Inside the Centre: The Life of J. Robert Oppenheimer

Read Inside the Centre: The Life of J. Robert Oppenheimer Online

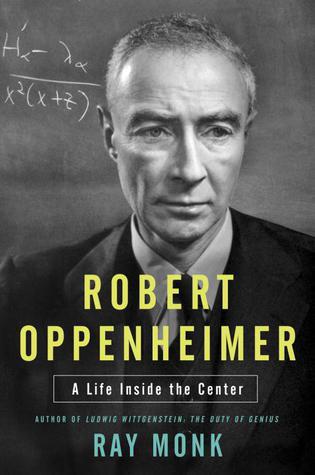

Authors: Ray Monk

Contents

1. ‘Amerika, du hast es besser’: Oppenheimer’s German Jewish Background

8. An

American

School of Theoretical Physics

14. Los Alamos 3: Heavy with Misgiving

J. Robert Oppenheimer is among the most contentious and important figures of the twentieth century. As head of the Los Alamos Laboratory, he oversaw the successful effort to beat the Nazis to develop the first atomic bomb – a breakthrough which was to have eternal ramifications for mankind, and made Oppenheimer the ‘father of the Bomb’.

Oppenheimer was a man of diverse interests and phenomenal intellectual attributes. His talent and drive allowed him, as a young scientist, to enter a community peopled by the great names of twentieth-century physics – men such as Bohr, Born, Dirac and Einstein – and to play a role in the laboratories and classrooms where the world was being changed forever.

But Oppenheimer’s was not a simple story of assimilation, scientific success and world fame. A complicated and fragile personality, the implications of the discoveries at Los Alamos were to weigh heavily upon him. Having formed suspicious connections in the 1930s, in the wake of the Allied victory in World War Two, Oppenheimer’s attempts to resist the escalation of the Cold War arms race would lead many to question his loyalties – and set him on a collision course with Senator Joseph McCarthy and his witch hunters.

As with Ray Monk’s peerless biographies of Wittgenstein and Bertrand Russell,

Inside the Centre

is a work of towering scholarship. A story of discovery, secrecy, impossible choices and unimaginable destruction, it goes deeper than any previous work in revealing the motivations and complexities of this most brilliant and divisive of men.

Ray Monk is the author of

Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius

for which he won the Mail on Sunday/John Llewellyn Rhys Prize and the Duff Cooper Award, and

Bertrand Russell: The Spirit of Solitude

. He is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Southampton.

Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius

Bertrand Russell: The Spirit of Solitude

Bertrand Russell: The Ghost of Madness

F

IRST SECTION

1

Oppenheimer with his mother (© Historical/CORBIS);

2

Oppenheimer in the arms of his father (© Historical/CORBIS);

3

Oppenheimer building with blocks (© Historical/CORBIS);

4

155 Riverside Drive (© Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations);

5

Oppenheimer at Harvard (© Harvard University Archives);

6

William Boyd (© The National Library of Medicine);

7

Frederick Bernheim (image provided by the Duke Medical Center Archives);

8

Paul Horgan (© J. R. Eyerman/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images);

9

The Upper Pecos Valley (courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives, New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe/053755);

10

Inside the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge (© Omikron/Science Photo Library);

11

Paul Dirac (© Bettmann/CORBIS);

12

Patrick Blackett (© Science Photo Library);

13

Niels Bohr (© Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory/Science Photo Library);

14

Max Born (© Bettmann/CORBIS);

15

Charlotte Riefenstahl (© Göttingen Museum of Chemistry);

16

Werner Heisenberg (© Bettmann/CORBIS);

17

Paul Ehrenfest;

18

Oppenheimer on Lake Zurich with I. I. Rabi, H. M. Mott-Smith and Wolfgang Pauli (© AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives);

19

Oppenheimer at Berkeley (courtesy of the Department of Physics, Physics and Astronomy Library);

20

Oppenheimer with Robert Serber (© New York Times/Redux/eyevine);

21

Ernest Lawrence (© AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives);

22

Kitty (© Historical/CORBIS);

23

Perro Caliente (© Peter Goodchild);

24

Haakon Chevalier (courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley);

25

Frank Oppenheimer;

26

Jean Tatlock (© Dr Hugh Tatlock);

27

Steve Nelson (© United Press International Photos);

28

Joe Weinberg, Rossi Lomanitz, David Bohm and Max Friedman;

29

The staff of the

Radiation Laboratory sitting on the 60-inch (© Science Source/Science Photo Library)

ECOND SECTION

1

Julian Schwinger (© Estate of Francis Bello/Science Photo Library);

2

Richard Feynman (© Tom Harvey);

3

The Los Alamos Ranch School (© Digital Photo Archive, Department of Energy (DOE), courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives);

4

General Groves (© Los Alamos National Laboratory/Science Photo Library);

5

Enrico Fermi (© Argonne National Laboratory/Science Photo Library);

6

The graphite pile at Stagg Field (© Historical/CORBIS);

7

Hans Bethe (© Science Source/Science Photo Library);

8

Klaus Fuchs (© Keystone/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images);

9

Edward Teller (© University of California Radiation Laboratory/Science Photo Library);

10

Seth Neddermeyer’s early attempts at implosion (courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives);

11

The Nagasaki and Hiroshima bombs (Claus Lunau/Science Photo Library);

12

The ‘Little Boy’ design, as reverse engineered by John Coster-Mullen;

13

Workers at Oak Ridge (© Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Digital Photo Archive, Department of Energy (DOE), courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives);

14

Preparing the Trinity Test (courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives);

15

Preparing the Trinity Test, landscape (courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives);

16

The Trinity explosion (© Historical/CORBIS);

17

Oppenheimer and Groves at the Trinity Test site (Emilio Segrè Visual Archives/American Institute of Physics/Science Photo Library);

18

The effects of the atomic bombs in Japan (courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives);

19

Oppenheimer and Kitty in Japan, 1960 (© Historical/CORBIS);

20

The cover of the first issue of

Physics Today

(courtesy of Berkeley Laboratory);

21

Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard (© Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

22

The Ulam-Teller design (© Carey Sublette and the NuclearWeaponArchive.org);

23

The Mike Test;

24

Oppenheimer lectures Ed Murrow (© Bettmann/CORBIS);

25

Oppenheimer with Paul Dirac and Abraham Pais at the Institute for Advanced Study (© Alfred Eisenstaedt/Getty Images);

26

Oppenheimer, Toni and Peter at Olden Manor, Princeton (© Alfred Eisenstaedt/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images);

27

Lewis Strauss (© Bettmann/CORBIS);

28

Edward Teller congratulates Oppenheimer on his Fermi Prize (© Ralph Morse/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images);

29

Oppenheimer speaking at last visit to Los Alamos (© Oppenheimer Archives/CORBIS);

30

Oppenheimer photographed for

Life

magazine (© Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

The Life of J. Robert Oppenheimer

Ray Monk

THE ORIGINS OF

this book lie in a review I wrote about fifteen years ago of a reissued edition of

Robert Oppenheimer: Letters and Recollections

, edited by Alice Kimball Smith and Charles Weiner. Until then, I knew about Oppenheimer only what everybody knows: that he was an important physicist, that he led the project to design and build the world’s first atomic bomb, and that he had his security clearance taken away from him during the McCarthy era because of suspicions that he was a communist, or even possibly a Soviet agent.

What I did not know until I read this collection of his letters was what a fascinatingly diverse man he was. I did not know that he wrote poetry and short stories, that he had a deep love and wide knowledge of French literature, that he found the Hindu scriptures so inspiring that he learned Sanskrit in order to read them in their original language. Nor did I know how complicated and fragile his personality was, nor how intense his personal relations were with his father, his mother, his girlfriends, his friends and his students.

Learning all this, I was surprised to discover that no full and complete biography of him had, at that point, been written. There was, I said in my review, a really great biography waiting to be written about Oppenheimer, a biography that would attempt to do justice both to his important role in the history and politics of the twentieth century and to the singularity of his mind, to the depth and diversity of his intellectual interests. Such a book would need to describe and explain his contributions to physics and to place them in their historical context. It would need to do the same with regard to his other intellectual interests and to his participation in public life. It would not be an easy book to write. In fact, it seemed perfectly possible that it would never be written.

Since I wrote that review, several books about Oppenheimer have been written and published, which attempt to rise to at least some of the

challenges I described. Chief among these is

American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer

by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, a book that was a long time in the making and the result of a staggering amount of research.

American Prometheus

is a very fine book indeed, a monumental piece of scholarship that I have had at my side ever since it was published. However (partly to my relief, since I was, by the time this book appeared, engaged on my own book), it is not the book I envisaged when I reviewed Smith and Weiner. Though Bird and Sherwin describe in exhaustive detail Oppenheimer’s personal life and his political activities, they either ignore altogether or summarise very briefly his contributions to physics.