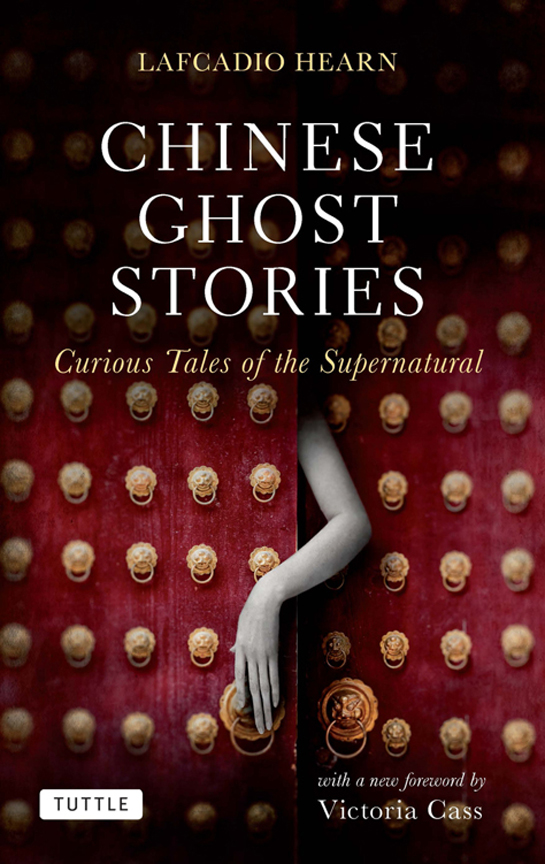

Chinese Ghost Stories

Read Chinese Ghost Stories Online

Authors: Lafcadio Hearn

Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

www.tuttlepublishing.com

Copyright © 2011 Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chinese ghost stories : curious tales of the supernatural / by Lafcadio Hearn ; foreword by Victoria Cass. – 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-1-4629-0016-9 (ebook)

1. Tales–China. 2. Supernatural--Folklore. 3. Ghost stories, Chinese. I. Title.

GR335.H39 2011

398.20951--dc22

2011002216

Distributed by

North America, Latin America & Europe

Tuttle Publishing

364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436 U.S.A.

Tel: 1 (802) 773-8930; Fax: 1 (802) 773-6993

Japan

Tuttle Publishing

Yaekari Building, 3rd Floor, 5-4-12 Osaki

Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141-0032

Tel: (81) 3 5437-0171; Fax: (81) 3 5437-0755

Asia Pacific

Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd.

61 Tai Seng Avenue #02-12,

Singapore 534167

Tel: (65) 6280-1330

Fax: (65) 6280-6290

15 14 13 1 2 11 1105MP

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in Singapore

TUTTLE PUBLISHING® is a registered trademark of Tuttle Publishing, a division of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

Contents

7 | |

8 | |

15 | |

22 | |

39 | |

49 | |

56 | |

68 | |

81 | |

86 |

To my friend

Henry Edward Krehbiel

THE MUSICIAN

WHO, SPEAKING THE SPEECH OF MELODY UNTO THE CHILDREN OF TIAN XIA—

UNTO THE WANDERING QING REN, WHOSE SKINS HAVE THE COLOR OF GOLD—

MOVED THEM TO MAKE STRANGE SOUND UPON THE SERPENT-BELLIED SAN XIAN;

PERSUADED THEM TO PLAY FOR ME UPON THE SHRIEKING YA XIAN;

PREVAILED ON THEM TO SING ME A SONG OF THEIR NATIVE LAND—

THE SONG OF MOLI HUA

THE SONG OF THE JASMINE-FLOWER

Preface

I

THINK that my best apology for the insignificant size of this volume is the very character of the material composing it. In preparing the legends I sought especially for weird beauty; and I could not forget this striking observation in Sir Walter Scott’s “Essay on Imitations of the Ancient Ballad”: “The supernatural, though appealing to certain powerful emotions very widely and deeply sown amongst the human race, is, nevertheless, a spring which is peculiarly apt to lose its elasticity by being too much pressed upon.”

Those desirous to familiarize themselves with Chinese literature as a whole have had the way made smooth for them by the labors of linguists like Julien, Pavie, Rémusat, De Rosny, Schlegel, Legge, Hervey-Saint-Denys, Williams, Biot, Giles, Wylie, Beal, and many other Sinologists. To such great explorers, indeed, the realm of Cathayan story belongs by right of discovery and conquest; yet the humbler traveler who follows wonderingly after them into the vast and mysterious pleasure-grounds of Chinese fancy may surely be permitted to cull a few of the marvelous flowers there growing—a self-luminous hua wang, a black lily, a phosphoric rose or two—as souvenirs of his curious voyage.

L. H.

NEW ORLEANS, MARCH 15, 1886.

Foreword

Where got I that truth?

Out of a medium’s mouth,

Out of nothing it came,

Out of the forest loam,

Out of dark night where lay

The crowns of Nineveh.

—Yeats: “Fragments,”

The Tower

, 1928

Lafcadio Hearn was a thief of myth. Born in 1850, into a time when the British Empire reached around the globe, he raided the world’s archives. Epic narratives, sacred recitals, ancestral prayers: all were fair game for his declared ambition: “I would give up anything to be a Literary Columbus.”

1

Hearn wanted to recalibrate the literary voices he knew, to create a “universal literature.”

Western storytelling had ossified, he claimed. “Naturalism”—with its solid portraiture of the minutiae of daily life—was narrow and dull. His “universal literature”

2

would be a hybrid of Western realism and “Eastern Literary growths.”

3

“Left to itself,” Hearn said, “every literature will exhaust its vitality if it is not refreshed by the contributions of a foreign one.”

4

It is unlikely that such a grandiose plan could have been anticipated for Hearn. Unprepossessing of figure, Hearn was, if not deformed, then disfigured; blind in one eye, he walked with a pronounced limp, both injuries suffered on the unforgiving playing fields of a Victorian childhood. Nor did the circumstances of his birth and childhood presage such learned ambitions. The operatic nature of his parentage, however, may have shaped his intelligence; his parents yoked the extremes of the British colonial landscape, and his childhood reads like a ballad.

His mother was a nineteenth century primitive. Rosa Antonia Kassimati was tribal, illiterate, beautiful and charismatic, born into a proud Cerigote clan on the Greek Ionian island of Cerigo. His father was Charles Bush Hearn, Anglo-Irish, a medical man from Dublin, with a chain of Protestant ministers in his lineage. He was dispatched as Surgeon on the British Army Medical Staff to Cerigo, where he met Rosa. The two fell in love and managed to carry on an affair. Learning of this injudicious insult to local mores, the men of Rosa’s clan attempted to murder Charles, but Rosa nursed him to health. They were married in a ceremony (one later held inconsequential by the Church of Ireland), and the romance continued. After two years in Greece she traveled to Dublin, to live midst her middle class in-laws. She lasted another two years, and returned alone, never to see her husband or sons again. From this cataclysmic mating of two nineteenth century polarities Patrick Lafcadio Hearn was born.

His life was worthy of fiction. He was a restless fantasist who lived his life in decades, moving across the globe like a figure on an antique game board. Born in Greece, taken then to Dublin, he then journeyed across the Atlantic to middle America where he stayed for eight years, then almost a decade in New Orleans: a short move eastward to the West Indies, and finally on to Meiji Japan, where he spent the last fourteen years of his life—a span of fifty-four years. He died in 1904.

After his youth in Dublin, Hearn began the life of a writer; but he began as any good protagonist does, by being cast from his family. In his last year of public school when he was eighteen, his family suffered a catastrophic financial reversal; and from this solidly middle class arrangement, he was dispatched to distant connections in the United States, with hardly a whisper of help from the adult realm. The Cullinan family—fellow Irishmen, now in America—gave him short shrift. Handing him a bit of money, they threw him out, forcing him to survive by his wits: “I was told to go to the devil, and take care of myself,” recalled Hearn; “I did both.”

5

Hearn then took, perforce, his first step as the “Literary Columbus;” he became—from Greece, via Dublin—at the age of nineteen, a journalist in Cincinnati.

The year was 1869, and the docks of this new American city were bursting with steamship trade, black citizens from the war ravaged South, and the high-minded rich engineering a trading hub. Hearn found his métier as a writer: becoming a literary omnivore, a prodigious author of anything publishable. He was a reporter, a poet, a fiction writer, folklorist, historian, travel writer, ethnomusicologist and essayist; and the borders marking the different forms were, for him, blurred. He was the Daniel Defoe of nineteenth century letters. Likewise, for this cacophonous imagination, no subject was too foreign, too local, too arcane or too low. Hearn spent eight years in Cincinnati, then ten years in New Orleans, and landed finally in Japan in 1890. He never stopped narrating. His accounts of markets, murders and show trials, fires and dissections, aberrant rituals and famous priests, folk practice and folk stories, local cooking, dialect and music—indeed local scenes and local worthies of every cast and character—are justly famous. “I have pledged myself to the worship of the Odd, the Queer, the Strange, the Exotic, the Monstrous.… Enormous and lurid facts are certainly worthy of more artistic study.”

6

He earned a living on these “Enormous” facts.