Chime (24 page)

Perhaps he’d worn me down.

And now I was speaking to him, although it was yet another betrayal of Stepmother. I’d already betrayed her in so many ways. Going into the swamp, frolicking about rather than working out how to apprehend her murderer.

Out we went, the Brownie and I, into the snarl of time, twisting and tangling through the village to Dr. Rannigan’s house.

His housekeeper said he was attending another patient.

“Do you expect him back soon?” I said.

His housekeeper was sure she didn’t know.

“Might he have stopped at the Alehouse?”

His housekeeper said it was not her place to remark upon the doctor’s attachment to the demon drink, and that I might perhaps take myself off, as she had work to do.

“How dare he!” I said to the Brownie, which made no sense, but the Brownie, being the Brownie, understood. Dr. Rannigan was our Dr. Rannigan. We needed him now.

I sat on a stile outside the doctor’s house and waited. The Brownie waited, crouched at my feet. “I missed you,” I said.

“It were a worry, mistress, when tha’ setted tha’ lips an’ didn’t say nothing.”

I missed you.

What had made me say that? But it was true, especially in the last few months of Stepmother’s life, when she grew worse and I grew better.

What had made me say that? But it was true, especially in the last few months of Stepmother’s life, when she grew worse and I grew better.

“But I’m afraid,” I said. “We could easily hurt someone again.”

I saw the world those last few months as though through a magnifying glass. The world shrank to a three-inch circle. It was reduced to bits of lint and flakes of paint and nibblings of fingernails.

“But mistress,” said the Brownie. “Us never hurt nobody.”

“That’s what I thought,” I said. “But I know differently now.”

“But mistress!”

I slid from the stile. I didn’t want to speak of Stepmother and Mucky Face. “Perhaps Dr. Rannigan’s finished with his patient.”

I knew what kinds of arguments the Brownie would offer; I’d offered them all myself. I hadn’t the patience for them now. The day was taking forever. Where was the loose end of time?

The Brownie and I peered into the Alehouse. No Dr. Rannigan.

He was at none of the usual places. He wasn’t playing at draughts with the mayor; or discussing herbs with the apothecary; or in the teashop, reading the

London Loudmouth

. We returned to Dr. Rannigan’s house and peered in the garden shed. His guns were still hanging from the wall. So he wasn’t out shooting pheasant, although hunting season had just begun and Dr. Rannigan loved to hunt.

London Loudmouth

. We returned to Dr. Rannigan’s house and peered in the garden shed. His guns were still hanging from the wall. So he wasn’t out shooting pheasant, although hunting season had just begun and Dr. Rannigan loved to hunt.

Back to the Alehouse, where Dr. Rannigan and Cecil sat sharing a table and a plate of fried fish. Cecil saw me first.

“Milady!” One coiled-spring move, and he stood before me. He was stronger than I’d thought, faster than I’d thought.

“Not now, Cecil. I must speak with Dr. Rannigan.”

“But Briony—” Cecil blocked my way.

“Let me pass, Cecil.” I was shouting. “Let me pass!”

All at once I was looking into Dr. Rannigan’s patient cow eyes, holding his hand, walking with him through the Alehouse door, hearing him tell me to stay in the Alehouse, to sit and rest. Hearing him tell me I looked tired. Watching his rumpled back cross the square—

The world leapt back to its mad pace. The day had passed while I wasn’t looking. Shadows leaned against the windows, candles sprang into flame.

“Milady!”

I turned my back on Cecil, rounded the corner of the Alehouse. But that was stupid, because there was only more Alehouse. No part of the Alehouse is safe if one is to avoid Cecil Trumpington.

“Please talk to me!” Cecil’s voice came pleading and scratching at my back.

We’d rounded into a sprinkle of outdoor tables, where eel-men were fortifying themselves for nightfall. The eels were running, and eels are best caught in the dark.

“Please! I shall go mad otherwise.”

I sat at the nearest table; I couldn’t be bothered to care, not about Cecil. But the thought of eels wriggled its way into my mind. Eels, sent to inland cities; eels, smoked or jellied or simply made into soup. Any method will do for those of homicidal disposition. Just add your favorite poison. It will never be detected beneath the taste of eel, which is so, well, eel-ish.

“I’m awfully tired,” I said. “Can you be quick about it?”

Poor Cecil, consumed by a

grande passion

, only to be told to compress his love manifesto into a haiku.

grande passion

, only to be told to compress his love manifesto into a haiku.

“I won’t try to excuse my behavior,” he said. “It was despicable.”

Or a limerick.

There once was a rotter named Cecil,

Whose Love Interest wished he could be still.

Oh well. Unlike some, at least, I’ve never pretended to be a poet.

Cecil clutched at his hair, although he would undoubtedly prefer that his biographers describe him as having

rent his hair.

The effect was not unattractive. “I can’t explain what came over me.”

rent his hair.

The effect was not unattractive. “I can’t explain what came over me.”

“I can.”

He rent his dark tresses,

Resulting in messes,

Thus prompting his L.I. to flee till,

she reached the end of the world and jumped off.

Perhaps I have untapped potential.

“You do understand! You know how it drives one mad.”

“What does?”

“Unrequited love,” said Cecil.

“Unrequited lust, you mean.”

“It’s no such thing!”

“Really?” I said. “I can hardly take that as a compliment.”

Cecil’s tongue stumbled over itself, trying to explain the fine distinction between passion and lust—

“And drink,” I said.

“Briony, please.” Cecil reached across the table.

My hand jumped away of itself. “Don’t touch me!” My voice went funny, making us both pause and lean back.

Cecil broke the silence. “Are you afraid of me?”

“Would you enjoy it if I were?”

Of course I wasn’t afraid. I’d been afraid on Blackberry Night, but only in a primitive, reactive sort of way. The startle-fear of tripping on a stair, or hearing a noise in the dark.

What could Fitz possibly have seen in him? They spent such a quantity of time together.

“Whatever did you and Fitz talk about?”

Cecil blinked, twice, as though that would help him catch up with the conversation. “We were drinking mates. We didn’t talk much.”

“You can’t drink and talk at the same time?”

“Oh, I showed Fitz a few things,” said Cecil. “He’s older than I, but less experienced in the ways of the world.”

Fitz, less experienced? Fitz, who’s been to Paris and Vienna? “What ways?”

“I don’t want to talk about Fitz,” said Cecil. “I want to talk about you, about us. First Eldric came, and now you’ve changed.”

“You’re the one who’s changed.” I showed him the pale underside of my wrist, the bruises left by two fingers and a thumb.

If there were such a thing as a vampire-puppy-dog, it would be Cecil. Big pleading eyes, asking for an ear-scratch and a nice warm bowl of blood.

“Why don’t you have any bruises?” I said. The vampire-puppy-dog looked all about.

“Eldric hit you hard.”

“He hit me where you can’t see,” said Cecil at last.

Where you can’t see? Most satisfactory!

“Forget Eldric,” said Cecil. “I was useful to you, admit it.”

“Useful?” I said. “How do you mean?”

“Are you back to that game?” His eyes went narrow and chilly. Terrifying, I’m sure. “Pretending you never took me into your confidence about it.”

“We’d get on better,” I said, “if you could tell me what the

it

is.”

it

is.”

“I’d never have thought it of you,” he said. “I did it out of love.”

Either I was mad, or Cecil was mad. I am not the sort of person to go mad, so the honors go to Cecil.

“Look at you,” said Cecil. “That angel face, that lying tongue.”

“What can I say to convince you that I’m utterly in the dark?”

“You could start with the truth,” said Cecil.

What a fine bit of irony: I tell the truth for once, but am thought to be lying. “Just tell me, Cecil! Then we’ll have something concrete to talk about.”

Cecil shouted; his head and shoulders came at me across the table. I startle-jumped away, rammed into the back of the chair. It wasn’t real fear, just the startle-fear that helps you run fast when there’s danger about.

I rose. “I can’t talk to you when you act like a spoiled child.”

“You mind your tongue!”

“Oh, I do,” I said. “I sharpen it every evening on your name.”

“I could make things hot for you.” Cecil’s lips were bloodless. “I could make you squirm.”

My hands were shaking. “Are you threatening me?” I clasped them behind my back.

“What if I am?”

What a stupid question. “Then I shan’t bother to stay.” I walked off, but he shouted after me.

“I’ll expose you, I swear I will. You don’t believe I will, but just you wait. One of these days, there will come a knock at the door, and what will you think when you open it to see the constable on the other side?” And more of the same, much more.

I was halfway across the square before he stopped shouting.

Dr. Rannigan had come and gone, leaving gloomy news and gloomy fathers. I found it hard to attend to what Mr. Clayborne told me. I felt as though I were listening to him through the wrong end of a telescope. My startle-fear still hung about, which was distracting.

Go away!

I told it.

I don’t need you anymore.

Go away!

I told it.

I don’t need you anymore.

“Pearl told me something,” I said. “She says Leanne’s visits tire him.”

There! I’d achieved one happy result. No visits from Leanne, for the present. Not until he improved. Mr. Clayborne himself said so.

And still the startle-fear hung on. It had outlived its purpose, which was to help a person spring into action, spear the woolly mammoth, stake the vampire-puppy-dog. But it didn’t help a person understand how she caused Eldric to fall ill. If I knew how I’d done it, perhaps I could reverse it.

I don’t need you any longer,

I told the startle-fear.

I told the startle-fear.

It didn’t care.

You’ve become a nuisance.

It didn’t care.

You are no longer adaptive. Have you never heard of Mr. Darwin?

It hadn’t.

Ignore it, Briony. You shall have to adapt instead. Think! Stepmother was ill; Eldric is ill. Eldric looks just as Stepmother did, like an egg without a yolk. Stepmother fell ill because you called Mucky Face, and Mucky Face injured her spine. Eldric fell ill because—because why?

What did I do?

Dr. Rannigan confessed to being astonished. How could Eldric have made a full recovery in only two days? This had been the damndest season for illnesses, he said. The swamp cough comes and goes. The egg-with-no-yolk illness comes and goes. He didn’t know what the egg illness was, mind you. He’d seen it only in our family. When Father grew ill, when I grew ill. Eldric’s case reminded him particularly of the late Mrs. Larkin’s illness, how with her too the disease came and went. Her decline was slower than Eldric’s, but she’d surely have died of it if there hadn’t been, oh, you know, the unfortunate incident with the arsenic.

I heard Eldric come down the corridor to the library. It’s astonishing that one can recognize a person merely by the way his shoe meets the floor. Now his hand touched the library doorknob, now the door whispered across the carpet. “It’s dark in here.”

I’d left the lamps dark in case my face betrayed me. I wasn’t as sure of my Briony mask as I’d once been. Rain rattled at the windows, coals spat in the hearth. I sat on the carpet, in the shadows. I reserved the spatter of firelight for Eldric.

“You’re looking very well,” I said. One couldn’t say the roses had come back to his cheeks—he wasn’t a pinkish person—but he’d gone gold again.

You’re looking very well.

How stupid you sound, Briony! You speak just as Father might.

How stupid you sound, Briony! You speak just as Father might.

“I am entirely well,” said Eldric, “which has Dr. Rannigan exploring first one theory, then another, trying to understand. But not being a man of science, I don’t care about understanding. I simply want to go outside and break a few windows.”

Say something, Briony; say something! The Briony mask always had something tart or amusing to say, but the underneath Briony could think of nothing. The clock tut-tutted in the silence. How slowly it spoke, so slowly that between tick and tock came the sharp silvery plink of rain on glass.

“I’m glad you’re better,” I said, which was trite but true.

Better, he was better! As soon as I said the word, I felt relief. For once in my life, I felt relief. It came as a melted-butter drizzle down the back of my legs. It pooled in my knees. Perhaps that’s why people’s knees grow weak.

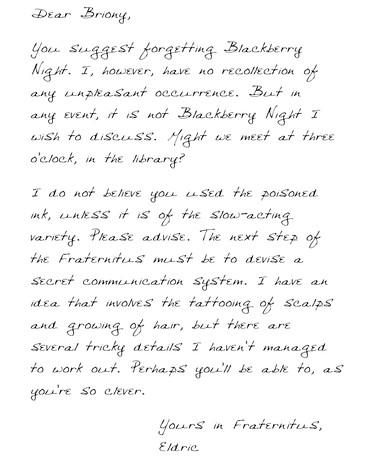

“I was a little dishonest with you,” said Eldric. “In order to tell you what’s on my mind, I have to bring up Blackberry Night.”

Other books

On a Scale from Idiot to Complete Jerk by Alison Hughes

Foreign Agent by Brad Thor

Jakob’s Colors by Lindsay Hawdon

Unnatural Exposure by Patricia Cornwell

Finding Abbey Road by Kevin Emerson

Ruby by Lauraine Snelling, Alexandra O'Karm

The Art of Becoming Homeless by Sara Alexi

Unknown by User

The Promised One by David Alric

War Torn Love by Londo, Jay M.