Chinese Comfort Women (20 page)

Read Chinese Comfort Women Online

Authors: Peipei Qiu,Su Zhiliang,Chen Lifei

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social Science, #Women's Studies

The day I was kidnapped was an extremely cold day in the Second Lunar Month, when the Chinese New Year was just over. I was taken to the military compound in the Town of Miaozhen, Chongming County. The building was a two-storey house in which were confined over a dozen local young women. I was unfamiliar with most of them. I only knew one girl, whom we called XX the Beggar, and another one named XXX. [The names are omitted to protect the victims’ privacy.]

I was assigned to a room on the lower floor of the building. Each of us girls had a very small room in which there was a bed and nothing else. The building was very close to the military barracks. It was guarded by soldiers, but we were allowed to walk around the facility and do things such as washing clothes. The platoon chief ordered soldiers to watch us and not to let us go too far, and we were not allowed to enter the barracks.

Shortly after I was taken into the comfort station I was raped by many soldiers. My lower body hurt so much that I could neither walk nor even sit. The platoon chief came frequently. He was about thirty years old and wore a sword. He came every two or three days, usually during the day, and

sometimes brought canned food with him. I noticed that the Japanese troops stationed at Chongming often ate canned food. Perhaps they feared being poisoned by the Chinese people; they would not eat any dish made by Chinese cooks before testing it by having a Chinese person eat it first. Occasionally the soldiers gave us a little of the food they brought over, but they never gave us any money. Needless to say, I never dared to ask for money.

As time passed, the platoon chief seemed to have said something to the soldiers and prohibited them from entering my room; so only the platoon chief himself frequented my room. The soldiers resented me very much since they were not allowed to touch me. When the chief was not around, they would retaliate by throwing my clothes up on top of the roof and so on. With no extra changes I had to wear the same clothes all the time and wash them at night. When the platoon chief found out about what the soldiers had done to me, he scolded them. The soldiers stopped bullying me after that, while the platoon chief kept me to service only himself, abusing me viciously.

The big house had a cook who made the meals, which usually consisted of rice and a bowl of vegetables. Sometimes the vegetables were served in small dishes placed in a large box. Labourers in the house were all Chinese. One of the workers was a traitor named Xu Qigou, who supervised the comfort women. His wife worked as the cook, did laundry, and also served meals to the Japanese soldiers. This woman was very mean; she often yelled at us and gave us only a very small amount of food. We were always starving.

The Japanese soldiers did not wear condoms when they raped the women in the station. Occasionally a doctor, who was a Chinese person, gave us physical examinations. I remember the doctor came two or three times and he stuck something into our lower body to check it. I don’t remember if we were given any medicine.

I was kept in the comfort station until one morning in the Fifth Lunar Month that year [1938] when I escaped from that place. It was when the fields turned golden yellow and the villagers were harvesting wheat. I had planned to escape for a long time. That day, when I saw the Japanese soldiers off guard, I sneaked out. I made sure that nobody noticed me then ran without stopping. There was a highway near the comfort station and I knew my hometown was on the south side of it, but I didn’t dare to go back there. Fearing that the Japanese soldiers might come after me by the highway, I didn’t go that way but instead ran along small paths. I ran for a long while without a specific destination until it occurred to me that I had a relative who treated me like a daughter in Shanghai, so I decided to go there.

The trip to Shanghai was hard, but I managed to get a free boat ride across the Yangtze River and to find my relative. She sympathized with me and let

me stay at her place. She also sent a message to my family saying that I was with her. I didn’t return home until a person from my hometown came to tell us that the Japanese troops had been relocated.

Because I had been raped by the enemy, people in my village gossiped about me, saying that I slept with Japanese soldiers. I was unable to find a prospective husband until I was thirty-three years old, when someone introduced me to Mr. Wang, a custodian at Huaihai Middle School in Shanghai. He was looking for a woman to help care for his family after his wife died, leaving him with two young children. I married him, but I was unable to bear children. People in my village believed that a person defiled by Japanese soldiers would bring bad luck and could not produce anything good. They said I could not even grow things well in the fields. I lack education and have no knowledge of medicine, so it’s hard for me to tell if my infertility was due to the damage caused by the Japanese soldiers.

I am so embarrassed talking about these things. These things are so hard to talk about, but my stepson and daughter-in-law have been very supportive and they encourage me to tell the truth and seek justice. I am very old now and I cannot stomach the atrocities done to me any more. I cannot walk, my head is dizzy all the time, and my memory is failing me. I hate the Japanese troops who destroyed my reputation and my life. Japanese troops invaded our country and committed the crimes that caused my misery; whether they admit it or not, that fact cannot be altered. Some Japanese people do not admit the bad things Japanese troops did in the past, but other survivors and I are still alive and we can provide evidence. We will fight to the end!

On 14 February 2001, Shanghai Jing’an District Notary, Shanghai Tianhong Law Firm, and the Research Center for Chinese “Comfort Women” notarized the testimonies of Lu Xiuzhen, Zhu Qiaomei, and Guo Yaying regarding their experiences as Japanese military comfort women. A year later, Lu Xiuzhen died on 24 November 2002. Chen Lifei and Zhang Tingting, from the Research Centre for Chinese “Comfort Women,” attended her funeral, and the research centre sponsored the placement of her tombstone

.

(Interviewed by Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei in March and May 2000, and February 2001)

6 Warzones in Central and Northern China

Yuan Zhulin

When the Japanese forces attacked Nanjing the Chinese Nationalist leaders shifted their headquarters to Wuhan, Hubei Province, then the most populous city in central China as well as a transportation centre. Japanese forces launched major air strikes on Wuhan in April 1938

,

1

and this was followed by a massive campaign in the summer of the same year. Chinese forces committed a large number of units to protect Wuhan. Bloody battles, which involved 300,000 Japanese and 1 million Chinese troops, lasted for months in the region and resulted in heavy casualties on both sides. The defence eventually fell to Japanese troops at the end of October 1938

.

2

The Japanese army continued to press westward and southward after the occupation of Wuhan, but it was unable to completely control Hubei and the nearby provinces. The war in the Chinese theatre was deadlocked. During the seven years of fighting in the region the Japanese military established a full-blown comfort women system in the occupied areas of Hubei. Yuan Zhulin was one of the many Chinese women enslaved in Japanese military comfort stations there

.

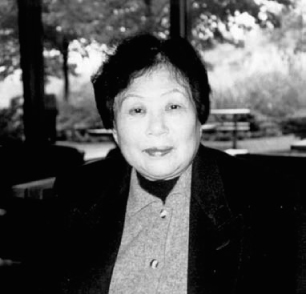

Figure 12

Yuan Zhulin, in 1998, attending a public hearing in Toronto on the atrocities committed by the Japanese military during the Asia-Pacific War.

I was born in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, in 1922, on the Sixteenth day of the Fifth Lunar Month. My father, Yuan Shengjie, and my mother, Zhang Xiangzi, had three daughters. They were very poor and didn’t have the money to send me to school. Unable to support us three girls, my parents sent my two sisters and me to other families, one after the other, to be child-daughters-in-law. My family fell apart and I never saw my sisters again. I married Wang Guodong, a chauffeur, at the age of fifteen. We were not rich, but we loved each other and lived a comfortable life.

However, our peaceful life didn’t last very long. In June 1938, the year after we were married, the Japanese armies launched attacks on Wuhan City. My husband was at work in the faraway area controlled by Chinese forces. I had no place to escape to and stayed home. Not long after my husband left, my mother-in-law began to treat me like an outcast. She thought I was an extra burden on the family and, since her son might never be able to return, she forced me to leave the family and remarry. I felt very humiliated, yet I had no choice but to marry a man named Liu Wanghai. The following year I gave birth to a girl named Rongxian. She was the only child I birthed. [Yuan Zhulin didn’t want to talk about her only daughter at the interview. Later the interviewers found out that the child had died of neglect while Yuan was held as a comfort woman.] Liu Wanghai didn’t have a stable job; in order to help support the family, I worked as a maid, although frequently I could not find a job in the turmoil and economic depression during the Japanese invasion.

In the spring of 1940, a local woman named Zhang Xiuying came to recruit workers. She said that cleaning women were wanted at hotels in the other cities in Hubei Province. I had never met Zhang before, but since it was very difficult to find a job at the time, several other young girls and I signed up. I was eighteen years old then and good-looking, so I stood out among the other girls.

I didn’t know until much later that Zhang Xiuying was a despicable woman. Her Japanese husband could speak some Chinese; following orders issued by the Japanese army, he was rounding up Chinese women to set up a comfort station. I still remember how he looked; he was a man of medium height who often wore Western-style suits rather than a military uniform. He had dark skin and bug-eyes, and people called him “Goldfish Eyes.” He was about forty years old.

I left my second husband, Liu Wanghai, and my daughter behind and travelled aboard a ship down the Yangtze River. In the beginning I was quite happy to have found a job, and I thought it could bring me a better future after the initial hardship. The ship arrived at Ezhou in about a day. As soon as we went ashore, we were taken to a temple by Japanese soldiers. As a

matter of fact, the Japanese army had already turned the temple into a comfort station. A Japanese soldier was standing guard at the entrance. I was frightened by the devilish-looking soldiers and didn’t want to enter. By now the girls and I realized that something was not right, so we all wanted to go home. I cried “This is not a hotel. I want to go home.” But the Japanese soldiers forced us inside with their bayonets.

As soon as we entered the station the proprietor ordered us to take off all our clothes for an examination. We refused, but Zhang Xiuying’s husband had his men beat us with leather whips. Zhang Xiuying yelled at me maliciously: “You are the wife of a guerrilla! You’d better follow the instructions!” [Zhang was likely referring to Yuan Zhulin’s first husband, who worked in the area under the control of the Nationalist Party (Guomindang), which led the fighting against Japanese forces.] The physical examination was over very quickly since none of us was a prostitute and no one had a venereal disease. After the examination, the proprietor gave each girl a Japanese name. I was named Masako. Each of us was assigned a room of about seven or eight square metres that had only a bed and a spittoon.

The following morning I saw a wooden sign hung on the door of my room with “Masako” written on it. There were also similar plaques hung at the entrance of the comfort station. That morning a lot of Japanese soldiers were swarming outside of the temple gate. Soon a long line formed at the door of each room. I … [sobbing] was raped by ten big Japanese soldiers. I became so weak by the end of the day that I was unable to sit up. The lower part of my body felt as if it had been sliced with knives.

From that day onward, I became a sex slave to Japanese soldiers. I heard that each Japanese soldier had to buy a ticket to enter the comfort station, but I never saw how much they paid. I certainly never received a penny from them. The proprietor hired a Chinese man to cook us three meals a day, but the food was very bad and the amount was very small. We girls who suffered numerous rapes every day needed to wash our bodies, but there was only a wooden bucket in the kitchen for us to take turns using. There were dozens of comfort women at the station, so the bath water was unbearably dirty by the end of each day.

Each Japanese soldier usually spent about thirty minutes in a room. We couldn’t get any rest even at night because the military officers often spent a couple of hours, sometimes the whole night, at the station. The proprietor didn’t allow us a break even during our menstrual periods; he continued to let the Japanese soldiers come in one after another. He made us take some white pills and told us that there would be no pain if we took them. We didn’t

know what the pills were. I threw them away like the other girls. The Japanese army required the soldiers to use condoms at the comfort station, but since many of them knew that I was new and probably didn’t have syphilis, they would not use a condom when they came to my room. Soon I became pregnant. When the proprietor found out that we weren’t taking the pills, he made everyone take them while he watched.

3