Challenging Depression & Despair: A Medication-Free, Self-Help Programme That Will Change Your Life (20 page)

Authors: Angela Patmore

Tags: #Self-Help, #General

‘BRAINSTORMING’

Brainstorming can offer you a fresh style of problem-solving by accessing parts of your brain that you may not normally use for this purpose. First, warm up using the following game. It may take a while, but we need to demonstrate to your satisfaction one of your brain’s many under-used skills. Take a road map or an atlas or an A to Z.

Don’t open it yet.

Write down from memory:

•

a dozen places ending in -

mouth

•

a dozen places ending in -

borough

•

a dozen places containing -

ness

(this

is

hard).

Really try to remember

without

cheating, and when you run out of options, leave it for a while and go and do something else. At first you may keep worrying away at the problem, trying hard to recall the missing place names and failing. Stop. Just leave it. Make a cup of tea, or water the garden or something. Then, as you do these

other

tasks, a mysterious thing will generally happen. Odd place names will start to pop into your head. Jot them down when they come unbidden. Then, when you have a few, go and look for them in the map index. One or two may not actually exist, or they may be slightly inaccurate versions of real place names. But some of them will be exactly right – place names that you have seen on your travels but that you didn’t know you knew, and that you certainly didn’t remember on the first ‘trawl’. What’s happening is that your brain is presenting you with raw data. It is in its unedited form, like uncut diamonds. It is up to you to make use of this data by verifying or adapting it to suit your purposes. This is how ‘brainstorming’ works.

Now brainstorm a real problem

While the place-name exercise is still fresh in your mind, brainstorm one of the problems on your grids. Write down any solutions that occur to you, even inchoate and apparently absurd ones. Weird as they may first appear, perhaps they make ‘imaginative’ sense rather than logical sense, and perhaps therefore you can use them.

Once you have mastered the grids and the brainstorming, we can move on to the more exciting business of ‘Facing the Monster’.

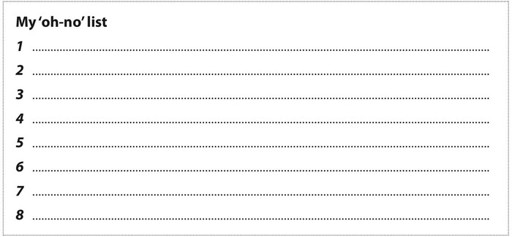

‘OH-NO’ TASKS

Choosing to tackle something you normally like to put off will demonstrate the before-and-after effects of ‘Facing the Monster’ – a principle that was the key to success for so many of my trainees. Finally tackling an onerous chore generally demonstrates two things: one, it wasn’t as bad as your vivid imagination suggested, and two, it gives you a real buzz when you finish. These ‘oh-no’ tasks may not necessarily be that important in themselves, but they are important if they have been avoided and therefore have assumed an aura of ‘cannot do’.

Examples of ‘oh-no’ tasks:

•

Clearing a cupboard

•

Organising your papers

•

Going to see a dentist

•

Sorting out finances

•

Seeing the bank manager

•

Having an eye-test

•

Breaking bad news

•

Doing self-assessment tax returns

•

Asking for a pay rise or time off

•

Sorting out a mess

•

Asking for somebody’s help

•

Turning somebody down

•

Expressing your true feelings

There are plenty more: life is peppered with them. If only we never had to do any of these, we’d all be awfully jolly all the time. But then we would not make remarkable discoveries about our abilities either. Now I want you to make your own list like this:

If you have more than eight ‘oh-no’ tasks I suggest your need for this exercise is

very great

and that you should therefore do it with alacrity. Now choose one task that you have been putting off for a

long

time. Why haven’t you done it yet? Look at it. You can tackle that. You really

want

to tackle it because continually putting it off makes you feel sick inside. It also makes you feel like a wimp. You are

not

a wimp, and you are not going to act like a wimp. So now take the following action. Yes, you may be nervous. Do it anyway.

1 Write down what you feel before you tackle the task (apprehensive, angry, frustrated, annoyed, nervous, scared, etc.).

2 Pay particular attention to

the moment you decide to go ahead.

3 Notice how you may get ‘a rush of blood’ as your brain takes command and sets to work on it.

After

you have tackled the task, sit down and consider what you feel

now

. I can assure you from my training work, my research and my own personal experience that a warm glow of satisfaction is virtually guaranteed. You won’t just have got one particularly odious job out of the way – it is more than that. You will be inwardly rewarded. You will feel positive, concentrated, constructive and creative, because you have given your brain the chance to do what it loves best and what it was designed for –

helping you to survive.

The brain is a servo-mechanism. It waits for your instructions. When these are received the effect is often palpable. You feel a thrill, a lift. And, in exactly the same way, you can summon your brain to help you with

all

your problems. It is there like a genie in a bottle, just waiting for you to ask.

Go ahead – face the monster!

WHAT PANEL MEMBERS THOUGHT

Katey

‘I have a hell of a lot of “oh-no” tasks because I find that taking antidepressants and tranquillisers can make you a bit of a Mexican – you know: “

Manyana, manyana

– I’ll do it tomorrow” … The brainstorming with the map book was freaky. On the automatic remembering I got “Knarlsborough” and “Crowborough” that I’d never even

heard

of, and I also got “

Desperough

”. I thought I must definitely have made that one up, but then when I looked there really is a Desborough. Your brain knows more than you think. The problem I wanted to face was about our drop-in closing down as that really causes problems for me. For that one I put: “Radio Essex”. No reason. But then I picked up the phone and rang their helpline. I got my views

across and people heard it. How weird is that. It gives you a boost to do stuff you don’t do.’

Barbara

‘This whole “face the monster” idea is something I will carry with me. I face each wave now head-on. You’ve got to – it’s no good running away as that doesn’t solve anything. I’ve tackled a particular problem in that I’d lost a lot of friends after my divorce and I haven’t had much of a social life. So my challenge was to get myself on two evening classes: I’m learning French and I’m doing fashion sewing and meeting some nice people. I wouldn’t have done that if it hadn’t been for the head-on challenge.’

Terry

‘When you said I had to do this I thought: you have

got

to be joking. My no-can-do was to call my ex about selling our house because of the mortgage arrears. She’s with somebody else now and we’re talking legal and **** knows what and I was bricking it. Every time I thought of doing it I would find some reason [not to], making out I’d do it this evening, or do it when I was down the pub. Anyway this went

on

and

on

. I worked out choice remarks etc., but I still wasn’t doing it. The exercises with the grids and the maps annoyed me to be honest – I thought – What the **** is this all about? I’ve got a Satnav anyway. But OK I made the call. Job done. I never made the tasty remarks, just talked normally. Bit of an anti-climax really. She was cool with it. I never even had a drink! When you actually get on and do it, you wonder what all the fuss was about. I knew that myself in fact, but if I’m totally honest I’ve been ducking things, socially and otherwise. There are calls I won’t make and buff envelopes I won’t open. I’m not saying I’m a hero now or anything but I reckon if I can do that, I can do other things.’

Talking to a stranger or making a cold call to discuss a work project

are the sorts of social challenge that many people, especially depressed people, believe they ‘cannot do’. Except that of course they can. These are some of the most popular excuses people use to prevent themselves from doing social challenges:

•

I’m nervous.

•

I’m not confident.

•

I might say the wrong thing.

•

I’m no good with people.

•

I wouldn’t know where to start.

•

They may not like me.

•

I could make an idiot of myself.

NERVOUSNESS

So you get nervous. So what? In an earlier chapter we looked at the fight-or-flight mechanism and why it should be exploited rather than feared. In unfamiliar situations ‘nerves’ are normal. Apprehension is normal. You are in a higher gear, that’s all, and it feels a bit different. Go with it – be exhilarated. Get ‘hot under the collar’ now and then. Don’t let perfectly normal reactions prevent you from doing what you want to do. And for goodness’ sake don’t let ‘stress management’ cast a pall of gloom over your life and your emotions, or you really

could

die – of boredom.

Because nervousness is normal, it happens to everybody. Most of us try to conceal it. I’ve met famous actors and sportsmen who were privately flustered, even terrified, by certain situations, but who because of their jobs had concealment down to a fine art. They

appeared

supremely confident. Some actually overcompensated, so anyone who didn’t know them thought they must be conceited.

Of course you don’t

have

to conceal your nervousness at all. Simply saying ‘I’m very nervous’ will disarm most people. They will usually give you the benefit of the doubt as we all know what it’s like to have butterflies holding a regatta in our stomachs. Among humans, it’s a given. If you perspire a lot, wash well, use antibacterial wipes and a good deodorant. If you need to go to the loo, say so. Nobody will think any less of you, unless they themselves have a social handicap that makes them judge other people for peculiar reasons.

You

are in the majority here. Nervous behaviour is what we do when situations matter to us. Who can wonder at that?

BEING ‘SHY’

If you are socially inexperienced, of course you are likely to be shy and nervous when you first make contact with other people. Most of us find walking into a roomful of strangers challenging. We do it, though, because we are naturally prone to kinship and would like to find friends and loved ones that we can confide in. So most of us just steel ourselves, walk bravely into the room and start talking – codswallop, probably, until we get into our stride. We become less nervous the more we engage with others, because if you repeatedly face the same situation your level of arousal goes down naturally – without the need for tranquillisers.

Chat rooms