Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling (24 page)

Read Chris Crawford on Interactive Storytelling Online

Authors: Chris Crawford

Now go over the artistic content of the snippet of pseudocode. It says that Darth has just two choices: WatchLukeDie or TurnAgainstTheEmperor. Yes, there could be a number of other choices: ProtestToEmperor, BegForLuke’sLife, LaughAtLuke’sSuffering, TurnAwayInSorrow, JumpBetweenLukeAndEmperor, or even PlayRummyWithAStormTrooper. Under other dramatic circumstances, these options might be appropriate for Darth, but this moment is the climax of the whole movie (indeed, the climax of the entire six-part series). You don’t want to spin this out into interesting sideways curlicues; it’s time for Darth to put up or shut up, so you give him a stark choice between two options. Remember, you could

give him more choices if, as a storybuilder, you wanted to play the storyworld out further; it’s a matter of artistic choice, not an absolute requirement.

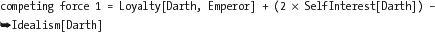

Having established the basic nature of the choice to be made, now turn to the criteria by which that choice is made. I have established that the force driving Darth to side with the Emperor is equal to his Loyalty to the Emperor plus hisSelfInterestminus hisIdealism. This is the simplest possible mathematical combination of those terms. However, I might want to place more emphasis on Darth’sSelfInterest, believing that it will play a larger role in the decision than his Loyalty to the Emperor. I can do this with a simple change:

All I’ve done here is doubled the influence of SelfInterest in the final outcome. I might also want to reduce the influence of Empathy in Darth’s decision:

competing force 2 = Love[Darth, Luke] + (Empathy[Darth] / 2)

Or I could make the influence of Empathy even smaller:

competing force 2 = Love[Darth, Luke] + (Empathy[Darth] / 4)

My point with these variations is to demonstrate how simple it is to express artistic ideas with arithmetic. There’s nothing absolute about these formulas; I don’t insist that dividing by 4 in the last formula is the only, or even the best, way to express it. You could have divided by 3 or 5 and still gotten decent results. The important idea is that I, as an artist, decided that Darth’s Empathy was a less important factor in his decision than his Love for Luke, so I scaled down the Empathy factor a notch or two.

To summarize, mathematics is just as valid a medium of artistic expression as oil and canvas, stage and actor, or pen and paper. The artist uses the medium to create metaphorical descriptions of the human condition. There’s one big difference: Mathematics, more than any other medium, addresses the

choices

that characters make. That’s because mathematics is about processes, not data. Other media can show the results of those choices, the attitudes of the characters, the anguish on their faces, but ultimately, the choice must be treated as a black box, like Darth Vader looking one way and then the other. Mathematics can delve

right down into the fundamental basis of the choice; no other medium can do that.

The notion that human traits can be represented by a mathematical variable raises my hackles. Human beings are infinitely complex creatures; reducing a person to a set of numbers is dehumanizing. The function of art is not to dehumanize people, but to explore and glorify the wonder of our existence.

The notion that human traits can be represented by a mathematical variable raises my hackles. Human beings are infinitely complex creatures; reducing a person to a set of numbers is dehumanizing. The function of art is not to dehumanize people, but to explore and glorify the wonder of our existence.

Here’s my counterargument: Remember, this is drama, not reality. Yes, real human beings are infinitely complex, but much of that complexity is stripped away in drama. Imagine the nastiest real person you’ve ever known; can that nastiness hold a candle to the Emperor’s nastiness? Have you ever known any real person remotely similar to Darth Vader? Anybody as dashing as Han Solo? The characters in movies are not real, complex persons; they are simplifications. A movie that’s 100 minutes long can’t delve into the infinite complexities of the human condition, so it discards most of that complexity to show a few glimpses of it in shining clarity. Thus, the mere fact that mathematical representation simplifies isn’t a significant argument against using mathematical expressions.

There’s still the argument that quantification is intrinsically demeaning.

There’s still the argument that quantification is intrinsically demeaning.

Is not loyalty a trait you can have more or less of? Are there not degrees of loyalty? If we can agree that loyalty does exist in varying degrees, what’s wrong with assigning numbers to those varying degrees? If we can say that Darth Vader’s loyalty to the Emperor is greater than Luke’s loyalty to the Emperor, is there any fundamental shift in thinking to assign numbers to reflect that?

But loyalty is a multidimensional concept, one that can’t be measured by a single number. There are differing kinds of loyalty: the loyalty to superiors and subordinates, the loyalty for family members, and the loyalty for friends. These different kinds of loyalty can’t be represented by a single number.

But loyalty is a multidimensional concept, one that can’t be measured by a single number. There are differing kinds of loyalty: the loyalty to superiors and subordinates, the loyalty for family members, and the loyalty for friends. These different kinds of loyalty can’t be represented by a single number.

Are these differences significant to the storyworld you intend to create? Will actors in that storyworld behave differently because they have these different dimensions of loyalty? If so, you must break down the single variable Loyalty into four separate flavors of loyalty, and quantify them separately. But if these differences aren’t significant to your storyworld’s artistic content, you can dispense with them and use the single factorLoyalty.

There’s a huge difference between talking about “greater” or “lesser” loyalty and “57”

There’s a huge difference between talking about “greater” or “lesser” loyalty and “57”Loyaltyor “23”Loyalty.

The verbal description leaves plenty of room for the approximate nature of appreciation of human qualities, and the quantitative description creates a wholly inappropriate impression of accuracy.

Consider the following list:

Greatest loyalty

Greater loyalty

Lesser loyalty