Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling (20 page)

Read Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling Online

Authors: Chris Crawford

In interactive storytelling, plot is replaced with a web of possibilities that communicate the same message.

THE GREATEST OBSTACLE TO THE

advancement of interactive storytelling is the difficulty of

verb thinking

. This is an unconventional and almost unnatural style of thinking that is nevertheless central to understanding interactivity.

Verb thinking can be appreciated only in the context of its yin-yang relationship with

noun thinking

.

What is the universe? Most people answer this question by describing a collection of objects existing in a space. The universe is so many stars, galaxies, planets, and so forth. Our corner of the universe is composed of so many rocks, trees, animals, plants, houses, cars, and so on. To completely describe the universe, you need to list all the objects within it. Practically, it’s an impossibly huge task, but conceptually, it’s simple enough.

But there’s another way to think of the universe: You can think of it in terms of the processes that shape it, the dynamic forces at work. Instead of thinking in terms of objects embedded in space, you could just as well think in terms of events embedded in time.

These two ways of looking at the universe compose the yin and yang of reality. They show up in every field of thought. In linguistics, you can see this yin and yang in the two most fundamental components of all languages: nouns and verbs. Nouns specify things, and verbs describe events. Nouns are about existence; verbs about action. Together they make it possible to talk about anything under the sun.

In other fields, the yin/yang shows up in economics as goods and services. Goods are objects, things that exist. Services are actions, desirable processes. Goods are (mostly) permanent, and services are transitory. In physics, you talk about particles and waves. Particles are things; waves are transitory processes.

Military theorists worry about assets and operations. Assets are the troops, weapons, and ammunition that can be used in a war; operations are the military actions carried out with these assets. Together, assets and operations define military science.

Programmers see the dichotomy even more clearly: They have memory for storing data, and the CPU for processing data.

Data

is the “noun” of computers: It’s what is chewed up, sorted out, and worked over.

Processing

is the “verb” of computers, what does the chewing, sorting, and working over.

Even a factory manager unconsciously thinks in these terms. The factory starts with parts, the nouns of the operation, and applies labor, the verb of the operation, to build its products.

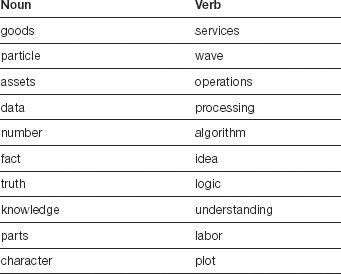

A simple table of terms that touch on this dichotomy demonstrates just how fundamental it is:

Because these two approaches of noun thinking and verb thinking constitute a dichotomy, we often think in terms of one side versus the other (nouns versus verbs, goods versus services, and so forth), but in fact the dichotomy is illusory; it’s really a polarity. A big gray zone where the two sides blend together shows up in every one of the human activities listed previously:

Language

: Nouns can be verbified (“

Trash

that memo!”), and verbs can be nounified (“That was a good

play

.”). In the process, the word’s definition can blur. Is “trash” intrinsically a noun or a verb? How about “play”?

Economics

: You purchase a hamburger at a fast-food restaurant. Are you purchasing goods (the burger itself) or services (the preparation of the burger)? When you hire a tax preparer, are you purchasing a good (the completed tax return) or a service (the efforts of the tax preparer)?

Physics

: The wave-particle duality drives everybody nuts. If you shoot electrons through a double slit, they’ll diffract, just like a wave. Yet you can detect each electron individually, just like a particle. So are electrons waves or particles? It depends. Massive objects behave more like particles. Tiny objects behave more like waves—but you can never isolate a single aspect of

the behavior. You can only make one aspect, particleness or waveness, very small compared to the other aspect.

Military science

: A small number of fast ships aggressively patrolling a sea zone can accomplish just as much as a large number of sluggish ships hanging around port. And obviously, a large army with plenty of assets can still accomplish a great deal if handled properly.

Computers

: From the earliest days of computers, programmers have realized that any computation can be carried out with almost any combination of data and process. If you can throw more memory at the problem, you require less processing and the program runs faster. If you’re short on memory, you can always rewrite the program to use more processing and less memory.

Factory

: The tradeoff between raw materials and labor consumption is well known. You can work “up the supply chain” by taking in more of the job yourself. Instead of purchasing finished printed circuit boards for your computer, you can purchase the parts and add employees to make the printed circuit boards. More labor means less parts.

Thus, the yin of nouns and the yang of verbs complement each other neatly; you can twist the dial one way to apply a “verbier” approach or the other way to get a “nounier” approach. Plenty of special circumstances, of course, cause you to lean more toward one side or the other. It’s a lot easier to think of Jupiter as a particle than to think of it as a wave with a very tiny wavelength. In your factory, if labor is cheap, you want to use fewer finished parts and more labor, but if labor is expensive, you want to use more finished parts.