Changeling

Authors: Philippa Gregory

Also by Philippa Gregory

The Tudor Court Novels

The Constant Princess

The Other Boleyn Girl

The Boleyn Inheritance

The Queen’s Fool

The Virgin’s Lover

The Other Queen

The Cousin’s War Series

Lady of the Rivers

The White Queen

The Red Queen

The Kingmaker’s Daughter

The Wideacre Trilogy

Wideacre

The Favoured Child

Meridon

Historical Novels

The Wise Woman

Fallen Skies

A Respectable Trade

Earthly Joys

Virgin Earth

Modern Novels

Alice Hartley’s Happiness

Perfectly Correct

The Little House

Zelda’s Cut

Short Stories

Bread and Chocolate

Non-Fiction

The Women of the Cousins’ War

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

A CBS COMPANY

Text copyright © 2012 by Philippa Gregory

Map of Mediterranean Sea used on endpapers from world map by Camaldolese monk Fra Mauro, 1449. Detail © DEA / F. FERRUZZI / Getty Images

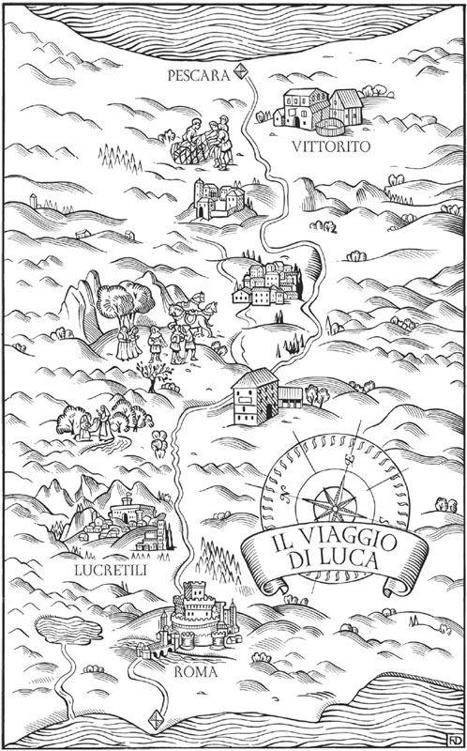

Journey map, abbey plan and chapterhead illustrations © Fred van Deelen, 2012

Section break artwork © Sally Taylor, 2012

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Philippa Gregory to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Gray’s Inn Road

London

WC1X 8HB

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

A CIP catalogue copy for this book is available from the British Library.

HB ISBN: 978-0-85707-730-1

TPB ISBN: 978-0-85707-731-8

E-BOOK ISBN: 978-0-85707-733-2

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either a product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual people, living or dead, events or locales, is entirely coincidental.

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

CASTLE SANT’ ANGELO, ROME, JUNE 1453

THE CASTLE OF LUCRETILI, JUNE 1453

THE ABBEY OF LUCRETILI, OCTOBER 1453

VITTORITO, ITALY, OCTOBER 1453

The hammering on the door shot him into wakefulness like a handgun going off in his face. The young man scrambled for the dagger under his pillow, stumbling to his bare feet on the icy floor of the stone cell. He had been dreaming of his parents, of his old home, and he gritted his teeth against the usual wrench of longing for everything he had lost: the farmhouse, his mother, the old life.

The thunderous banging sounded again, and he held the dagger behind his back as he unbolted the door and cautiously opened it a crack. A dark-hooded figure stood outside, flanked by two heavy-set men, each carrying a burning torch. One of them raised his torch so the light fell on the slight dark-haired youth, naked to the waist, wearing only breeches, his hazel eyes blinking under a fringe of dark hair. He was about seventeen, with a face as sweet as a boy, but with the body of a young man forged by hard work.

‘Luca Vero?’

‘Yes.’

‘You are to come with me.’

They saw him hesitate. ‘Don’t be a fool. There are three of us and only one of you and the dagger you’re hiding behind your back won’t stop us.’

‘It’s an order,’ the other man said roughly. ‘Not a request. And you are sworn to obedience.’

Luca had sworn obedience to his monastery, not to these strangers, but he had been expelled from there and now it seemed he must obey anyone who shouted a command. He turned to the bed, sat to pull on his boots, slipping the dagger into a scabbard hidden inside the soft leather, pulled on a linen shirt, and then threw his ragged woollen cape around his shoulders.

‘Who are you?’ he asked, coming unwillingly to the door.

The man made no answer, but simply turned and led the way, as the two guards waited in the corridor for Luca to come out of his cell and follow.

‘Where are you taking me?’

The two guards fell in behind him without answering. Luca wanted to ask if he was under arrest, if he was being marched to a summary execution, but he did not dare. He was fearful of the very question, he acknowledged to himself that he was terrified of the answer. He could feel himself sweating with fear under his woollen cape, though the air was icy and the stone walls were cold and damp.

He knew that he was in the most serious trouble of his young life. Only yesterday four dark-hooded men had taken him from his monastery and brought him here, to this prison, without a word of explanation. He did not know where he was, or who was holding him. He did not know what charge he might face. He did not know what the punishment might be. He did not know if he was going to be beaten, tortured or killed.

‘I insist on seeing a priest, I wish to confess . . .’ he said.

They paid no attention to him at all, but pressed him on, down the narrow stone-flagged gallery. It was silent, with the closed doors of cells on either side. He could not tell if it was a prison or a monastery, it was so cold and quiet. It was just after midnight and the place was in darkness and utterly still. Luca’s guides made no noise as they walked along the gallery, down the stone steps, through a great hall, and then down a little spiral staircase, into a darkness that grew more and more black as the air grew more and more cold.

‘I demand to know where you are taking me,’ Luca insisted, but his voice shook with fear.

No-one answered him; but the guard behind him closed up a little.

At the bottom of the steps, Luca could just see a small arched doorway and a heavy wooden door. The leading man opened it with a key from his pocket and gestured that Luca should go through. When he hesitated, the guard behind him simply moved closer until the menacing bulk of his body pressed Luca onwards.

‘I insist . . .’ Luca breathed.

A hard shove thrust him through the doorway and he gasped as he found himself flung to the very edge of a high narrow quay, a boat rocking in the river a long way below, the far bank a dark blur in the distance. Luca flinched back from the brink. He had a sudden dizzying sense that they would be as willing to throw him over, onto the rocks below, as to take him down the steep stairs to the boat.

The first man went light-footed down the wet steps, stepped into the boat and said one word to the boatman who stood in the stern, holding the vessel against the current with the deft movements of a single oar. Then he looked back up to the handsome white-faced young man.

‘Come,’ he ordered.

Luca could do nothing else. He followed the man down the greasy steps, clambered into the boat and seated himself in the prow. The boatman did not wait for the guards but turned his craft into the middle of the river and let the current sweep them around the city wall. Luca glanced down into the dark water. If he were to fling himself over the side of the boat he would be swept downstream – he might be able to swim with the current and make it to the other side and get away. But the water was flowing so fast he thought he was more likely to drown, if they did not come after him in the boat and knock him senseless with the oar.

‘My lord,’ he said, trying for dignity. ‘May I ask you now where we are going?’

‘You’ll know soon enough,’ came the terse reply. The river ran like a wide moat around the tall walls of the city of Rome. The boatman kept the little craft close to the lee of the walls, hidden from the sentries above, then Luca saw ahead of them the looming shape of a stone bridge and, just before it, a grille set in an arched stone doorway of the wall. As the boat nosed inwards, the grille slipped noiselessly up and, with one practised push of the oar, they shot inside, into a torch-lit cellar.