Chinese Comfort Women (16 page)

Read Chinese Comfort Women Online

Authors: Peipei Qiu,Su Zhiliang,Chen Lifei

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social Science, #Women's Studies

It is not known how many Chinese comfort women were killed during the war. As we observe in this book, only an extremely small number survived, and the majority of these were ransomed by their family, rescued by local people, or escaped before the war ended. Investigations into the fate of Korean comfort women suggests that 75 to 90 percent of them became war casualties.

30

The casualty rate for Chinese comfort women is likely even higher. During the six years that the Japanese military occupied the Hainan region, for example, it built approximately 360 strongholds on the island and over three hundred comfort stations to service its troops.

31

These comfort stations were generally staffed with ten to twenty comfort women, but the larger ones, such as the Basuogang Comfort Station and the Shilu Iron Mine Comfort Station, each held as many as two to three hundred women.

32

Researchers estimate that, in Hainan alone, over ten thousand women were confined as

sex slaves during the occupation;

33

these included women drafted from Mainland China, Korea, Taiwan, Japan, the Philippines, and Singapore, but most were Chinese women drafted locally or from the southern provinces of China. Thus far only forty-two survivors have been found in the region. According to the testimonies of twenty survivors who were available for interviews,

34

eleven of them survived because they escaped from the comfort stations, two were rescued by family members, three were bailed out by local leaders, and only four were freed after the comfort stations were abandoned at the end of the war.

35

The preceding pages provide an overview of the military comfort women system, from its early stage during Japan’s aggression in Manchuria and Shanghai in the early 1930s, to its rapid expansion after the Nanjing Massacre in 1937, to Japan’s defeat in 1945. This information shows the close correlation between the proliferation of military comfort stations and the progression of Japan’s invasion of China. It also provides a glimpse of the sufferings of the women who were forced into these military facilities. However, as Diana Lary and Stephen MacKinnon observe in their examination of the scars of war that mark Chinese society, the scale of suffering during the Second Sino-Japanese War was so great as to almost defy description and/or analysis.

36

The best way to understand the enormity of the suffering of comfort women and the horror of the military comfort stations is through listening to the life stories of the individual victims. The twelve women who told us about their wartime experiences are among a handful of comfort station survivors found in Mainland China. Their narratives reveal, in detail, the brutalization to which Chinese women were subjected and its long-term impact on their lives.

PART 2

The Survivors’ Voices

Figure 6

Locations of the “comfort stations” where the twelve women whose stories are related in this volume were enslaved.

The stories of the twelve comfort station survivors – Lei Guiying, Zhou Fenying, Zhu Qiaomei, Lu Xiuzhen, Yuan Zhulin, Tan Yuhua, Yin Yulin, Wan Aihua, Huang Youliang, Chen Yabian, Lin Yajin, and Li Lianchun – are based on oral interviews conducted by Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei from 1998 to 2008.

1

At the time this book was written, seven of the twelve women had died.

The interview process was extremely difficult for both the survivors and the interviewers. The nature of the torture to which they were subjected in the comfort stations during the war, coupled with the postwar socio-political climates, made it very painful for the victims to speak of their past. In addition, in the rural areas, where most of the Chinese comfort station survivors lived, traditional attitudes toward chastity remain deeply rooted and contribute significantly to the embarrassment and pain experienced in the telling. In Yunnan Province, for example, although there is concrete evidence of a large number of military comfort stations, few survivors are willing to step forward and relate their experiences. People acquainted with the victims also avoid the subject, fearing damage to their relationship with the victim’s family. Li Lianchun, one of the few survivors in Yunnan Province who revealed her experiences as a comfort woman, would not have done so without the support of her children. The psychological trauma and fear of discrimination continue to haunt these survivors, even after breaking their silence. After the war, Yuan Zhulin was exiled from Wuhan City in central China to a remote farm in northeastern Heilongjian Province for seventeen years because it was revealed that she had been a comfort woman for the Japanese military. Even many years later, when she was invited to participate as one of the Chinese plaintiffs in the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery held in Tokyo in December 2000,

2

Yuan Zhulin experienced tremendous anguish the night before her scheduled testimony and said she could not go on stage the next day to recount what the Japanese military had done to her. Chen Lifei sat with her for hours until she finally overcame her pain and fear and gave a powerful speech in the tribunal court. Yet, when a group of legal experts and researchers sought her out at her home in 2001, she would have been unable to go through the account notarization process without professional psychological support to deal with the return of her fear and anguish. In order to minimize the pain of talking about the horrors of the comfort stations, Su and Chen conducted their interviews in locations that were as convenient and as comfortable for the survivors as possible. The interviewers frequently travelled across China to remote villages and walked for hours over rough mountain roads to reach the survivors’ homes.

Three groups of basic questions were asked of each survivor concerning her experiences before, during, and after the Japanese invasion:

1 What was the survivor’s prewar family and personal background?

2 During the war, how did she become a comfort woman? Were there any witnesses? What did the comfort station look like? How was she treated in the comfort station? How did her comfort station experience end?

3 What is her current marital situation? Does she have any children? What are her relationships with her immediate family members, more distant relatives, and neighbours like? Does she think that she has suffered discrimination or political persecution as a result of her comfort station experience? Has she experienced any psychological aftermath? What is her life like currently?

Out of concern for each survivor’s emotional and physical condition, the interviewers refrained from imposing a rigid format and from designating a specific amount of time; instead, they altered the time and direction of the conversation to comply with the needs of each survivor. Therefore, the accounts are uneven in length and format, but all were prompted by the above questions. Some of the survivors were interviewed several times over a long period of time. For example, Su and Chen visited Zhu Qiaomei in her home seven times over the course of five years until her death in 2005. However, due to health concerns, multiple interviews were not possible for every survivor. Su Zhiliang said: “I would not bother these survivors over and over again when I was able to verify the facts of their victimization through one interview, because they told me that each time they talked about their horrible experience, it was as if they were going through the hell again.” Su then added: “It’s very, very painful. Even I myself could not sleep for days after each interview.”

Being sensitive to the condition of the aged survivors, the interviewers carefully verified the accuracy of each woman’s oral accounts by such methods as locating the site of the comfort facilities in which she was enslaved, collecting testimonies from other local witnesses, and comparing her accounts with local historical records (see

Figure 7

). For example, when she was being interviewed, Wan Aihua had trouble remembering some of the details of her abduction due to the trauma it had entailed. However, from the information she provided, such as the plants she saw and the food people were eating at the time, the interviewers were able to approximate the time of year when she had been kidnapped and tortured. After recording her life story, the interviewers drove a long distance to Yangquan Village and found Hou Datu, the owner of the cotton-padded quilt Wan Aihua had used in the comfort station, and obtained his affidavit relating to her torture. With the help of a local volunteer, Zhang Shuangbing, the interviewers also located the cave

in which Wan Aihua was confined and the riverbed where she was first captured. All twelve accounts in this chapter have been verified by such field methods.

Figure 7

The interviewers took a picture of the rock cave where Li Lianchun hid in 1943 after her escape from Songshan “Comfort Station.”

The translation makes every effort to be faithful to the survivors’ words, which are spare but extremely powerful. In order to enhance the flow and readability of the transcripts, the translation omits the interviewer’s questions. The accounts are grouped according to the geographical location of the survivor’s confinement and are listed in chronological order: the eastern coastal region in the beginning of full-fledged warfare; the warzones in central and northern China from late 1939 to 1944, where Japanese military expansion reached an impasse; and, finally, the southern Chinese frontlines from 1941 until the end of the war. Before each survivor’s account, brief background information is provided to help to situate her experiences within a larger historical context of the war. The testimonies of local witnesses are added to the accounts when there is a lapse in the survivor’s recollection, and explanatory notes are provided for terms and events that are unfamiliar to non-Chinese-speaking audiences. Additional information about the postwar experiences of Chinese comfort women is provided in

Part 3

.

5 Eastern Coastal Region

Lei Guiying

At the age of nine, Lei Guiying witnessed the atrocities the Japanese soldiers committed in her hometown in the Jiangning District of Nanjing around the time of the fall of Nanjing in December 1937. At age thirteen, as soon as she began menstruating, she was forced to become a comfort woman for the Japanese military

.

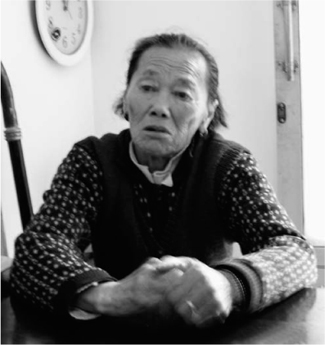

Figure 8

Lei Guiying giving a talk in Shanghai in 2006 to teachers and students from Canada.

I was born in a place called Guantangyan. My father died when I was only seven, so I don’t remember his name. My mother’s surname was “Li” and her parents lived in Shanghe Village. Guantangyan is located on the bank of a river that runs through Tangshan Town.

In the winter of the year after my father’s death, my mother was taken away by a group of people from nearby Ligangtou Village while she was on her way to work. At that time a poor man who could not afford a wedding would snatch a woman to be his wife. At the time I had a five-year-old brother called Little Zaosheng. The men from Ligangtou Village let my mother bring my younger brother with her because he was a boy. I was left behind. My grandparents had already died. My late father had a younger brother in the village, but he was not living with my family. A teenager himself, this uncle was unable to support me, so I had no one to depend on.