Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (86 page)

Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

13.85Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

On August 21 Kevin Kennedy, the former U.S. Marine and UN problem-solver, landed back at Baghdad airport in Iraq. Although he had lost Vieira de Mello and several other close UN colleagues, he knew that he was in a more stable psychological state than those who had actually lived through the attack, who were in no condition to manage arranging the evacuation of the wounded and the deceased.

Kennedy walked across the tarmac, where some fifty shell-shocked UN personnel were gathered in advance of being evacuated to Jordan. Carolina Larriera approached him, frantic. “I’m not getting on the plane to Amman,” she said.“They are making me leave. I want to go on the plane with Sergio.” The Brazilian government had dispatched an air force 707 to Baghdad to collect his body. Kennedy had been told that Annie would be on the Brazilian plane. He called Lopes da Silva. “Carolina wants to fly with Sergio,” he said.“What the hell do we do?” Lopes da Silva was decisive. “Get her on that plane to Amman,” he said. “Get her out of here.” Kennedy assured Larriera that she would be able to meet the Brazilian plane in Amman, and she was steered onto the UN plane with the other bomb survivors.

Most of the families of the deceased had begun making burial arrangements. Lyn Manuel’s grief-stricken family in Woodhaven, Queens, was no exception. Manuel’s husband of thirty-four years and her three children had already held a private memorial service at their home and were awaiting the return of Manuel’s body for the funeral. At 3 a.m. on August 21, two days after the bombing, Eric and Vanessa, Manuel’s two youngest children, aged twenty-five and twenty-nine, were sitting in their living room telling stories about their mother. The phone rang, and Eric answered it. The line was filled with static. Eric’s heart stopped. "Hello,” the voice said. “Hello, Eric. It’s Mom.” “What?” he said. “It’s Mom,” she answered. “Eric, it’s Mom.” Seeing the look on her brother’s face, Vanessa ran upstairs and picked up the other phone. Lyn Manuel, whom UN officials in Iraq had listed among the dead on August 19, was calling from a U.S. Army clinic outside Baghdad. She had regained consciousness next to a patient with a cell phone. Manuel panicked when she heard the voice of her daughter, who lived in Hawaii and had not planned a trip to Queens. “Is everybody okay?” Manuel asked. Her son and daughter assured her that everything was fine and did not tell her about the mix-up. Instead, they wished her a happy fifty-fourth birthday and told her they loved her. After hanging up, they collapsed in sobs of joy.

As the bomb survivors prepared to fly out of Baghdad, an FBI team established a kind of checkout procedure by which UN staff left their names and contact details. Many of the UN officials questioned were hostile to the FBI, which they saw as yet another offshoot of the U.S. occupation, but most agreed to make themselves available for future questioning. The FBI inquired particularly about the UN’s Iraqi staff, and two Iraqis who worked for the UN were detained and interviewed repeatedly in the days that followed.The United Nations did little to keep survivors and family members informed of the progress of the investigation, beyond setting up a confidential Web site and a Listserv ([email protected]) through Vieira de Mello’s office in Geneva.The site was barely used.

On August 22, the day after Larriera and other survivors were shepherded out of Baghdad, the Brazilian government’s 707 arrived to collect Vieira de Mello’s casket. The plane would then make its way to Geneva, where it would collect Annie, Laurent, Adrien, and their guests, en route to Brazil. William von Zehle, the Connecticut fireman who had kept Vieira de Mello company in the shaft during his last hours, had written a letter to Annan in which he described fragments of what Vieira de Mello told him under the rubble.Von Zehle distinctly recalled the dying UN official saying, “Don’t let them pull the mission out.”

On the tarmac at the coffin ceremony, Benon Sevan, the highest-ranking UN official on the scene, quoted from von Zehle’s letter in urging a continued UN presence:

Sergio was fully committed to the United Nations until his last breath. Even under the most extreme pain, pinned down under the rubble of his office, he said ... "Don’t let them pull the mission out.” ...

Our beloved Sergio . . . Bowing before you at this very difficult hour, I assure you that no heinous act of terrorism will deter us from carrying out the noble tasks entrusted to us in the service of the United Nations.We will resume our activities as of tomorrow and continue your legacy.

2

2

Those closest to Vieira de Mello were skeptical that, having so soured on the ineffectual UN mission, he would have made such an appeal. But Annan and the press henceforth made frequent reference to his alleged last wishes. “His dying wish was that the United Nations mission there should not be pulled out,” Annan declared. “Let us respect that. Let Sergio, who has given his life in that cause, find a fitting memorial in a free and sovereign Iraq.”

3

3

The media tried to provoke Annan into blaming the Bush administration for going to war in the first place, but the secretary-general remained politic. “We all know the military action was taken in defiance of the Council’s position,” he said. “Lots of people in this building, including myself, were against the war, as you know, but I think we need to put that behind us.That is something for historians and political scientists to debate.” The UN’s focus needed to be on the future, as “a chaotic Iraq is not in anyone’s interests—not in the interest of the Iraqis, not in the interests of the region, and not in the interest of a single member of this organization.”

4

4

Vieira de Mello’s family was divided over where he should be buried. A cosmopolitan, he had not lived in Brazil since he was a boy, but his pride in his nationality had intensified over the years. His mother, Gilda, was desperate for him to return home. Annie proposed that he be buried in her family’s plot in a cemetery near Massongy. In the end the Swiss government extended an invitation for him to lie in rest at Geneva’s exclusive Cimetière des Rois, or Cemetery of the Kings, the small, elegant gated cemetery where Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges was buried and which, eerily, Vieira de Mello and Larriera had visited twice that spring. André Simões, his thirty-seven-year-old nephew, explained the decision to a Brazilian journalist: “His sons said that, as their father was always absent, at least now they would be near him.” Simões’s voice faltered. “It is understandable.”

5

5

Carolina Larriera did not manage to reach Vieira de Mello before he was buried. After traveling to Amman, she attempted to get a connecting flight to Rio de Janeiro in time for the memorial service. But officials in New York were worried that if she and Annie converged, there would be an ugly scene. With a cold formalism that was excessive even by the standards of a gargantuan bureaucracy, they told Larriera that staff rules dictated that the UN would pay only for her to return to her home country of Argentina. She would have to make her own way to Brazil. Larriera flew from Amman to Paris to Buenos Aires and on to Rio de Janeiro, but by the time she arrived in Rio five days after the bombing, still in the torn and bloody skirt she had been wearing the day of the attack, her partner’s casket was gone.The Brazilian 707 had left for Geneva earlier in the day.

Thomas Fuentes, the head of the FBI’s Iraq team, had gathered a wealth of evidence at the crime scene. In the World Trade Center bombing of 1993 and the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995, the vehicle identification number had led the FBI to the terrorists. In Baghdad the FBI had that number, as well as the license plate number and the hand of the bomber.

6

But for all of the encouraging early clues, the investigation quickly stalled. Because Muslim burials typically occur within twenty-four hours of death, Iraq did not have

refrigerated morgues. The only facility available to store the UN’s deceased and the body parts of the bomber had been the air-conditioned morgue at the U.S. base near Baghdad International Airport. But even in the American morgue the temperature often reached 100 degrees because of electricity shortages and overcrowding. As a result, the hand of the bomber, which had seemed a promising source of fingerprints, had begun to decompose. Hoping to preserve it, Fuentes got permission to have it flown back to the United States with the three deceased Americans. But by the time the hand reached the FBI laboratory in Quantico, Virginia, the forensic analysts were able to retrieve only partial fingerprints. And the FBI analysts later learned that Saddam Hussein’s Iraq had never created a fingerprint data bank. Thus, Fuentes had no Iraqi records with which to compare the bomber’s markings. Equally frustrating, he established that the Kamash truck had been made in Russia and purchased by the Iraqi government, probably back in 2001. But despite having its manufacturing and license plate numbers, the FBI was unable to find the vehicle records kept by the Iraqi government—they were presumed to have been looted.

6

But for all of the encouraging early clues, the investigation quickly stalled. Because Muslim burials typically occur within twenty-four hours of death, Iraq did not have

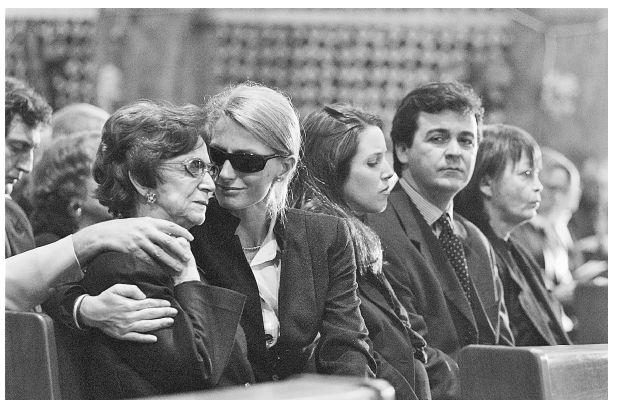

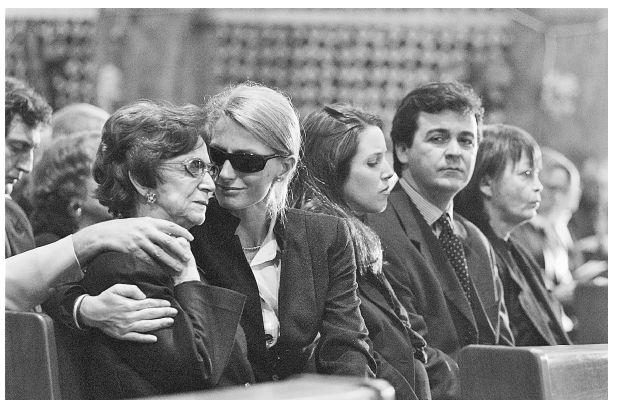

Left to right: Gilda Vieira de Mello, Carolina Larriera, Renata and André Simões, and Sonia Vieira de Mello at a memorial mass in Rio de Janeiro seven days after the Canal Hotel attack.

UN senior staff in New York left the criminal investigation to the FBI and focused on the future of the UN in Iraq. Heated debates commenced about what had become known as the UN’s “perception problem,” the Iraqi belief that the UN was a stooge of the Coalition. Before any long-term decisions would be made, senior staff agreed on the necessity, in the words of one Iraq Steering Group debate,“to reduce the size of the ‘UN target.’”

7

International staff who had survived the bomb were required to take fourteen days of leave, and most would not be sent back.

29

The four thousand Iraqi nationals who served the UN were also granted leave, though they were instructed to take it inside Iraq.

8

7

International staff who had survived the bomb were required to take fourteen days of leave, and most would not be sent back.

29

The four thousand Iraqi nationals who served the UN were also granted leave, though they were instructed to take it inside Iraq.

8

Ghassan Salamé flew to New York, his first trip back since he had accompanied Vieira de Mello to brief the Security Council in July. He told the secretary-general and other senior UN staff that the UN was caught in a catch-22:“If we do not accept increased protection from the CPA, we would be reckless,” he argued. “But if we accept their security, we will reinforce the perception that we are ‘hand in glove’ with the CPA.”

9

The most vocal advocate of withdrawing all UN staff was Kieran Prendergast, the head of the Department of Political Affairs, who was devastated by the death of Rick Hooper. He did not believe that the UN was doing enough good to justify its continued presence in Iraq. “The UN has not been able to establish a differentiated brand,” he argued.“If a fortress is required to ensure security, why be there?”

10

He urged his colleagues to ask a simple question of the mission the UN was undertaking in Iraq: “Is it worth risking the life of one individual?”

11

Staying, he argued, was nothing more than “a suicidal mission.”

12

The downsized UN team that remained in Iraq did little beyond concentrate on securing themselves. Most staff were especially frightened in their hotels at night, and some, Lopes da Silva wrote to UN Headquarters,“were displaying signs of irrational behavior, including requests to carry firearms.”

13

9

The most vocal advocate of withdrawing all UN staff was Kieran Prendergast, the head of the Department of Political Affairs, who was devastated by the death of Rick Hooper. He did not believe that the UN was doing enough good to justify its continued presence in Iraq. “The UN has not been able to establish a differentiated brand,” he argued.“If a fortress is required to ensure security, why be there?”

10

He urged his colleagues to ask a simple question of the mission the UN was undertaking in Iraq: “Is it worth risking the life of one individual?”

11

Staying, he argued, was nothing more than “a suicidal mission.”

12

The downsized UN team that remained in Iraq did little beyond concentrate on securing themselves. Most staff were especially frightened in their hotels at night, and some, Lopes da Silva wrote to UN Headquarters,“were displaying signs of irrational behavior, including requests to carry firearms.”

13

The UN posted twenty-six additional security staff to Baghdad, a dramatic expansion of the tiny squad that had been overwhelmed all summer. Coalition intelligence officers, who had tended to shun UN requests for information on the insurgency prior to the bomb, were suddenly forthcoming. On September 1 they warned the UN that they had intelligence that three heavy sewage trucks had disappeared and one of them might be used to target the UN between September 5 and 10.

14

On September 2 a report

from Erbil, in northern Iraq, said that two vehicles marked UN-HABITAT were missing and might have been stolen and packed with explosives.

15

Later UN officials picked up a rumor in Baghdad that U.S. forces were the ones who had attacked the Canal Hotel so as to drive the UN from Iraq and, in the words of one UN Iraqi staffer, “keep government to themselves.”

16

Although no evidence surfaced to bolster this theory, the Bush administration’s well-established hostility to the UN made it a popular one in the Middle East and in Vieira de Mello’s native Brazil.

14

On September 2 a report

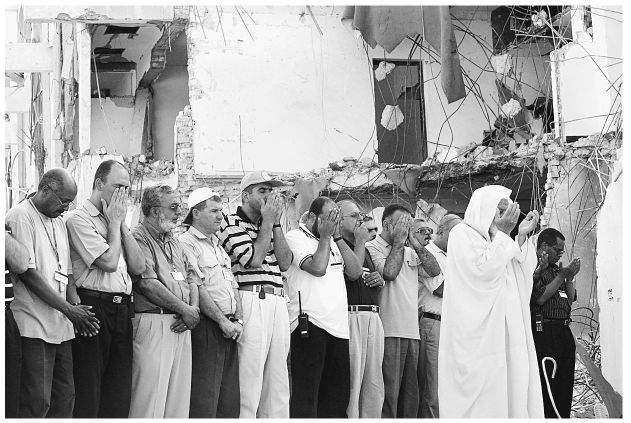

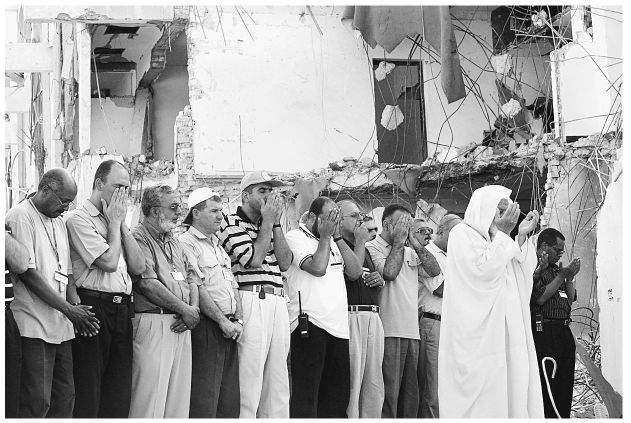

UN staff in Baghdad at a prayer memorial, August 30, 2003.

15

Later UN officials picked up a rumor in Baghdad that U.S. forces were the ones who had attacked the Canal Hotel so as to drive the UN from Iraq and, in the words of one UN Iraqi staffer, “keep government to themselves.”

16

Although no evidence surfaced to bolster this theory, the Bush administration’s well-established hostility to the UN made it a popular one in the Middle East and in Vieira de Mello’s native Brazil.

Other books

The Perfect Lover by Stephanie Laurens

Fire on the Island by J. K. Hogan

The Merchant of Dreams by Anne Lyle

Red Dirt Heart 3 by N.R. Walker

Dying Bad by Maureen Carter

The manitou by Graham Masterton

The Harvest by Chuck Wendig

Devour, A Paranormal Romance (Warm Delicacy Series, Book 3) by Duncan, Megan

Secret Admirer by Ally Hayes