Chatham Dockyard (30 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

The delays in delivery of armour plating appear to have caused insuperable problems for the early completion of

Majestic

. The result was that

Magnificent

was not only launched before

Majestic

but a total of forty-three days separated the two occasions. Without doubt, therefore, Chatham had won the first part of the race – the race to get the two battleships into the water.

The final part of the race, completion, continued to be enthusiastically supported. At both Portsmouth and Chatham, it was fully intended that the vessels should be out of dockyard hands by the end of the year, so setting a record for both yards. On board

Majestic

, following an initial flurry of activity, during which the main engine and masts were shipped, something of a lull set in during March. Again, this was no fault of Portsmouth, but the result of a non-delivery of boilers. Once these arrived, so it was confidently reported in the pages of

The Naval and Military Record

in April, ‘the energies of the builders will be considerably increased’. At the same time, delays were also taking place at Chatham, a result of severe cold weather and the freezing over of the fitting-out basin.

By spring, the race to complete both ships was again in full swing. Chatham yard was first to get the 6in gun casements fitted, this completed by the end of June. Not surprisingly, there was a certain amount of rejoicing, this reflected by the resident Chatham journalist of the

The Naval and Military Record

:

So overpowering is the desire to score over the

Magnificent

that the turn-tables have been placed on board without having been taken to pieces – incomplete as they are. It need scarcely be added that the corresponding work is already complete on the

Magnificent

, the forward and after barbettes are ready for mounting the 12-inch guns as soon as they arrive from Woolwich.

18

However, this fine fellow was soon forced to regret these particular comments, the long-awaited barbettes for the 12in guns seemingly having disappeared. At the very least they had still not arrived by October, leading to a suspicion that Portsmouth was receiving undue favouritism:

During the process of manufacturing the gun shields for the

Magnificent

, one of the foremen of the Yard made five or six visits to the contractor’s works to ascertain if the order was being carried out according to the moulds and drawings, and to ensure that no alteration would be required on their arrival; but, although they were to be sent to Chatham, the contractors, for some reason not yet explained, delivered them to Portsmouth.

19

Despite this setback for

Magnificent

, both ships were able to undertake their sea trials during the latter part of 1895, with these vessels both commissioned into naval service on 12 December. Although a contrived end to the race, it was the only fair result. Such competitions were quite meaningless. Whether one yard was in a position to launch or complete before another (or even at the same point in time) was entirely dependent on materials outside the dockyards. Furthermore, such races did not really help create efficiency, they merely caused delays elsewhere. For a dockyard such as Chatham to have a

fifth of its workforce dedicated to the building of one ship meant wholesale delays elsewhere in the system. While the Navy might receive one leviathan earlier than expected, it had to suffer endless delays upon other vessels entering the yard for repairs and refittings. Instead of a smooth and balanced work programme, such a meaningless competition resulted in the wholesale movement of hundreds of men in a frenetic round-about that had nothing to do with the true needs of the Navy.

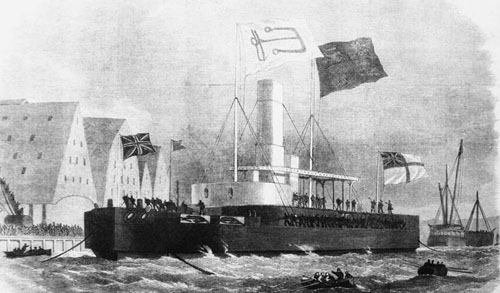

Glatton

, laid down at Chatham on 10 August 1868 and having been built in dry dock, is here seen on the occasion of her floating out of dock, this taking place on 8 March 1871. A particular feature of this illustration is that of it including the various covered slips of the yard, with the No.7 Slip nearest to where the artist is viewing the scene, while Nos 6, 5, 4 and 3 are sequentially located beyond.

The changing nature of ship construction and the Admiralty’s increasing desire for efficiency naturally had an impact upon the workforce. Much of this was fostered by a growth in private capital investment into the shipbuilding industry, with the government dockyards often forced to compete for the purpose of acquiring the right to continue building ships. The competitive construction of the two ‘Majestic’ class battleships was not unconnected with this changing situation, as was the considerable reliance upon outside contractors. In an earlier age, the naval yards would have been virtually self-contained, able to manufacture all of the materials required for construction of a new ship. While this was no longer the case, the private sector having achieved for itself a secure position with regard to the manufacture of armour plating and many other heavy items of equipment, it was to the naval dockyards that new and experimental construction work was reserved. But to compete, the earlier practice of retaining an inflated workforce, sometimes treading water until an international situation brought on a sudden urgency, was most certainly abandoned. The proportion of hired men, those with no permanent contract and open to immediate dismissal, was increased, while even those on the establishment also found themselves open to dismissal during times of austerity. The late 1880s proved particularly horrendous, with hundreds of labourers and artisans discharged and the Medway Board of Guardians being overwhelmed by requests for help. Mavis Waters refers poignantly to one particular episode that took place in September 1887:

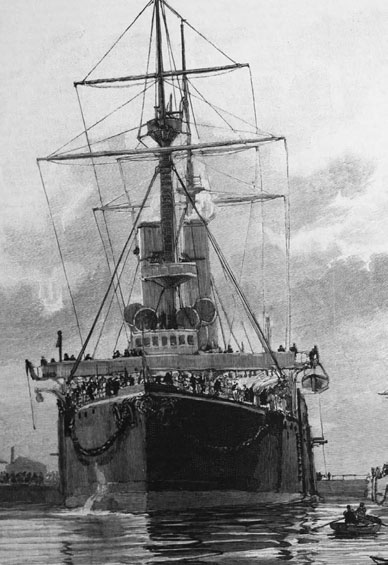

A Chatham-built battleship,

Barfleur

, is here seen in June 1894 leaving the No.3 Basin, passing through the North Lock, following her completion. Weighing in at 10,500 tons, her main armament was that of four 10in guns. Laid down in October 1890 and launched in August 1892 she had subsequently been brought round from the No.7 Slip, upon which she had been constructed, to the extension on St Mary’s Island for a completion programme that took just under two years.

Magnificent

, winner of the race against Portsmouth to be the first to launch a ‘Majestic’ class battleship, is seen here as she prepares to depart Chatham following her completion. Overall, from laying of keel to finally getting the two vessels to sea, the Admiralty inspired race between Chatham and Portsmouth yards was deemed a tie.

Confronted with a woman who wanted assistance for herself and her family while her discharged husband was away in search of work, they [the Medway Board of Guardians] consulted in hushed tones about the possibility of giving out relief, officially prohibited, in the special circumstances of that winter; ‘We are sure to have a number of cases of this kind’, said the Chairman … ‘I am sure the members will not wish to smash the homes up … we have not begun to feel it yet.’ ‘Have a thousand men been discharged?’ asked the Reverend Whiston, ‘Over a thousand,’ replied Councillor Breeze grimly.’

20

According to Waters, this particular crisis, which had passed by January 1889, had a profound effect upon the dockyard workforce. No longer were they prepared to put their trust in the protection of the Admiralty, something that in the past had brought them relatively secure work and the removal of occasional grievances. Organisationally, therefore, they had tended to veer away from involving themselves in nationally organised unions, creating for themselves a number of local associations. These had proved quite incapable of fighting their corner during that crisis period, with the artisans and labourers at Chatham dockyard beginning to look at the means by which those in the private sector were bargaining with their employers through membership of trade unions. Over the following decades, those employed in the various yard trades began to take out union subscriptions, with shipwrights ensuring that the national Amalgamated Society of Shipwrights rapidly replaced the dockyard-based Ship Constructive Association.

21

9

It was the launch of HMS

Dreadnought

at Portsmouth on 10 February 1906 that brought an end to Chatham’s battleship-building pretensions. Controversially it was stated that Chatham was without the space and facilities to launch such a large ship, but this was always disputed by many of those who worked in the yard. In doing so, the older hands of the yard were often heard to argue the case in later years. And they had a point. Both the No.8 Slip, built adjacent to the north of the existing slips and completed in 1900 together with the No.9 Dock, built a few years earlier and annexed to the No.1 Basin, were both of a size that might easily have accommodated

Dreadnought

or one of her sister ships.

At the time of its construction, the No.9 Dock was the largest in the world, having a length of 650ft and a working breadth of 84ft. To support work upon ships being carried

out within the dock, both sides of the new facility possessed gantries for a 20-ton crane while nearby the No.9 Machinery Shop was added very shortly afterwards. As for the No.8 Slip, this was much larger than most other slips of this period, being 616ft in length and specifically designed for construction of large battleships. Due to that policy reversal, based on the supposition that battleships were now too large to be built at Chatham, the No.8 Slip witnessed the construction of only one such vessel. This was

Africa

, a battleship of the ‘King Edward VII’ class displacing 16,350 tons. Entering the Medway on 20 May 1905, she was launched by the Marchioness of Londonderry but not without a small amount of difficulty. On the chord being severed that then released two heavy weights that should have knocked away the dog shores, the vessel failed to move. Even upon the deployment of two hydraulic presses, each capable of moving 200 tons, the ship remained static. Finally, a lift frame hydraulic ram, exerting a pressure of 1,000 tons, managed to achieve the desired effect and sent the vessel into the water.