Circle of Stones (5 page)

Authors: Catherine Fisher

I jumped up, just as Forrest snapped, “Zac.”

I took the tray from her; she let go quickly, bobbed the speediest of curtseys & would have fled, but Lord Compton said, “So this is the young .  . . woman.”

He edged me aside with his cane & stared at her. “Very pretty.”

His gaze was appraising & bold. Not like you'd look at a lady. Sylvia held his eye a frightened instant, & the thought came to me like a flash of light from nowhere. She knows him.

Then she looked deliberately away from both of us to Forrest. “I'm sorry for interrupting, sir,” she said. “I didn't know .  . .”

“That's all right. Thank you, Sylvia.”

Her dress rustled as she turned; she caught at it as if to keep it quiet. Ralph Alleyn held the door for her. She might not be a lady, but he was certainly a gentleman. I cleared some papers & dumped the tray on the workbench, but when I looked up something had changed in the room, as if the girl had left more than her faint rose perfume behind in the air.

Then Greye said, “Well, I'll have to give this some thought.” He looked at Compton. “Are you coming, sir?”

His lordship was staring at the closed door, & I didn't like his face. Then he tapped his boot with the cane & looked up, hard, at Forrest. “I'll think about it too. Perhaps . . . there may be something here that interests me after all. Good day, gentlemen.”

“Show them out,” Forrest snapped at me. But they were already halfway down the corridor, so I shuffled past them & got to the front door & opened it.

The rattle of carriages sent a wave of dust into my face.

Greye lumbered down the steps, but his lordship stopped by me. He said quietly, “Forrest must be a difficult man to work for.”

My desire to punch him came right back.

He gave his cool smirk, took something out of his pocket & handed it to me. “Meet me tonight at ten. I have an offer to make you. I think it will interest an ambitious man.”

I took the card. That was my big mistake. I turned away. Then back. “What offer?” He just smiled. We stood face-to-face, & we were the same age, & the same height, & if my father had not gambled everything away, we would both have been wealthy young men. But he was richer than Satan & I was a madman's apprentice. He sauntered off down the street.

I shut the door & stood in the dark hall & read the card. It said:

GIBSON'S ASSEMBLY ROOMS

Pursuits & Refreshments for Gentlemen of Taste

Hot Bath Street, Aquae Sulis

I scraped my cheek with it thoughtfully. The very place Sylvia had fled from. Probably a gambling den. Hardly the place for Compton to offer me a job. Still, anything would be better than this madhouse.

In the workroom I could hear Forrest raging against his fate. “Ignorant, arrogant fools . . . surely we can do without their stinking money . . .” Fragments of his wrath came scorching out, but he had brought it all on himself, with his druid folly & his naive kindness. I leaned against the door & listened. Ralph Alleyn's soothing tones oozed through the opening.

“They will reconsider. Be calm, John. It will work out.”

I heard Forrest give a wheezy laugh. He was silent a while. Then he said, “I don't know what I'd do without you, old friend.”

“We will succeed. We have built our hospital, and soon we will make this a city where even the poor have fine homes. It's not a dream, John. You are making this happen.”

It was low & heartfelt. I turned away, uneasy.

Then I looked up. At the top of the stairs the girl was sitting on the highest step, watching me. “Don't eavesdrop, Master Peacock,” she said. “You might hear the truth about yourself.”

I shrugged. “So might you.”

She laughed, a saucy laugh. “I know it all. I just won't be telling it to you.”

As she stood I said, “You know the rich boy too. What are you really here for, Sylvia?”

She was still a minute. Then she walked into the drawing room & slammed the door.

Well. She might have taken Forrest in, but not me. She's no little innocent.

This might be getting interesting.

Bladud

I

can't tell you how long I lived by the water.

Its warmth was a wonder, as if the sun had sunk secretly into the ground. Although it was winter I lived in a small hollow of steamy heat, where summer plants bloomed in the soaked earth. Snow melted as soon as it fell.

I drank, I washed, I scrubbed at my raw skin.

The water became all I had lost. The warmth of humans.

The soothing of speech.

I felt it ripple in my hands, slither through my arms. Like something living. Like a girl.

And sometimes, in delirium or half asleep, I thought I saw her, the spirit of the spring, standing over me and watching me, clothed with green algae, her hair weed, her face sharp and laughing and full of secrets.

Slowly, over weeks, I unfolded.

I walked upright.

I ate the plants and beasts that haunted the place.

On a day of blue sky, I cleared the algae and lichens of the sacred spring, and I knelt down and bent over it and among the bubbles I saw my face.

For a long time I stared.

Tears ran warm down my clear skin and fell into the spring. There were no more scabs, no pustules, no oozing sores. I was cured, and I felt my strength gather even in the bones and nerves of my body.

And she was standing behind me, her shadow darkening the water.

I said, “What payment must I make to Sulis?”

Her answer bubbled from the depths of the world.

“Encircle my wildness. Hold me in a circle of stone.”

Sulis

S

he looked at herself in the mirror. The uniform was simpleâblack trousers, black sweatshirt with

Roman Baths Museum

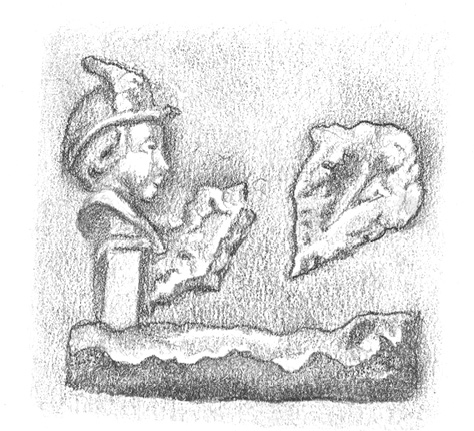

on it, and the famous image of the gorgon head that had been found here and that they used as their logo.

The clothes were featureless and she was glad. She wished there had been a cap, or something to pull down over her eyes, but that was silly.

As she stood in the cold staff cloakroom she wondered if all jobs were so easy to get. Was this how the world workedâyou knew someone who knew someone? The interview had taken less than ten minutes. The woman, Ruth, had looked stressed and in a hurry; she'd checked a few facts, name, age, the fake ID, and then said, “Right, well, the sooner you can start the better. Tomorrow?”

Sulis had said, “I'd rather Monday.”

“Fantastic. Seven thirty sharp please. I'll get someone to take you around.”

She had needed the weekend to reassure herself about the man. When she'd left the building on Friday the cafe table had been empty. She'd slipped into the crowd of tourists, and to be completely safe she'd taken a long, looping walk home, doubling back in the streets and ducking down alleyways and cobbled lanes.

Then she'd gone up to her room and out on to the secret ledge on the roof; crouched down and holding tight to the giant stone acorn, she'd kept a watch on the Circus for at least half an hour, intent on every stroller and vehicle, until Hannah had pulled up in the car below, and come up the stairs and called, “Su? Are you in?” and she'd found herself stiff and cold, one arm gone to sleep, her mind a strange blank.

No loitering man. Nothing unusual.

Nothing on Saturday.

Nothing on Sunday.

But she must have been too quiet, because Simon insisted they all go out on Sunday afternoon for what he called a family outing. It turned out to be a visit to a country house he was interested in, but she had enjoyed the vast green lawns and the woods with their falling leaves, and the cream tea in the cozy tearoom afterward.

Now, opening the door into the echoing hall of the museum, she told herself she'd imagined the man's interest in her. She had to get the old fear out of her mind, but it was hard. It lurked inside her, like a coldness in her chest, and though she could chat and laugh and seem normal, every time she was alone or the conversation flagged or a program on the TV stopped for the ads, there it was.

Like a shadow.

“Are you Sulis?”

It was the boy with the security badge. “I'm Josh. They've told me to give you the quick tour.”

He seemed a bit embarrassed by it all. “Fine,” she said, as coolly as she could. “Lead on.”

He wasn't a great guide. He went too fast and didn't explain things properly, as if he had other, more important things on his mind.

He led her down a corridor and outside onto a terrace of stone. “There it is,” he muttered.

She stared in amazement. Below her a vast rectangular pool of hot water steamed in the crisp autumn air. It seemed deep but it was hard to tell, because the water was the palest emerald green. Tiny trails of bubbles rose here and there to its surface.

She stared around at its paved edges, the classical columns, the statues. “Is all this Roman?”

“First daft question.” Josh leaned on the rail. “The bath is. The rest is later. This was the Romans' outdoor swimming pool.”

“Where does the water come from? How does it get so hot?” Suddenly she realized how little she really knew about any of this, despite the quick research in Sheffield.

“Deep underground. It gets hot down there. I don't know how. The earth's core is warm, isn't it?” Suddenly he straightened, posed like a lecturer, and adopted a voice of ridiculous poshness. “The King's Bath spring is a natural water source which rises from deep under the city. It flows at a rate of a third of a million gallons a day and has never been known to fail.”

She giggled. He said, “Quiet at the back please! The temperature of the water is a constant 120 degrees Fahrenheit. The water you are looking at is ancient. It fell as rain on the Mendip hills six thousand years ago and . . .”

“Is that true?”

“Well, it's what the guides tell the groups.” His voice trailed back to normal. He turned and walked on.

“Are you a guide?”

“No. But I want to be because the pay's better. And you get tips.”

“I don't think I could remember all that stuff.”

He shrugged but she could see he was pleased. “If you had to say it ten times a day you would. Down here.”

They were underground now. She trailed behind him through dark rooms full of exhibits, cases of Roman pottery and gravestones, altars, models and reconstructions, the broken life of the ancient bathers. Josh came back. “Bored, or bored?”

“I like it actually.”

“We're right under the square now. All those tourists and buskers and shops are about ten meters above us. Wait here a minute, will you?”

While she waited, she thought of the cafe tables, the man's dark eyes on hers through the crowd. For a moment she almost felt she was being watched again; she glanced around, but the museum was dim and shadowy, and there was no one here but her.

Something clicked, among the cases.

“Josh?”

There

was

someone watching her. She felt his eyes, the intent, secret scrutiny. Her hands were resting on one of the information panels; she was gripping it so tight her fingers hurt.

“Who's there?” she whispered.

Half-lit glass. Reflections of cups and Roman gemstones. A flat stone pavement, stretching into the dark.

Then she looked up, and saw the eyes.

They were stone, and they stared at her from a face, the strangely circular face of a frowning man with flowing mustaches and a corona of flames bursting out all around him. Or were they snakes? In the dimness it was hard to tell. But suddenly, as if Josh were switching everything on, spotlights erupted in a fused focus, and she saw that the face stared from the fragments of a broken pediment. And behind it, faintly, were two great wings.

For a moment something moved in her, deep in the shadows of her memory. She hugged herself. She wanted to cry out. Instead she whispered, her voice tiny in the underground chamber.

I know it's you. You told Caitlin she could fly. Why did you do that? She was my friend. You killed her.

Light.

A burst of music.

A voice rang out. “Welcome to the Roman Baths Museum. Our interactive displays are now open and we invite you to . . .”

“Sulis?” Josh had come around a corner and was staring at her curiously.

Normality clicked back with a jolt that seemed to jar right through her nerves; she breathed out smoothly and said, “I just dropped my watch. I don't think it's broken.” She pretended to fasten it, her fingers controlled now, the shaking gone.

For a moment he watched, as if he wasn't quite convinced. He said, “This place can give you the creeps in the dark.”

She turned. “Can it?”

Maybe her voice was cooler than she'd meant, because he looked almost hurt. Then he said, “Come on. We'll be opening in ten minutes.”

He showed her the rest of the rooms, but nothing really interested her until they came to the place where the water poured out from a great arched overflow, a roaring, steamy place that she could look at through a grille. She gripped the warm metal and pressed her forehead against it. “Look at all the coins!”

“People throw them in. Offerings.” He grinned. “At the end of the season we clean them out and split the profit between the staff. Mind, you get all sorts of junk. Foreign coins. Buttons. You'd think they'd show a goddess more respect.”

The heat was wonderful. A moist glow on her face and lips, like how she imagined a sauna must be. But they had to leave it, and as he led her back to the main hall he said, “Ruth said you were a student.”

Immediately she was on her guard. “I'm starting college in October.”

“Here?”

“Yes.”

“Most people move away.”

“We've only just moved here.”

He said, “From the North. I can tell by your accent.”

She made herself smile. “Is it that obvious?”

“Well, compared to the locals.” He was silent after that. As she followed him down the corridor she felt she had to be friendly back, so she said, “Are you a student?”

He didn't answer, and she couldn't see his face. Then he said, “No. Looking for a job.”

There was a warning note she recognized. It meant

Don't ask me about this,

and she knew exactly how that felt. When they reached the entrance hall he said, “Good luck,” and wandered off to open the doors to the public, and she went into the gift shop to start work.

It wasn't too difficult. By lunchtime she had gotten the hang of where everything was, the stationery, the tea towels, the expensive copies of Roman statues and jewelry. She couldn't operate the cash register yet, but Ruth said they'd teach her that soon enough, and could she just concentrate today on learning the stock, please, and the prices, and keeping it tidy, and watching the schoolkids who came through in great excited waves breaking over the sharpeners and pencils and tiny Roman soldiers.

At lunchtime she needed some fresh air, so she took her sandwiches out to Queen's Square, where there was a green space and some benches to sit on, and lots of people admiring the superb buildings. Simon had told her that this was Jonathan Forrest's first great masterpiece. “He did it before the Circus. Fabulous work.”

She sat in her coat and watched the leaves drift from the trees. Already she felt reasonably happy with the job; she liked seeing the tourists from all over the world puzzling over prices and trying to make themselves understood with phrases from guidebooks; she loved the mystery of the hot springs. For a moment she had a flicker of something that had worried her earlier . . . yes, that stone face. She glanced down at the logo on her sweatshirt. But she couldn't remember now why it had alarmed her, and she dismissed it and wondered if there would be time to go to Boots drugstore and get some moisturizer before she had to get back.

And then she saw him.

Every bone in her body seemed to petrify.

He was standing on the other side of the square, and he had his back to her, but she recognized the dark coat, so long it came below his knees. He was looking down at another one of the pigs dotted around the city, this one of transparent Plexiglass, so you almost didn't know it was there.

She stood, grabbing the bag that fell from her lap, shoving the half-eaten sandwich inside. The Coke can hit the ground and spilled.

He had not moved. But then she saw him reach out and touch the invisible pig, touch it lightly and run his finger over its surface. For a moment she almost felt the cold, slightly damp plastic. He raised his hand, held it up, its back to her, as if in greeting.

He must be able to see her. Reflected.

She turned and ran, pushing people out of the way, barging out of the gate and across the road, so heedless that a driver blared his horn at her angrily, and another braked hard. Ignoring the lights at the crossing she sprinted around a corner and into a shortcut she'd found, through the linked courtyards of an ancient almshouse, back out into a street lined with charity shops. She dived into the nearest, grabbed a skirt, gasped, “Can I try this on please?” and slid into the changing room, yanking the curtain across so hard it almost fell off.

Her heart was thudding. Breathless, she waited, her back against the mirror. After an anguished minute she opened the curtain a slit and peered out. There were a few people in the shop. The doorway was empty.

She didn't know what to do. Unless she phoned Hannah! As soon as the thought came she threw the musty skirt on the chair and dug out the mobile phone but stopped with it in her hand.

No. Stupid. She was panicking.

She imagined Hannah screeching up in the car and running inside, all scared, and the people in the shop . . . No. Take a breath.

Get a grip.

She sneaked another look out. The doorway was still empty. She sat on the wobbly stool and waited. There were ten minutes before she needed to be back at the museum, and she could make it in two from here.

There was a song on the radio. An old Bowie song. She let the music flow into her, concentrating on it, letting it take her somewhere else. Music always helped.

The curtain rattled. She jumped up.

“Have you finished in there, dear? Only there's someone else . . .”

“Yes. Sorry.” She opened the curtain cautiously. The elderly woman from the counter stood there with another elderly woman. They both looked at her, as if there was something strange about her. She made herself smile brightly. “Doesn't fit. Sorry.”

The skirt was hideous, she realized. As she put it back on the rack she almost laughed, and felt a cold shivery hysteria.