Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (85 page)

Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

3.84Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Recovering Vieira de Mello’s body remained a risky task, as the rubble continued to shift. Davie and the U.S. engineer removed some electric cabling that was blocking the way. They tied a rope around his waist, and the soldiers on the top floor pulled so that he was finally yanked from the protected triangle abutting the shaft. This was the first time Davie was able to see Vieira de Mello’s body. His legs were lacerated. His left sleeve was torn and his left hand was covered in blood. Improbably, he had been lying on a part of the UN flag that had hung in his office. He was pulled up to the third floor and placed on a stretcher. It was around 9 p.m.

Ghassan Salamé was asked to identify Vieira de Mello’s body. He headed up the stairs and pulled back the sheet. Vieira de Mello looked calm. The only visible sign of trauma were small specks of blood on his bronze face. He was driven to the morgue at a U.S. base near the airport, where around fifteen bodies were already lying inside the U.S. Army tent.

At 2:24 a.m. East Timor time (9:24 p.m. Baghdad time, 2:24 p.m. Brazil time, 1:24 p.m. New York time), CNN correspondent Michael Okwu said, “We understand, Kyra, from the UN spokesman’s office, that Sergio Vieira de Mello has, in fact, passed away. We understand that this was given to us just moments ago—Mr. Vieira de Mello, of course, a fifty-five-year-old veteran, a Brazilian diplomat who was highly respected here at the United Nations.” Adrien, Laurent, and Annie Vieira de Mello saw this announcement before they heard from anybody at UN Headquarters.

Not long afterward,Wolf Blitzer turned to the camera and told his viewers that it was their turn to weigh in on the story. “Our Web question of the day is: ‘Is Iraq becoming a quagmire for the U.S.?’ We’ll have results later in this broadcast.”

In Rio de Janeiro, Vieira de Mello’s eighty-five-year-old mother, Gilda, was confused. People who lived in her apartment building, family members, and close friends had been arriving at her apartment all day. Complete strangers were even gathering outside on the street. Afraid all summer that her son would be confused for an American, she had increased her dosage of antianxiety medication. André Simões,Vieira de Mello’s nephew and godson; Antonio Carlos Machado, his closest childhood friend; and Dr. Antonio Vieira de Mello, his closest cousin, broke the news. When she let out screams, Dr. Vieira de Mello administered sedatives.

At the Canal Hotel, Larriera was still awaiting news. Around 9 p.m., fifteen minutes after the U.S. officer told her Vieira de Mello had been helicoptered to a hospital, she overheard Lopes da Silva say to somebody else, “Sergio is dead.” She began screaming and rushed toward him. “Tell me it’s not true,” Larriera pleaded. Lopes da Silva turned toward her and said, “He’s gone.”

Larriera refused to leave the Canal Hotel until she saw his body, but at 11 p.m. she was informed that it had already been transported to the American morgue. She was taken to a private home rented by UN officials and given a sedative. At the crack of dawn the next morning, she demanded to be brought to him. When her colleagues refused, she left the house and began walking in what she thought was the right direction. A UN official quickly caught up with her and drove her to her hotel, where she was told by Ronnie Stokes, the head of administration, that she and other survivors were being evacuated. Back in the room that she and Vieira de Mello had shared for more than two months, she packed up eight pieces of luggage and retrieved a suit he had had specially tailored in Thailand on their trip, as well as the green tie she had given him for his birthday.

Pichon and another of Vieira de Mello’s bodyguards, Romain Baron, who had checked himself out of an Italian hospital despite suffering a bad shrapnel wound to the shoulder, took the suit to the morgue.There they washed their boss’s body and ripped the back of the suit in half so as to be able to dress him. Baron placed a rosary in his hand.The two bodyguards then said good-bye. Vieira de Mello looked elegant to the end.

In the end Salamé helped arrange for Larriera to go to the morgue.When she arrived, she ran inside, only to find Vieira de Mello lying on the table. It was then, gazing down at the lifeless body, that his death sank in. “His body was there,” she recalls. “But Sergio was gone.” The suit suddenly looked too big on him. He was wearing his gold engagement ring, which had “Carolina” inscribed on the back, and the gold chain he had worn for many years, with a golden "C” he had taken from her necklace and worn as a pendant. The blast had somehow stripped him of his silver necklace and silver dog tags, which had borne his name, his birth date, and an engraved UN flag.

From his first day in Iraq he had kept on his nightstand an e-mail that Larriera had sent him, urging him to keep faith in himself while there. “While Iraq is a deviation from our goal of permanently establishing ourselves and our life,” she had written him, “nothing will separate us again. We are one, and we will walk on this road of life together.” On this day, their last together, she folded up the e-mail, which she had retrieved from their room at the Cedar, and placed it in his pocket. “I will always love you, Sergio,” she said, sobbing. Before she left, she was given a small U.S. Army bag with Vieira de Mello’s possessions: bloody dollar bills, Chapstick, a bloody handkerchief, and the engagement ring they had taken off his finger.

The same day, by coincidence, East Timorese officials were holding a ceremony to rebury those who had died in the war of independence against Indonesia.They had gathered more than six hundred skeletons in Waimori, a four-hour drive from Dili. Some twenty thousand mourners and dignitaries stood solemnly to pay their respects to the fallen guerrillas. Xanana Gusmão stepped up on the stage to make his remarks. He informed the audience that Sergio Vieira de Mello had been killed by a bomb in Iraq. The audience gasped. When Bishop Felipe Ximenes Belo read the long list of names of martyred Timorese, he added one more: that of Sergio Vieira de Mello.

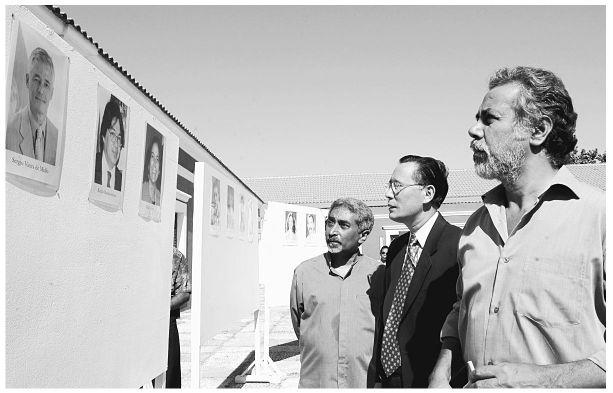

President Xanana Gusmão (right) and Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri (left) in East Timor.

Twenty-two

POSTMORTEM

The night of August 19 the UN officials who had survived the Canal Hotel bombing gathered in their Baghdad hotels. Many were so paralyzed by shock that they had not yet cried. But when they walked into the hotels where they slept and saw colleagues whose fates they had not known, the events of the day hit them and they wilted. Often it was only when they reached their rooms and looked in the mirror that they realized they were covered in blood. In many cases the blood was not their own. Information on the dead and injured was hard to come by, but surviving staff were under the impression that anybody who had been in, near, or under Vieira de Mello’s office on the third floor had not made it.

Hearsay competed with facts all night, but the list of the known dead and gravely wounded was long. Many of the deceased had been killed instantly, and their families were notified. For others, like Lyn Manuel, Vieira de Mello’s Filipina secretary, and Nadia Younes, his Egyptian chief of staff, rumors of sightings persisted well into the evening. Finally both the Manuel family in Queens and the Younes family in Cairo were notified that neither woman had survived the blast.

Those listed as killed, in addition to Sergio Vieira de Mello, the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General, were:

United Nations

Reham al-Farra, 29, Jordan, spokesperson

Emaad Ahmed Salman al-Jobory, 45, Iraq, electrician

Raid Shaker Mustafa al-Mahdawi, 32, Iraq, electrician

Leen Assad al-Qadi, 32, Iraq, information assistant

Ranillo Buenaventura, 47, Philippines, secretary

Rick Hooper, 40, United States, political officer

Reza Hosseini, 43, Iran, humanitarian affairs officer

Ihssan Taha Husain, 26, Iraq, driver

Jean-Sélim Kanaan, 33, Egypt/France, political officer

Christopher Klein-Beekman, 32, Canada, program coordinator for United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF)

Marilyn “Lyn” Manuel, 53, Philippines, secretary

Martha Teas, 47, United States, manager of the UN Humanitarian Information Center

Basim Mahmood Utaiwi, 40, Iraq, security guard

Fiona Watson, 35, United Kingdom, political affairs officer

Nadia Younes, 57, Egypt, chief of staff

Others

Saad Hermiz Abona, 45, Iraq, Canal Hotel cafeteria worker

Omar Kahtan Mohamed al-Orfali, 34, Iraq, driver/interpreter, Christian Children’s Fund

Gillian Clark, 48, Canada, child protection worker, Christian Children’s Fund

Arthur Helton, 54, United States, director of peace and conflict studies at the Council on Foreign Relations

Manuel Martín-Oar Fernández-Heredia, 56, Spain, assistant to the Spanish special ambassador to Iraq

Khidir Saleem Sahir, Iraq, driver

Alya Ahmad Sousa, 54, Iraq, consultant to the World Bank Iraq team

Secretary-General Annan was not known for allowing people to get close to him, but he spoke of Vieira de Mello and Younes as if they were exceptions. He had known Vieira de Mello since their days together in UNHCR in the 1980s, and Younes had been his chief of protocol for three years in New York. As he stopped briefly at Stockholm’s airport en route back to New York, he was less diplomatic than usual. “We had hoped that by now the Coalition forces would have secured the environment for us to be able to carry on ... economic reconstruction [and] institution building,” Annan said. “That has not happened.” Ever careful, though, he added, “Some mistakes may have been made, some wrong assumptions may have been made, but that does not excuse nor justify the kind of senseless violence that we are seeing in Iraq today.”

Annan did not consider pulling the UN out. “The least we owe them is to ensure that their deaths have not been in vain,” he said. “We will persevere.” The UN had operated in Iraq for more than twelve years without being attacked. “It’s essential work,” he said. “We are not going to be intimidated.”

1

Annan’s line echoed that of U.S. officials in Iraq and Washington.

1

Annan’s line echoed that of U.S. officials in Iraq and Washington.

Other books

Mistletoe and Mischief by Patricia Wynn

The Curse of Babylon by Richard Blake

Lords of Retribution (Lords of Avalon series) by Richards, K. R.

A Forge of Valor by Morgan Rice

The Chef by Martin Suter

Westward Dreams by Linda Bridey

How Stella Got Her Groove Back by Terry McMillan

Phantoms Can Be Murder: Charlie Parker Mystery #13 by Connie Shelton

The French War Bride by Robin Wells