Chatham Dockyard (20 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

I propose to make a new channel or cut for the River Medway, from the bend below Rochester Bridge, opposite Frindsbury Church to Upnor Castle, forming a regular sweep, that it may join in an easy curve with the head of Cockhouse [sic] Reach, and to throw a dam across the old channel, from the north-east corner of Rochester Marshes to the Frindsbury side between the two shipyards, and another across at the north end of the dockyard and above the Ordnance floating-bridge, thus making the old river between the north end of the dockyard and the north-east point of Rochester Marshes into a wet dock, which, taking the surface covered at low water, will be upwards of 150 acres, leaving a space of land between the new proposed cut and the present channel of the river, on the Frindsbury side, of nearly the same extent, and which I proposed shall be purchased and taken into the dockyard.

At the northern end of the dockyard I propose that a new cut shall be made from the dock I have described, across Frindsbury to Gillingham Marshes, south of the line of St Mary’s Creek to the head of Gillingham Reach adjoining the fort, and at its lower end I propose a lock to communicate with the Medway, having a small basin at the head for the convenience of vessels going into or out of the dock or Medway.

7

A secondary advantage to the scheme, and referring to the hazards of navigating the river, was that in creating the new cut, the river would be considerably straightened, so allowing a greater quantity of tidal water to flow and ‘deepen the river between the head of Gillingham Reach and Long Reach, and thereby further lessen the difficulties and detention in the navigation of these reaches’.

8

The Admiralty, for its part, was not sufficiently impressed. Noting that it would require a quite considerable financial outlay, they looked to a much cheaper, if less imaginative, approach to an overall expansion of the existing facilities at Chatham. In rejecting the idea of extending across the river, various purchases of marshlands immediately adjoining the dockyard and within the parish of Gillingham were undertaken. Formally authorised by Act of Parliament, these purchases included Fresh Marsh (18 acres) and Salt Marsh, the marshlands variously owned by Elizabeth Strover, Samuel Strover and John Simmons. The intention at this stage was to use these parcels of land for timber storage and depositing mud dredged from the river Medway. Later, however, this same land formed the basis for a further extension of the dockyard as carried out later in the century.

Concurrent with these significant changes to the yard was that of the provision of roofs to the new docks and slips. The value of roofing was outlined to the Admiralty in a report

of 1817 in which it was claimed that in building and repairing ships under cover there would be a much diminished threat of dry rot. The report went on to suggest that the measure ‘should take precedence over all other objects because there is none other to compare with it as so immediately and permanently affecting the public purse’.

9

By the time of that report, and providing some of the evidence for the necessity of covering all of the yard’s docks and slips, both the No.1 Dock and the second slip had already been covered, a procedure that had been carried out in 1817. While the various docks were given coverings in the manner of an open-sided timber structure with a pitch copper-covered roof, those given to the slips were much grander. For one thing, they had to rise to a much greater height; this to give sufficient clearance to the entire hull that was building on a slipway that was at ground level. The estimated cost for the work of constructing these two covers was £1,165, but to this was subsequently added the sum of £5,630 for the coppering of the two roofs. The covering given to the No.2 slip not only rose to a considerable height but swept out grandly on each side, this to provide a sheltered working area for those employed on constructing new vessels. Unfortunately this particular slip cover was destroyed by accidental fire in 1966, but it had much in common with the covering placed over the No.3 Slip in 1838. The adjoining Nos 4, 5 and 6 slip covers, also extant, are very different in style. Designed by Captain Thomas R. Mould of the Royal Engineers, they are of cast- and wrought-iron construction with a corrugated ironclad roof. The final slip to be covered at Chatham, the No.7, was a considerable further advance in design. Authorised in 1851, it was designed by G.T. Green. Another work constructed from iron, it incorporated travelling cranes operating on rails built into the roof structure.

Holding its first service in July 1808, the Dockyard Chapel provided a discrete place of worship within the yard. Prior to its construction, officers of the dockyard, together with those artisans who chose to attend religious services, had to direct themselves to St Mary’s, the parish church on Chatham Hill (Dock Road).

In the ropery, during the 1830s, steam power began to be introduced. But it had been a long time in coming. In fact, it should have been introduced in 1811, the year in which jack wheels, originally designed to be powered by steam, were first introduced into this area of the yard. Used in the process of laying the strands together to form (or close) the rope, five in number had at that time been purchased from the Henry Maudslay Company. Despite this, the Navy Board at that time had failed to

support the purchase of the supporting steam engine, resulting in these expensive and intricate devices having to be operated manually. Not until 1836 was this ruling overturned, with the sum of £2,500 placed in that year’s naval estimates and earmarked for the purchase of a 14hp steam engine to be manufactured by Boulton & Watt. To provide the necessary accommodation, the hemp house adjoining the north wall of the ropery was to be partially demolished and replaced by an engine house.

10

The arrival of this machinery was to completely revolutionise the process of rope making at Chatham. On the laying floor it immediately reduced the necessity of employing such a large proportion of the workforce during the final closing of the heavy ropes. Furthermore, it paved the way for the introduction of much larger and heavier jack wheels, these more able to handle the heavier ropes. Brought to the ropery during the 1850s, these particular jack wheels were constructed to run on newly introduced sets of rails that ran the length of the laying floor. At the same time, thought was given to making greater use of steam power, with a second engine providing power for the process of hatchelling and spinning, a series of spinning jennies installed on the top floor of the remaining hemp house. This machinery, which required of the operators only limited skills, saw both the hatchelling and spinning processes undertaken by semi-skilled labour together with part-trained spinner apprentices. They in turn were themselves to be superseded, the work of spinning given over to women in 1864.

The employment of women in the spinning process was not the first employment of female labour in the dockyard, women having been employed in the colour loft, manufacturing flags, since the end of the eighteenth century. However, there was a distinct difference between the two groups, with employment in the colour loft restricted to the wives and daughters of those either incapacitated or killed in naval service. As a result, those employed in the colour loft were treated with a good deal of respect and were referred to as ‘the ladies of the colour loft’. The newly employed females entering the ropery were not accorded this same level of respect, referred to as ‘the women of the ropery’. This reduced level of status resulted, in part, from their social background, not being widows or daughters of those in Admiralty service. In addition, less value was placed on the work they were performing, especially when compared with the skill of producing an intricately patterned flag, the ropeyard workers seen only as machine minders. In keeping with nineteenth-century views of morality, the women were strictly segregated from the men, with female employees having separate entrances, staircases and mess room. They also worked different hours, so as to enter and leave the yard at different times to their male counterparts. The only contact with a man was that of their overseer. As for the reason for the introduction of women in the ropery, this was strictly an economy, it being possible to pay them less than men.

Hand in glove with ensuring that the facilities in the dockyard and those employed were fit for purpose was that of also ensuring managerial efficiency. Of particular note was that the resident Commissioner had only limited authority, in that he merely served as a link between the Navy Board and the dockyard. In addition, there was the notable surfeit of officers, at both the principal and inferior levels, with many undertaking tasks

that could easily be merged and performed by a single appointee, rather than two. In 1822, a partial attempt at reform was undertaken when the duties of the Clerk of the Ropeyard were absorbed by the Storekeeper and those of the Clerk of the Cheque by the Commissioner. In one sweep, therefore, two of the more senior posts in the dockyard were removed, with an immediate annual saving of several hundred pounds.

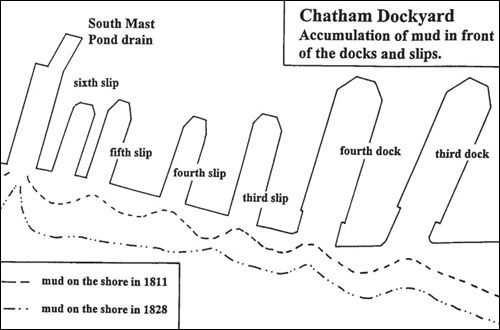

A problem that had to be confronted during the early years of the nineteenth century was the slow strangulation of the dockyard by large quantities of mud that was accumulating in the Medway. The rapidity of its accumulation can be appreciated by this comparison of mud in front of the dockyard in 1811 when compared with 1828.

The reforms of 1822 had also seen abolition of a number of trade masters together with foremen of trades and quartermen. Quartermen had been attached to gangs of twenty working shipwrights and had been responsible for ensuring the quality of work performed. They had taken their instructions from one of the foremen of the yard. However, in abolishing this one group of inferior officers, another group of officers replaced them, these officially known as leading men.

11

They differed from quartermen in respect of being raised workmen who carried out the same tasks as those overseen. At the same time, the number of yard foremen was increased, these officers being relieved of clerical duties that they might be more proactive in the inspection of working gangs. Both the removal of quartermen and the introduction of leading men proved controversial, not least from one outspoken anonymous critic, possibly a clerk employed at Chatham Dockyard, who forwarded a printed volume of his views to the Board of Admiralty:

[It is] with extreme concern that I find so respectable and useful a body of officers abolished; and the places supplied by an inferior class, denominated leading men. Each [Leading Man] has charge of ten working men; whose workmanship he must superintend the due execution of; the stores for whose use he must draw (that is obtain officially from the storehouses) and have the charge of; as also of whatever conversions of materials may be required for him to attend to (so that no wasteful expenditure of the one, nor improper conversions of the other may take place). At the same time, that all these important duties, are required from him (for which additional duty he is allowed only six pence per diem extra) he is to perform the same quantity of work, as each of his men, or otherwise, will be paid as much less, as his work may fall short thereof.

12