain activities make me question how the human race survives. For example, the Cheese Rolling Competition, a yearly festival in which scores of people gather at Cooper’s Hill near Gloucester, England, for the chance to chase a piece of cheese off a cliff. Bones are broken. Joints are dislocated. Contestants are carried off the field on stretchers. This might be understandable for a sufficiently large prize, but in this particular contest, runners are risking life and limb for the glory of winning a seven-pound round of Double Gloucester cheese.

Fans of the Cheese Rolling Competition will accuse me of oversimplifying things, so let me take a step back. The proud tradition of cheese rolling dates back some two hundred years (diehard fans insist it comes from the Romans) and follows a strict order of proceedings. First, competitors line up on the top of Cooper’s Hill, a rugged, uneven pitch so steep that from the top of the slope, it appears concave. A master of ceremonies, wearing a white coat and a silly hat, escorts a guest “roller”—the person responsible for releasing the cheese—to the edge of the hill. On the count of three, the roller releases the cheese; on the fourth count, the runners throw themselves down the hill after it. Originally the point was to try to catch the cheese, but given that it can travel more than seventy miles per hour and has a one-second head start, the winner is usually just whoever crosses the finish line first.

It’s a painful race to watch. Most people lose their footing almost immediately and begin violently tumbling down the hill, bouncing onto shoulders, ankles, and heads, occasionally landing back on their feet before being thrown forward again. Lucky runners make it to the bottom intact, where volunteer rugby players known as catchers try to intercept them before they crash into the safety barrier of hay bales. Unlucky contestants are taken away by ambulance.

The 2009 competition alone saw fifty-nine injuries, of which only thirty-five were competitors. The rest were catchers and spectators, some trampled, some wounded when hit by the wayward cheese. One particularly unfortunate man held up the entire contest when he fell out of a tree.

But regardless of its inherent dangers, history dictates that the competition must continue. When World War II rationing forbade using a real round of cheese, contest organizers fashioned a cheese-shaped piece of wood with a token piece of Gloucester stowed inside. And even when the contest itself has been canceled, as it was during the foot-and-mouth scare of 2001 and again in 2003 when the contest’s volunteer Search and Rescue Assistance in Disasters teams were called off to help victims of an Algerian earthquake, organizers rolled a single piece of cheese off the hill anyway—a symbolic act to ensure that the tradition would remain unbroken. If only the same were true for contestants’ bones.

MICHAEL

AND

ISAAC POLLAN

The Worst Meal in Barcelona

I

t’d be hard to pinpoint the best meal in Barcelona, a city known for its excellent Catalonian food. But on a recent trip there, our family had no trouble identifying the worst: a frozen, microwaveable paella—basically, a Spanish TV dinner—available in low-end eateries near tourist destinations. A true paella is a delicious thing, a saffron-infused concoction of meats, vegetables, or seafood cooked with rice in a two-handled pan over an open flame until the ingredients are tender and the bottom has formed a savory crust. Unfortunately, however, the dish does not stand up well in the microwave.

We had ours one hot afternoon after leaving the Park Güell, Gaudi’s weirdly wonderful garden on a hill overlooking the city. We left the park around 4

P.M.

, famished, and could find no other place willing to serve lunch; the kitchens were closed. But not the microwaves at the place near the trinket shop. There they offered several versions of traditional foods—various tapas and raciónes and, of course, my fateful paella. I placed my order, and in the kitchen, out of sight, someone slipped it into the microwave. Several minutes later, my Spanish meal was served.

What possessed me to order it? A desire to have something indigenous, I suppose. But there was nothing indigenous about the substance on the steaming plate before me: it was a solid clump of mushy rice punctuated with dubious chunks of sausage and a few world-weary prawns.

I should have gone with the hot dog.

MICHAEL POLLAN

is the author of

The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals

and

In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto.

B

efore heading to Barcelona, my parents and I had received lists from many esteemed culinary minds as to where to spend each bite in the tapas capital of the world. But these lists did us no good when, walking back to the Metro from Park Güell, the three of us were simultaneously struck by pangs of late-afternoon hunger. I knew what this meant: far from any foodie destination, we would have to venture into a restaurant unexplored by our gourmand guides. There would be no Alice Waters in the back of our heads recommending the “ever-

so-simple” tomato breads and the Iberico ham, or Dan Barber advising us to try the fried artichokes with the lemon aioli, or even my grandmother suggesting the Pimientos de Padrón. We were truly on our own.

The restaurant we found was so bland that it didn’t even have a name. And yet this was our only choice; it was siesta, and the other shops we passed were closed. Except, of course, for this anonymous hole in the wall, which we staggered into upon spying paella on the crookedly taped menu in the front window.

As we entered we were quickly greeted and ushered to a table that was squeezed so tightly into a corner that it reminded me of a Tetris piece. I sat down and immediately noticed three ominous things: the tableware and chairs (all plastic), the fact that there was not a single Spaniard in the entire establishment, and the bathroom. Oh, the bathroom. It wasn’t politely located down the hall or in the back; no, it sat in the corner across from our table, in the dining room itself. Consisting of three small walls erected to form a box the size of a small airport bathroom stall, it leaked both smells and sounds.

But despite all of this, the actual items on the menu did not seem too nauseating. My parents, emboldened by their hunger, ordered the surf and turf paellas. I stuck to the strictly turf. After placing our order with a middle-aged and chipper man, we waited for five, ten, twenty minutes, our stomachs growling louder and louder until I was sure the entire restaurant could hear the symphony of our gastric tracts. Then, finally, the food arrived, delivered in three matching oval plastic plates with slightly elevated walls.

I stared, crestfallen at the sight of my dish. It was a large lump of brown-black gooeyness, with indecipherable chunks jutting out from the sludge. Upon the first bite, which required me to cram my plastic fork as hard as possible into the slightly crusty edges of the dish, I came to the conclusion that my paella had been frozen for a very, very long time. Perhaps the delay in service was due to the time it took our server to find an ice pick to extricate the dish from the bottom of his freezer.

But while disgusting, no one could accuse my paella of being simple. After a top note of freezer burn came the lovely astringent taste of gamy meat and mushy carrot. The rice was even more complex: clumped and congealed, certain bites were reminiscent of leather-hard slabs of clay. Others were mushy beyond recognition, saturated with a drool-like substance released from the meat that created an effect of heavily burnt oatmeal.

I’ve never seen my father so happy to pay the bill.

—

ISAAC POLLAN

I

f you’ve taken a cross-country road trip, chances are you’ve seen the signs. At its peak in the 1960s, Wall Drug—a roadside attraction in South Dakota that has become synonymous with American kitsch—was advertised on over three thousand billboards around the country.

HAVE YOU DUG WALL DRUG? FREE COFFEE AND DONUT FOR VETERANS: WALL DRUG. T-REX: WALL DRUG.

The signs were so relentless that Wall Drug became a tautology of a tourist trap: a place worth visiting only because of the billboards claiming it was worth visiting. Adding to the circularity, the advertisements themselves are now considered campy artifacts in their own right, and have sprung up in places as far away from South Dakota as Moscow, the Taj Mahal, Afghanistan, and even the South Pole.

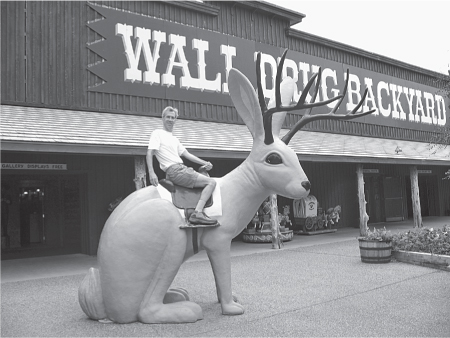

These days the actual Wall Drug advertises itself as a “76,000 square foot wonderland of free attractions” including both a life-size tyrannosaurus rex head and the world’s second-largest fiberglass jackalope. But it wasn’t always this glamorous: when the original Wall Drug opened in 1931, Wall was a tiny prairie town with fewer than four hundred residents. Wall Drug’s founders, Ted Hustead and his wife, Dorothy, liked the town because it had a drugstore for sale and a Catholic church. Their families, however, were not as easily convinced, and insisted on having a prayer circle to see if it was really a good idea. Luckily for lovers of American roadside attractions, God approved.

It takes a while, though, to go from a small family-run pharmacy to an internationally known destination, and for a while, business was slow—really slow. So slow that even five years after they’d opened—Dorothy and Ted’s self-imposed deadline to turn things around—it still was virtually nonexistent. And then one hot summer day Dorothy, watching passing carloads of sweaty travelers, stumbled upon a gimmick that, in retrospect, was genius: Wall Drug should give away free ice water.

Dorothy even came up with a slogan: “Get a soda . . . Get a root beer . . . Turn next corner . . . Just as near . . . To Highway 16 & 14 . . . Free Ice Water . . . Wall Drug.” Skeptical but supportive, Ted got a kid to help him paint the slogan on a bunch of wooden signs, then spent a weekend nailing them up on the side of the road, spaced out so that travelers could read them sequentially as they drove. According to legend, by the time he got back to the store, people were already lining up for ice water.

Julie Mangin

That Wall Drug still exists is a testament to how few manmade tourist attractions there are in South Dakota (cf., Mount Rushmore, p. 92). But it’s also a testament to clever advertising and ice cubes. Seventy-something years since Ted and Dorothy opened their shop, Wall Drug now is a sprawling cowboy-themed mall with restaurants, gift shops, a chapel, an art museum, and attractions that include a

piano-playing gorilla and an eighty-foot-tall apatosaurus. You can buy boot spurs or a “freedom pistol,” watch some singing cowboy dolls, or take a photo of your kids on the jackalope. Wall Drug still offers free ice water and 5-cent cups of coffee, but that’s about all that is recognizable from the original tiny store. It’s grown so large that it is no longer simply an attraction—Wall Drug has swallowed the town.