Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling (17 page)

Read Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling Online

Authors: Chris Crawford

This demonstrates your own ignorance, not their impenetrability. You’re on the science side of the Two Cultures divide, and you just don’t get the top thinkers on the other side of the chasm.

This demonstrates your own ignorance, not their impenetrability. You’re on the science side of the Two Cultures divide, and you just don’t get the top thinkers on the other side of the chasm.

Yes, there’s plenty of truth in that assertion. Whenever artsies start talking about semiotics, I feel like they must feel when confronting a mathematical formula. Yet there’s a difference, I think, between their grand theory and the grand theories of science. Even the most abstruse, exotic scientific theories ultimately relate back to the real world in some useful way. To put it in cruel terms, the physicist’s motto might well be “Give me a new theory, and I’ll make a weapon out of it!” We’re surrounded by a myriad of actual, working technological devices derived from abstruse scientific principles that the average person couldn’t comprehend—but that average person can still use the devices.

The geniuses of the artsy side of interactive storytelling don’t seem to have produced anything that could be boiled down to practice, however. I struggle through their works, trying to glean some useful bit of information that I can apply to my own work, and everything I read is obvious or irrelevant—or so it seems to me.

Aren’t you expecting too much? After all, Einstein never bothered to build a nuclear reactor, and Maxwell didn’t build any radios. Why should the top people on the artsy side have to worry about products?

Aren’t you expecting too much? After all, Einstein never bothered to build a nuclear reactor, and Maxwell didn’t build any radios. Why should the top people on the artsy side have to worry about products?

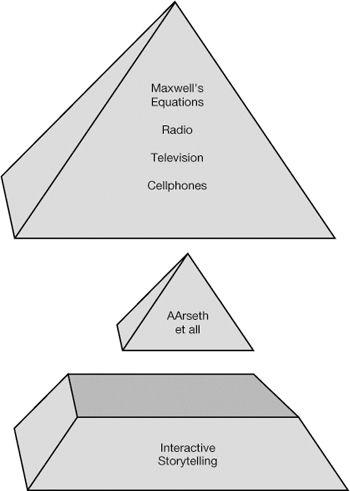

Einstein and Maxwell never worried about practicalities, but others used their theories to build products. The metaphorical pair of pyramids in

Figure 4.1

explains my idea.

FIGURE

4.1: Electromagnetic theory and interactive storytelling theory.

The physics pyramid has a base: all the ideas and products that flowed from Maxwell’s theories. The theorists of interactive storytelling, however, seem to be disconnected from the base of their pyramid. Nothing connects their work with the actual creating of interactive storytelling.

That’s not fair. The theory these people are working on is still in its early stages. More than a century separates Maxwell from cellphones. These people have had less than a decade. Give them some time!

That’s not fair. The theory these people are working on is still in its early stages. More than a century separates Maxwell from cellphones. These people have had less than a decade. Give them some time!

No, there’s still a difference. Maxwell’s theory wasn’t immediately

applied

, but it was immediately

applicable

. That is, any physicist of the time could see how to take existing technology and extend and improve it by using Maxwell’s theory. The time delay in applying Maxwell’s theory had more to do with the pace of technological development in the nineteenth century than the utility of the theory. The theory’s full ramifications weren’t immediately obvious, of course. That took further effort, but there was no question the theory fit into the rest of the sciences and would lead to new ideas and new technologies. Such is not the case with the artsies’ theories about interactive storytelling. I’m a practitioner

and

a theorist, and I can’t see how their work could be applied to anything other than more theory. This is what I mean by “bubble intellectualism.” It’s a complete, consistent, and impressive body of thought that has no connection with the rest of the intellectual universe.

I have to give artsies credit for trying to bridge the gap, at least socially. They have organized conferences on interactive entertainment and games, to which they always invite some representatives of the techie/games community. (It’s revealing that techies have never reciprocated, but merely acquiesced to an artsie initiative.) These conferences always start off with an earnest declaration of the need for academia and industry to work hand in hand. Then a techie gets up and talks about what he wants from academia: students trained in 3D artwork, programming, and animation. An artsie gets up and lectures about the semiotics of Mario Brothers. A techie follows with a lecture on production techniques in the games industry. Another artsie analyses the modalities of mimetics in text adventures. And so it goes, both sides happily talking right past each other, and neither side having the slightest interest in or comprehension of the other side’s work.

As always, you’re exaggerating the problem and neglecting the important exceptions. Carnegie-Mellon, MIT, and other universities have good cross-disciplinary programs, and the Europeans are taking the lead in educating artist-programmers.

As always, you’re exaggerating the problem and neglecting the important exceptions. Carnegie-Mellon, MIT, and other universities have good cross-disciplinary programs, and the Europeans are taking the lead in educating artist-programmers.

Yes, there are some good cross-disciplinary programs, but most are recognizable as either an arts program spiffed up with some programming and interactivity, or a computer science program spiffed up with some coursework on media. The projects students build always fall into one of two categories: a highly creative use of computer imagery and sound with nothing in the way of substantial programming, or a clever new algorithmic technique to do the same old stuff faster and with more colors or fewer polygons than anything done before. I have yet to see a single project at any of these schools that married creative use of imagery or sound with creative use of algorithms.

However, I’ll concede the point about Europe. The Two Cultures divide has never seriously affected continental Europeans; this problem seems to be a particularly American one. Perhaps European techies are inoculated against the Two Cultures virus by the experience of living in cities bursting with art. I suspect Europeans will eventually take the lead in interactive storytelling technology; perhaps then Americans will realize the seriousness of the problem and make serious efforts to catch up.

To some degree, the Two Cultures problem can be traced to events during the evolution of the human brain. As humans faced new challenges, various mental modules (refer back to

Chapter 1

, “Story”) developed to address those challenges. Two broad classes of mental modules developed: pattern-recognizing and sequential. The pattern-recognizing modules were finely tuned to process complex patterns, such as visual processing and social reasoning. Sequential thinking is used for auditory and language processing; it’s also important for the natural history module.

These two basic styles of thinking (pattern recognition and sequential) exist in every brain, but some minor genetic predispositions affect them. Gender specialization in hunter-gatherers (men did more of the hunting, women did more of the gathering) endowed men with slightly stronger skills in sequential thinking,

and the richer social environment of the base camp gave women a slight advantage in pattern-recognition. The cultural milieu in which children are raised magnify these small tendencies. The net effect is that men have traditionally dominated the sequential-thinking social functions, and women have played a larger role in the pattern-recognition social functions.

Guess what? There’s a bit of correlation between logic-versus-pattern and science-versus-art. It’s not an iron law, just a vague correlation. People who are stronger in sequential thinking gravitate toward the science and engineering side of the Two Cultures polarity. People who are stronger in the pattern-recognizing side are more comfortable in the arts and humanities end of the polarity. Therefore, the Two Cultures war is to some extent based on styles of thinking that stretch back millions of years.

What can you do to combat this sad state of affairs? First, fight intolerance. The next time somebody asks you how many artists it takes to screw in a light bulb, don’t go along with the joke; answer by calling the joker a pointy-headed nerd. That ought to put the joke in the proper light. If somebody makes a derisive comment about linear thinkers, tell ‘em you prefer linear thinking to intolerant thinking. Don’t let people get away with the crude behaviors that divide us from each other.

Second, take the time to really listen to people from the other side. It’s frustrating, I know, but it can be life-changing.

Let me tell you a story about a friend who changed my life. Veronique is all intuition and no logic. Because I worship at the altar of Reason, you might think that Vero and I were fated for mutual disdain, but when we first met, some sort of emotional connection transcended our differences. Perhaps it was the attraction of yin for yang; perhaps it was platonic romance. I don’t know. It certainly wasn’t a sexual attraction—I’m older and not up to the standards of this hot-blooded Frenchwoman. Whatever the attraction, we always enjoy our time together, talking endlessly about all manner of things.

One day we got into a discussion of reincarnation. Being a rationalist, I reject this notion as idle superstition. Vero thinks differently. So I decided to walk

her down the primrose path of logic, right into a trap. Step by step I led her toward my inexorable conclusion, making each step absolutely bulletproof. However, one step in my logical sequence was unavoidably soft. It wasn’t wrong, of course—I would never engage in deliberate mendacity. Although every other logical step was adamantine, however, this one wasn’t quite ironclad. I rushed through it and moved onto the next step. Vero listened politely as I went a couple of steps further, and then pounced on the vulnerable spot. With unerring accuracy, she stripped bare the flaw in my logic and demolished my argument. I was flabbergasted. How could she have seen the flaw? I interrogated her, trying to determine what logic had led to her discovery. There wasn’t any; she just knew.