Chatham Dockyard (18 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

Departing from the architectural contributions made by Edward Holl, it is useful to direct further attention to Samuel Bentham. This is because of an additional

contribution that he made to the yard and one so important that, without it, there was every certainty that the yard at Chatham would have been closed and replaced by an entirely new dockyard. Bentham’s achievement was that of overcoming the problem of shoaling and the consequent difficulty of getting ships to the dockyard. First explored as an issue at the beginning of the seventeenth century, it had gained, as already noted, increasing severity throughout the following century and by the year 1800 there was a definite fear that larger ships would be completely unable to reach the yard.

In deciding to construct a considerably enlarged dockyard at Chatham during the early years of the seventeenth century it had been assumed that the river might actually have been gaining in depth. This, of course, had proved itself to be a completely false assumption, with the Navy having to now live up to the consequences of this error. One of the first pieces of evidence to reveal that serious problems lay on the horizon was produced in 1724 by the yard Commissioner, Thomas Kempthorne. He complained that larger ships were unable to move up river other than on a tide that was between half flood and half ebb. As a result of Kempthorne’s concern, a careful survey was undertaken, with numerous soundings taken at various points of the river. In West Gillingham Reach, where a number of larger ships were moored, it was discovered that on a spring tide, the greatest depth of water was 27ft but this fell to 17ft during a neap tide. Even less favourable was the deepest point of East Gillingham Reach where there was only 19ft on a spring tide, this falling to 16ft. As a point of reference, it should be noted that the larger warships of this period generally required a depth of between 21ft and 24ft.

By the 1770s the situation had become even more serious. Instead of ships being able to move up river when between half flood and half ebb, such was now possible only on a spring tide. In other words, ships that were once able to navigate the Medway on tidal conditions occurring twice in every 24 hours, were now restricted to a particular tide that only took place once every lunar month. Furthermore, mobility of shipping on the Medway continued to decline, a survey of 1763 showing that since 1724 the depth of water on a spring tide in Cockham Wood Reach had been reduced by 2ft, while the area between Chatham Quay and Upnor Castle had seen a reduction in depth of 4ft.

As well as presenting a problem for navigational purposes, the increasing shallowness of the Medway also undermined its value as a naval harbour. To allow larger ships to continue using the river for this purpose they had either to be deliberately lightened, to reduce the draft that each required, or ran the risk that the keel or lower hull timbers would suffer damage by scraping the bottom of the river. Neither alternative was acceptable, as a deliberately lightened ship would have timbers that were normally submerged in seawater now constantly exposed to the sun. As a result, the consequent drying process would lead to this part of the ship becoming subject to dry rot.

The problem of mooring ships in the Medway was highlighted in 1771 following an Admiralty inspection of the dockyard and harbour that found:

On enquiry that the depth of water in this port is scarcely adequate for the draughts of the capital ships built according to the present estimates, as few of them can have the proper quantity of ballast on board, and remain constantly on float. The consequence of which is very apparent … [and] which weakens them greatly and makes them sooner unfit for service.

19

Two years later, during a visitation to Chatham, the Earl of Sandwich, in his capacity as First Lord, added:

It must be allowed that this port is not so useful as formerly from the increased size of our ships, so that there are few above five places where a ship of the line can lay afloat properly ballasted.

20

The problem was effectively put on hold until the early years of the following century when John Rennie was requested to view a whole range of problems associated with the further development of the royal dockyards, including that of warships finding it difficult to both navigate the Medway and use these waters for long-term harbouring. Working closely with John Whidby, the Master Attendant at Woolwich, and William Jessop, a consulting engineer, he began to unravel the problem as to why the Medway was subject to such an alarming degree of shoaling. Noting it to be a problem that was not simply restricted to the Medway, they settled upon the notion that it was a result of recent industrial and agrarian developments. Further up river, and beyond where the dockyard was sited, towns and villages were expanding. As they did so, they caused deposits of mud to enter the rivers and feed into the navigable channels and dockyard harbours. Additional deposits also found their way into these same rivers from agricultural improvements and land drainage. Specifically, for the Medway, much of the blame was placed on Rochester Bridge, a point Rennie included in his report:

If Rochester Bridge had been pulled down some years since, and a new one built in the line of the streets through Strood and Rochester, with piers of suitable dimensions, instead of repairing the old one, the large starlings of which act as a dam, and prevent the tide from flowing up to the extent it otherwise would do, the depth of water in front of Chatham, Rochester, and in Cockham Wood Reach, would have been greatly improved. The trustees unfortunately determined on repairing the old bridge. This nuisance still remains and no advantage whatever has been gained. Unless, therefore, something is done to preserve at least, if not to improve the navigation of the Medway, the soundings will go on diminishing in depth and the dockyard will become less useful. In its present state, vessels of large draught of water must have all their guns and stores taken out before they can come up the dockyard and be dismasted before they can be taken into the dock.

21

At that time, Rennie could see no real solution to the problem and favoured construction of an alternative yard at Northfleet, this to replace not just Chatham but also the yards of Woolwich and Deptford.

22

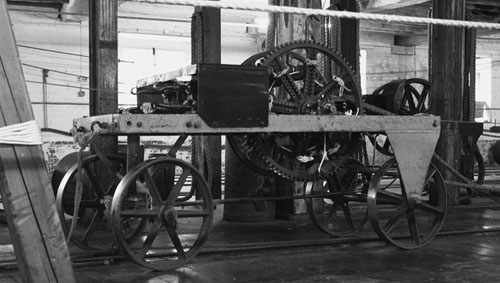

The only drawback, however, was that of the likely cost of such a project, with Rennie suggesting a sum of £6 million. Others disputed this figure, with the Admiralty suggesting that this sum might well double upon construction work getting underway. The project got as far as having outline plans drawn up and the appropriate land purchased. Indeed, the entire Northfleet complex might have been constructed, and Chatham dockyard closed, if it had not been for Samuel Bentham developing a super-efficient dredger through the adoption of steam power. A dramatic improvement on the hand dredgers previously used and operated by dockyard scavelmen, its use resulted in the rapid clearing of many of the problematic shoals. Those hand dredgers had been hopelessly inefficient, removing from the bed of the river no more than a few tons of mud each day. In contrast, a steam-powered dredger based on Bentham’s original design was removing, by 1823, as much as 175 tons of mud per day.

Inevitably, it was Bentham’s development of the steam dredger that saved Chatham from an ignominious closure during the early decades of the nineteenth century. Instead this valuable military complex was not only to continue in its important shipbuilding and repair role but was to enter into a new period of supremacy. Within forty years of those closure threats, Chatham had been earmarked for a programme of expansion that was so massive in scale that it actually quadrupled the land area of the existing yard. Furthermore, it took on its very own specialism through the building of ironclads. Not only was Chatham the first royal dockyard to build an ironclad, but it also became the lead yard when any new class of ironclad battleship was laid down. Although his name is rarely spoken in Chatham, Samuel Bentham was the man who saved Chatham Dockyard – that is, until Margaret Thatcher arrived on the scene some 140 years later.

While Nelson’s original

Victory

is dry-docked at Portsmouth, Chatham can at least lay claim to this model of the same vessel and one which itself has an interesting history having been originally constructed for the Alexander Korda film,

That Hamilton Woman

(1941).

6

The dockyard at Chatham had a much rosier future in the 1820s than it had possessed at any point during the previous fifty or so years. In that earlier period, the yard had even found itself under threat of closure, this a result of the increasing difficulty faced by larger ships attempting to navigate the Medway. With this problem now solved through the introduction of steam dredging, a series of further improvements were under consideration, these designed to allow the yard to both operate more effectively and also to expand upon the work undertaken.

One such project, although dating to the final years of the Napoleonic Wars, was put forward by George Parkin, the Master Shipwright at Chatham. This was in 1813, with Parkin wishing to see a general improvement to the yard’s river frontage, including the various dry docks that occupied this same area. At the time Parkin was concerned with the markedly decayed state of the river wall and a general need to improve and lengthen all of the existing docks. In essence, he suggested a complete rebuilding of the central section of the yard’s river frontage, with part of the wall moved forward several yards and onto an area of land that would be reclaimed from the Medway for this purpose. This would not only have the advantage of increasing the acreage of land within the dockyard, but would allow, at little additional cost, for the lengthening of the two most northerly docks.

The Navy Board appears to have been favourably impressed with Parkin’s scheme, choosing to employ John Rennie, the leading engineer of the age, to undertake a feasibility study. Despite a clear statement that Rennie was only to give his opinion on Parkin’s projected improvements to the dockyard river frontage, the engineer devoted most of his attention to a number of alternative ideas for the general improvement of the entire yard. These were presented to the Admiralty during the summer of 1814, with Rennie both outlining the general defects of the yard and how these might be overcome.

In his report, and given that the problem of silting was at that time unresolved, Rennie not unnaturally devoted a fair amount of attention to this particular issue. In addition, however, he also drew attention to other weaknesses in the usefulness of the yard, these relating to the limited value of some of the existing building and repair facilities together with a general lack of storage space. With regard to the former, he specifically drew attention to the dry docks, these having seen no substantial improvements since the beginning of the previous century. Built for warships of an earlier age, they did not have

sufficient depth for the accommodation of the much larger warships that were now regularly being brought to Chatham. According to Rennie’s calculations it was the Old Single Dock that had the greatest depth of water, this being 18ft 3in on a spring tide and 14ft 9in with a neap tide. Yet, with that additional depth acquired at the height of a spring tide, this dock still required a further 3ft of water for a first rate to make an unobstructed entry. As it happens, such vessels were brought into dry dock at Chatham, but to do so these ships had to be heaved on to blocks that were often 3ft above the base of the keel.