Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (24 page)

Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

7.19Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Seven

“SANDWICHES AT THE GATES”

If the UN’s Cambodia mission had put a dent in Vieira de Mello’s hopes for a “new world order,” his time in Bosnia would temporarily extinguish them. On October 7, 1993, unaware of just how dark a pall Somalia would cast over UN operations around the world, he said good-bye to his wife and sons, fifteen and thirteen, and made his way to the familiar Geneva airport to embark upon yet another journey into the unknown.

Although UN Headquarters in New York had kept him waiting for months before offering him the Bosnia posting, his bosses now wanted him in place immediately. Amid the craze of his departure, Annick Roulet, his friend and former press officer in Cambodia, had been unable to steal time to discuss how she might support him from Geneva. They had agreed to meet at the airport for a cup of coffee before his flight.

Roulet was on time, but he burst through the doors of the airport just forty-five minutes before his plane was to depart. “I’m sorry, Annick,” he said, breathlessly. “I think we’ll only manage a quick hello.” She proceeded to the nearest ticket desk and purchased a business-class ticket to London. “What have you done?” he asked when she rejoined him in the security line. “Working for you,” she said, “one learns to innovate.” He glanced at the ticket she was holding. “Why London?” he asked. “Why not London?” she answered. After clearing security, the two shared a relaxed cup of coffee in the business-class lounge in the departures area. When it was time for him to board, Roulet walked him to his gate and then retraced her steps, exiting the terminal and apologetically informing the Swissair agent that her boss had just called canceling her London meeting. She received a full refund.

Vieira de Mello knew the basics of the crisis. Slovenia and Croatia had seceded from Serb-dominated Yugoslavia in 1991, and a bloody war had ensued. At just the time he had been complaining about the slow deployment of UN peacekeepers to Cambodia in 1992, the UN’s tiny Department of Peacekeeping Operations in New York had been attempting to find an additional 14,000 peacekeepers to send to Croatia to patrol a shaky cease-fire there. Then in April 1992, with the peacekeeping office stretched to its breaking point, Bosnia too had declared independence from Yugoslavia, and Serb nationalists had declared war. Bosnia’s population (43 percent Bosnian, 35 percent Serb, and 18 percent Croat) lived so intermingled that the violence instantly turned savage.

13

Serb paramilitary forces herded Bosnian and Croat men into concentration camps, burned down non-Serb villages, and besieged a number of heavily populated towns that the UN Security Council eventually declared “safe areas.”

13

Serb paramilitary forces herded Bosnian and Croat men into concentration camps, burned down non-Serb villages, and besieged a number of heavily populated towns that the UN Security Council eventually declared “safe areas.”

With the murder of European civilians captured on television, the pressure mounted on President Bush to intervene in the Balkans as he had done over Kuwait in 1991. But the circumstances in the Gulf had been very different from those in the former Yugoslavia. Saddam Hussein had invaded a neighbor and threatened U.S. oil supplies. Bosnia was home to a messy civil war that the Bush administration did not feel threatened “vital U.S. interests.”

But because the Western media covered the Bosnian conflict incessantly, the major powers could not afford to look away entirely. The United States joined European countries in funding UN humanitarian agencies that fed the war’s victims. The Security Council voted to send UN peacekeepers to the war-torn country in order to escort the aid workers who were delivering relief, and a number of European countries contributed soldiers to the dangerous mission. By the time of Vieira de Mello’s posting, the French had put more than 3,000 troops in Bosnia, the British nearly 2,300, and the Spanish over 1,200.

1

But Western governments told their soldiers with the UN to avoid risk, and the blue helmets rarely fought back against marauding militia. Each country on the Security Council framed the crisis differently: the Bush and later Clinton administrations, which refused to put boots on the ground, blamed the Serbs for their “war of aggression”; Britain and France, which had troops in harm’s way, wanted to stay neutral in the conflict and played up a “tragic civil war”; and the Russians, out of solidarity with their fellow Orthodox Christian Slavs, sided with the Serbs. These divisions among the UN’s most powerful countries would paralyze the mission Vieira de Mello was joining.

1

But Western governments told their soldiers with the UN to avoid risk, and the blue helmets rarely fought back against marauding militia. Each country on the Security Council framed the crisis differently: the Bush and later Clinton administrations, which refused to put boots on the ground, blamed the Serbs for their “war of aggression”; Britain and France, which had troops in harm’s way, wanted to stay neutral in the conflict and played up a “tragic civil war”; and the Russians, out of solidarity with their fellow Orthodox Christian Slavs, sided with the Serbs. These divisions among the UN’s most powerful countries would paralyze the mission Vieira de Mello was joining.

For all of the shortcomings of the UN mission in Cambodia, its two concrete achievements—the return of 360,000 refugees and the elections—had earned it a fairly glowing reputation outside Asia. By contrast, UNPROFOR was already seen as a “loser.” Few Bosnians read the fine print of UN mandates and inevitably saw the peacekeepers in their flak jackets, blue helmets, and armored personnel carriers as protectors. They were thus crushed to realize that most peacekeepers saw themselves as mere monitors.

Vieira de Mello spent October 7 in Zagreb, the peaceful capital of Croatia where UNPROFOR kept its headquarters, then flew to Sarajevo. One of the UN’s most significant achievements in the region had been the establishment of a humanitarian airlift into the Bosnian capital, which was encircled by Bosnian Serb gunners. The UN relied on the airport, which it controlled, to transport its peacekeepers and supplies, to fly in journalists who were essential for maintaining public support and funding for the mission, and to deliver humanitarian relief to trapped civilians.The cargo planes were flown by American, French, British, German, and Canadian pilots, who operated what they called “Maybe Airlines.”

2

2

By the time of Vieira de Mello’s arrival, the daredevil pilots had grown quite practiced at evading Serb attacks, but it meant a roller coaster of a ride. He had been warned that Serb gunfire could pierce the base of the plane and penetrate his seat from below, so he sat atop his flak jacket and braced for what he knew would be a rapid and unwieldy descent. Starting at 18,000 feet, the plane took a steep and unforgiving dive, leveled for a short stretch, and then plunged again, this time twisting to and fro in order to prevent Serb ground missile sites from locking on. At the last minute the nose of the plane jerked upward, and the wheels crashed into the runway, jolting him and the other passengers forward. After the plane had skidded to a halt, he disembarked carrying a light suitcase and a briefcase.

The journey from the airport offered him his first in-person glimpse of the Bosnian war. Sarajevo had hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics, and he was told that the identical rectangular gray concrete apartment buildings around the airport had housed the athletes.The complex was so gutted by shell and sniper fire that he assumed it had been deserted. But a closer inspection revealed flowerpots on the window ledges, laundry hanging between telephone poles outside, and children kicking soccer balls against entranceways. Plastic sheeting affixed with the UNHCR logo had replaced glass in almost all the windows. Rusted hulks of cars had been propped on their sides along the road in a largely futile effort to shield pedestrians.

Vieira de Mello’s UN driver brought him to the bunkered compound where he would work and live for the next several months. The “UN residency” was located in the former Delegates’ Club of the Yugoslav Communist Party, and it was a frequent target of Serb sniper and shell fire. He was shown a tiny office next to the briefing room, which would double as his sleeping quarters. Because he could speak with nearly all of the UNPROFOR officers in their native tongues, he quickly became a popular presence. But the soldiers teased him for his primness. The Belgian who commanded UN forces in Bosnia, Francis Briquemont, marveled at the number of times during the day that he spotted Vieira de Mello shuttling to and from the bathroom with his toothbrush and toothpaste.

3

3

Vieira de Mello and his UN colleagues kept attuned to events in Somalia. Initially, in the wake of the October 4 firefight, the Clinton administration did just what the Reagan administration had done after the attack on the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut in 1983—it pledged it would remain until the job was done. “We came to Somalia to rescue innocent people in a burning house,” President Clinton said in an address from the Oval Office, the day of Vieira de Mello’s arrival in Sarajevo. By remaining, Clinton said, “we’ve got a reasonable chance of cooling off the embers and getting other firefighters to take our place. So now we face a choice. Do we leave when the job gets tough, or when the job is well done?” Clinton announced that he was sending some 1,700 reinforcements, 104 additional armored vehicles, an aircraft carrier, and 3,600 offshore Marines.

4

4

But as Vieira de Mello adjusted to life under siege in Sarajevo, Clinton changed his mind. On October 19 the president backtracked—again as the Reagan administration had done almost exactly a decade before—announcing that U.S. forces in Somalia would “stand down.”

5

The United States would not attempt to apprehend General Aideed. Indeed, the man whom Clinton officials had so recently branded a “thug” was now described by a Clinton spokesperson as “a clan leader with a substantial constituency in Somalia.”

6

5

The United States would not attempt to apprehend General Aideed. Indeed, the man whom Clinton officials had so recently branded a “thug” was now described by a Clinton spokesperson as “a clan leader with a substantial constituency in Somalia.”

6

Vieira de Mello and his UN colleagues in Bosnia saw that the fates of the two missions were intertwined. In Somalia U.S. troops henceforth rarely ventured out of their compounds. “Force protection” became the American mantra. One U.S. officer was quoted in the

Washington Post

on the eve of his departure. “We’re not cops and we’re having to adopt war-fighting technology for a fugitive hunt in a city of about a million,” he said.

7

Washington Post

on the eve of his departure. “We’re not cops and we’re having to adopt war-fighting technology for a fugitive hunt in a city of about a million,” he said.

7

Bosnia was similar to Somalia,Vieira de Mello understood, in that non-combatants in both places were the prime victims of the violence and the prime pawns of political leaders. Once-bustling cities were held under siege by Serb gunners, and snipers fired upon civilians carrying water or UN rations. The Bosnian army, which was much weaker than its Serb opponent, often positioned its weapons in civilian neighborhoods, despite knowing that the Serbs would retaliate disproportionately. They did so in part because the front lines ran close to the center of town and also in order to camouflage the few heavy weapons they had in their possession. The UN estimated that more than 90 percent of the 100,000 people eventually killed in the conflict were civilians. These “unconventional wars” would be the wars of the future.

Vieira de Mello loved being back with the military. He settled into a routine in Sarajevo, offering his political advice to Stoltenberg in Zagreb and counseling General Briquemont in Sarajevo, while building close ties with the key

Serb and Bosnian personalities. He was told his time in Bosnia would entail negotiating prisoner exchange agreements, cease-fires, and access for UN aid convoys. Prominent Western diplomats would be the ones to try to craft a lasting political settlement.

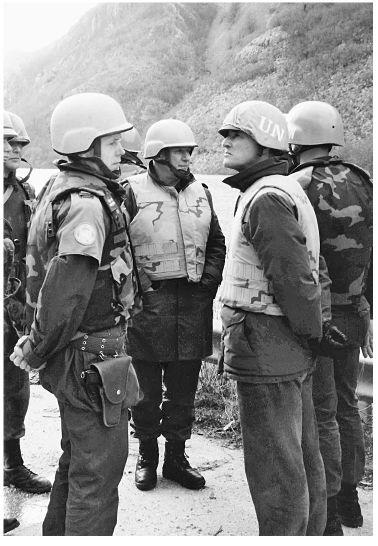

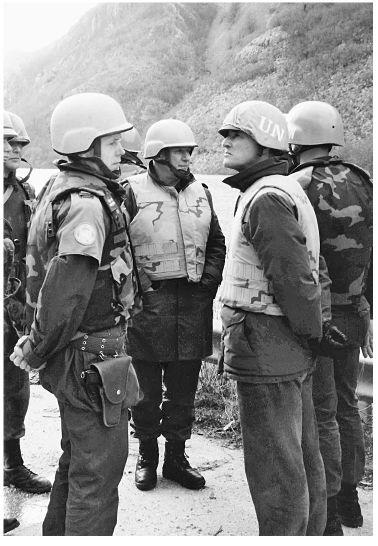

Vieira de Mello

(right)

and UN Bosnia Force Commander Francis Briquemont

(center)

scouring the Bosnian hills.

(right)

and UN Bosnia Force Commander Francis Briquemont

(center)

scouring the Bosnian hills.

Stoltenberg was a career Norwegian politician, not a UN veteran. This led him to make choices that his new aide did not like.Vieira de Mello believed that the UN drew legitimacy and strength from the geographical diversity of its field staff. He was thus aghast when Stoltenberg decided to hire one Norwegian as his adviser and another as his deputy chief of mission. “He can’t do what he’s doing,” Vieira de Mello fumed to colleagues. “He’s not establishing a Norwegian foreign ministry in exile. He’s working now for the United Nations.” Stoltenberg, for his part, valued efficiency above what he saw as the UN’s overly romantic commitment to multinationality. He also did not think that his staffing choices were unusual. “It is common to have thirty French or fifty Americans in a mission,” he says, “but when you have three Norwegians, people start to talk.” Vieira de Mello, who rarely picked losing battles, avoided raising the matter with Stoltenberg directly.

Since the Serbs frequently obstructed the movement of UN relief deliveries, he purposefully cultivated a warm relationship with Bosnian Serb political leader Radovan Karadžić, who before the war had worked as a psychiatrist in Sarajevo and fancied himself a poet. Vieira de Mello was repulsed by the Bosnian Serb leader’s anti-Muslim fervor and unimpressed by his poetry, but he was determined—just as he had been with the Khmer Rouge’s Ieng Sary—to do what it took to butter up the Bosnian Serbs’ most influential politician. On one occasion, when he visited Bosnian Serb headquarters in the town of Pale, he brought a copy of

The New York Review of Books

as a gift to Karadžić, because it featured a cover story on psychiatry.

8

Whenever the Serb leader saw fit to go on long rants about how Serbs were saving Christian civilization from a Muslim jihad, Vieira de Mello gave Karadžić his full attention. The only hint of his impatience with the Serb was the incessant jittering of his leg beneath the table. Alone with friends or colleagues, he complained about Karadžić’s bloviating and his incessant references to Serb grievances dating back to the fourteenth century. He said that he was tempted to open every meeting in the Balkans with the proviso “Today we are going to begin this meeting in 1945.” But in practice he never dared to alienate his interlocutors.

The New York Review of Books

as a gift to Karadžić, because it featured a cover story on psychiatry.

8

Whenever the Serb leader saw fit to go on long rants about how Serbs were saving Christian civilization from a Muslim jihad, Vieira de Mello gave Karadžić his full attention. The only hint of his impatience with the Serb was the incessant jittering of his leg beneath the table. Alone with friends or colleagues, he complained about Karadžić’s bloviating and his incessant references to Serb grievances dating back to the fourteenth century. He said that he was tempted to open every meeting in the Balkans with the proviso “Today we are going to begin this meeting in 1945.” But in practice he never dared to alienate his interlocutors.

Other books

Molly Moon & the Monster Music by Georgia Byng

The Bachelor Boss by Judy Baer

Wild Hearts (Blood & Judgment #1) by Eve Newton, Franca Storm

Unlucky For Some by Jill McGown

Fraudsters and Charlatans by Linda Stratmann

A Hidden Place by Robert Charles Wilson

Wolf Shadow by Madeline Baker

The Dance Off by Ally Blake

La mano izquierda de Dios by Paul Hoffman