Circle of Stones (9 page)

Authors: Catherine Fisher

He glanced at Sylvia, then walked out. I heard him running down the wooden stairs & out into the street.

I closed my eyes. In the darkness in my head bright bands of pain flashed & stabbed like knives in a dungeon. I wanted to curl up & die.

After a while the girl's voice said, “Drink this.”

I refused to move.

“I said drink, Master Peacock. Or crawl outside & be sick. It's one or the other.”

I ungummed my eyes. She was holding a pewter tankard, & I was appalled. “Never. Never again.”

“It's not wine. It will do you good. We all used it at Gibson's.”

She was actually sitting on my bed. I forced myself to sit up. “I don't need your help.” It was so weak a lie I was not surprised at her laughter. So I snatched the beaker from her & drank.

“God!”

It was minutes before I could speak. “What utter bilge is that!”

Sylvia hugged her knees where she sat. “I won't tell you. You'd vomit.”

“Then don't.” I was shivering. I clutched the sheets about me.

“Finish it.”

She obviously thought I couldn't, so I did. It was totally, absolutely foul. Then I lay back & let the room swim in & out of my head.

“You went to see Compton.”

I didn't move. But her accusation came through the mist like a sudden stab of light.

“I could have told you not to go. He's filth, that one.”

I opened my eyes. She was watching me with that coy look I had begun to recognize. Her face was a little fuller, as if only a few days of good food had begun to change her. Some of the poxy spots had faded. I said, “How did you know?”

“You're not the only one who reads notes from other people's pockets.”

I sat bolt upright, the pain forgotten.

“Oh yes. I know all about how you spy on your master.” Her eyes were a scornful blaze. “What did Compton want? Has he got his claws in you?”

I had no intention of telling her anything. But I felt so sick I had to speak. “We played cards. I ended up owing him money.”

“How much?”

“More than I can ever pay. A hundred guineas.”

Her eyes widened. We shared a terrified moment, & then I managed a shrug. “Well, I must find the money.”

“Tell Forrest.”

“No!” My voice was sharp. “Never.”

She rose with a rustle of the silk dress & went to the window & opened it. Cold air gusted in, with a whistle of birdsong. I hastily curled in the bedclothes.

After a moment she said, “He ensnared you. Because he sees you & Forrest, how you are together. And he thinks, âThis one will get me what I want.' And what is that, Zac? What is it he wants?”

In the darkness of the blankets, I could not answer her. Instead I said, “Compton said I despised Forrest.”

She laughed. “So you do, Zac Peacock  .  . .”

“Stop calling me that!”

“Why? It's true.” She came & pulled the blanket off my face, & I saw she was pale with anger. “Take a good look at yourself. A wastrelâlazy & vain & sure the world owes him his fortune! Yet you

dare

to look down on Jonathan Forrest, a man worth ten of you.”

“I do not. I respect Forrest .  . .”

“Then show it.” She swept to the door & turned there. “You owe him everything just as I do. Why do you think he employs you? For your skill? You have none! Because your father pays him? Nothing is paid for you, Zac, not a farthing! Cook told me no one else in the city would take any apprentice for free, let alone pay him a wage. But Master Forrest takes in waifs & strays because he is a man of generosity & he knows what it is to be despised. A genius is never loved. Even when his desire is only to create beauty.” She gripped the door handle & took a breath. In a quieter voice she said, “Whatever it is Compton wants you to do, be careful. The fine lord is a gutter rat.”

“You'd know.”

I had managed to sit on the side of the bed. The room was still queasy, but I saw how she looked at me then, her glance as quick & fierce as a vixen's. We were both silent. For a moment I knew I could have spat back venom at her too, taunted her that she was Compton's creature, as much a traitor as I. I don't know why I said nothing.

She pushed back a wisp of hair. “Get up. Work begins today. We have to help him, Zac. The Circus is more than a building. It will be the perfection of his work.”

“What is his work to you? Who are you anyway? Is Sylvia even your real name?”

She and I eyed each other. Then she said, “If I tell you, you will despise me.”

“No.”

“I think so.”

“Try me.”

For a moment I thought she would. Then Mrs. Hall called & she cried, “Coming!” She turned & without looking at me said, “Maybe tomorrow.”

When she had gone I was left alone in the cold sunshine with my raging head. And her rose scent. And my rankling self-disgust.

Bladud

I

t is a strange thing to have been an outcast and now to be a king again. I looked at the land with new eyes. I saw its shapes and curves, that places in it were powerful and others were accursed.

As if the gods had left their footprints behind them.

I watched the people. They came from far away, beyond the horizon. They came on foot, carried on wagons, high on horses. They came with every sickness and disease, the blind, the foolish, the broken-limbed, the elf-stricken.

All of them sought the healing of Sulis.

For a time, I feared the spring would fail us. In hot weather I was sure it would dry up. But she never betrayed us. And so the people scrubbed themselves in the hot spring; they drank the sulfurous water.

They made statues of her, of branches and flowers, then of wood, then of stone.

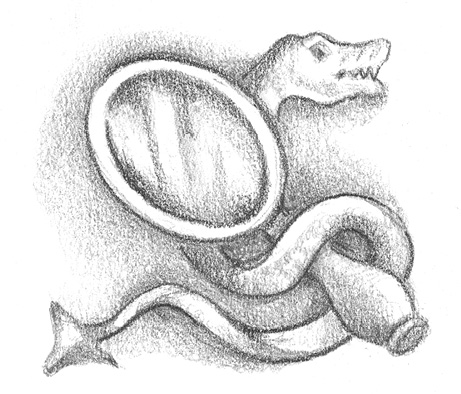

But I was not content. I had been touched by magic, and I had to pay her back. I wanted to inscribe my joy on the world. So I made circles. On the downs we made one that was vast and powerful, ring within ring within ring. I set an acorn in that ground too, that would one day be a great tree. And all around the spring, I built her a city, of fine houses, and a temple for her image, so that the bramble valley was a shining place. I lit a fire for her that would never go out.

Sulis

S

he was worried about Josh coming to the house and Hannah must have noticed, because after breakfast she said, “Everything okay?”

“Fine, thanks.”

“I've got a day off too. We could go shopping if you like.”

Sulis frowned. She was curled up on the window seat in the sunny sitting room flicking through one of Simon's books on the city. An illustration caught her eye; she turned the pages back to find it. “I can't. I mean, I'd like to, another day, but a friend's coming over. Any minute.”

“Anyone I know?”

“Josh. He works at the museum.” The questions were intrusive, but she tried not to get annoyed. Instead she found the page and smoothed it open. It showed a painting of three men in eighteenth-century coats and breeches gathered around a table; a stiff, formal group looking directly out at the viewer. Before them lay an artful scatter of pens, scrolls, surveying instruments, a model of the sun and moon. And a large unrolled plan of the Circus, overlaid with a triangle and some other strange symbols. One of the men had his forefinger touching the paper, pointing at the empty center of the Circus. Was he Jonathan Forrest?

A shadow on the page made her glance up. Hannah was turning a mug of tea in anxious hands; her hair was untidier than ever. She blew a wisp of it out of her eyes. “I don't want to pry, Su, you know that, but . . . well, when you say friend, do you mean like, a boyfriend?”

Sulis tried not to cringe. She kept her eyes on the page. “No, I don't. Just because he's a boy . . .”

“I know! Believe me, I hate asking. It's just . . . well, you know. The situation.”

Simon came in then. “What about the situation?”

“Sulis has made a new friend. Josh. He's coming over.”

The room was silent. Sulis realized her teeth were gritted with tension; she relaxed and glanced up at Simon. The whole thing was ridiculous. “If you want, I'll call it off. It's not that important . . .”

Simon had an armful of files and drawings. He put them down carefully on the table. “Maybe we need to discuss this a bit.”

“Why? You said live a normal life . . .”

“But you should have mentioned him, Sulis. I don't want to be heavy, but we have to be very careful.”

“He doesn't know anything about the past. He's my age. Do I have to tell you about everyone I ever talk to?”

She knew she sounded defensive; her voice had risen to a whiny, stupidly high note.

Simon sat down on the seat next to her. “Of course not.”

“Good.” To break the awkwardness she hefted the heavy book to face him. “Look. Is that Forrest?”

Simon glanced at Hannah. Then he took the book and looked at it and she sensed that he was being especially patient, his whole pose a considering caution. “Yes. That's him. I believe it's the only known image of what he looked like. You see he's pointing to the center of the Circus? There's a story that he wanted some sort of secret feature there, but whatever it was, was never completed. There was just a reservoir for water; you can see the roof of it out there, between the trees.”

She glanced out. The ground between the planes was thick with golden leaves. Simon followed her gaze. “Well, maybe not now. In summer. This man here in red was Ralph Alleyn, a local bigwig who owned the stone quarries. Pretty rich.”

“And him?” She pointed to the boy at Forrest's side.

“Zachariah Stoke. Forrest's assistant. Can't remember what happened to him. But look, Sulis, are you sure this Josh knows nothing about you?”

“He knows you're my parents. We live here. I'm going to college next year. That's it. End of story.”

She was used to lying, but she didn't like lying to them. They were so innocent somehow. As if she were older than them. Generations older. And in a way she was, because she had seen death and evil close up, and they never had.

Simon looked at Hannah. She said brightly, “Well, I'm sure it will be all right. Where are you going?”

“I don't know. It's up to him.” Sulis turned back to the book. She sensed Hannah's jerk of the head to Simon; they both went out into the kitchen and after a while the murmurs of their conversation drifted in.

Sulis stared hard at the painting, as if it could stop her hearing them. Zachariah Stoke looked about her age. He had a haughty, self-confident air, his head slightly on one side, as if he were listening to somebody too, in that distant room. Perhaps it had been a room in the Circus. Maybe even this one. He was handsome, and rather fine, but it was Forrest who interested her. The architect had a face full of energy, of fierce enthusiasm. He gazed out at her as if he challenged her; as if there was something she and he could share. Perhaps, she thought, it was that each of them had only one image that the world could see. One picture that would define them forever. “So this is how they caught you,” she whispered. There was a sadness about him too, as if all the things he loved had failed him.

The doorbell rang.

Sulis looked up. She felt a sudden pang of nerves, and that annoyed her. Josh was early.

“I'll go.” Hannah came out of the kitchen. “Are you okay about him coming up?”

“He'll have to. I'm not ready.” She put the book down and hurried upstairs.

As she found her coat and money, she heard voices below; when she ran down Josh was standing by the window talking to Simon politely about the view.

“It's a bit like a clock,” Josh was saying. “A stone clock.”

“Well, yes. The sun travels around it. The shadows of the trees are like dark pointers.” Simon sounded impressed. “Are you a student?”

“I was. Not now.” That tense note had come into Josh's voice.

“Architecture?”

“Archaeology.”

“Really? Well, if you're interested, there's a project about to begin here in the Circus that you might help me out with. I can't promise money . . .”

Sulis said, “You never told me that.” Simon turned. “Oh well, I was going to, of course. It's not exactly glamorous. A new storm drain is due to be laid across the green down thereâit will run from roughly our cellar to the other side, so I've pulled a few strings and the contractors have offered the university the chance to work there if anything turns up.”

Josh said, “What sort of things?”

“Who knows?” Simon smiled his lecturer's smile. “If you're interested . . .”

Sulis was annoyed. “I'm interested.”

“Oh, I meant both of you, of course.”

Hannah was clearing the breakfast table. “Just like a man.”

Sulis moved to the door. She had to get Josh out of here. “I need to get my phone.” She pulled his sleeve. “Come on. I'll show you the view from the roof.”

In her bedroom she opened the window and he stepped through and whistled. “This is amazing. Have you ever worked your way along the roof?”

“No. And don't you.”

He put his arms around the stone acorn. “These things look smaller from below. Why acorns, anyway?”

“Bladud's crown, so Simon says.” She grinned.

“Simon says.”

Josh even laughed. He seemed different today, up here. Less self-absorbed. Happier. Above him the sky was blue and clear and cold. It was as if they had risen above their lives and, for a moment, were free.

A voice echoed, strangely distorted. It spoke garbled, harsh syllables.

A ripple,

it said,

in the pool of time

.

“What's that?” Josh turned.

She sighed. “The tourist bus.”

It came around the corner, as it did every hour, the red double-decker slowly purring along the circular road.

“Do they look in through your windows?” Josh grinned.

“Sometimes.”

The commentary drifted across to them, the woman with the microphone in hat and scarf, her voice rebounding from the opposite houses.

“. . . Jonathan Forrest's masterpiece, built to a complex and secret theory. Thirty houses in three sections, using the three orders of architecture. Begun in 1740, Forrest's survey of Stonehenge inspired his . . .”

The bus came around toward them, scattering jackdaws into the trees. There were a few people downstairs, all foreign tourists, but on the upper, open deck, there was only one man. He was sitting on the backseat, muffled against the cold in a coat and a scarf wrapped tightly around his neck. Sulis stared at him.

Was it?

Dread paralyzed her. Josh was talking, but she couldn't even hear him.

The man had dark hair. He was gazing at the houses he passed intently, with a fixed fascination, and yet he was doing something too, dialing a number into a mobile phone he held.

“Sulis?”

Josh had had to stand directly in front of her. “Am I that boring?”

“It's him.” She pushed him aside, and he wobbled and grabbed hastily at the acorn.

“Be careful!”

“It's him. I know it. There,

look

!” She grabbed him, turned him. “At the back, on his own.”

He stared. The bus drew slowly level with them. The man raised his eyes and gazed calmly across at them.

“. . . please note the mysterious frieze of images above the columns,” the microphone droned. “Symbols of occult and unknown imagery, as if Forrest was leaving a message for later generations, never deciphered . . .”

The man smiled at her.

Sulis couldn't move. She stared at him and he gazed back, and she was on the top of the tower in her red coat and Caitlin was standing too near the edge, sidling toward it one foot at a time saying, “It's okay. It's quite safe, look.” But then Caitlin was a boy and he was saying, “Are you sure it's the same man? I don't think it is.”

“Sure. Utterly sure. I dream about him.”

The man lifted the mobile phone to his ear. He leaned back on the seat, gazing at her.

Her phone rang

.

The shock was so great she dropped it. It fell with a clatter onto the narrow stone ledge and skittered to the edge. The vibrations of its ringtone made it shudder in a tiny circle.

Josh crouched. “I can get it.”

“No! Don't!”

“I can reach it.” His fingers groped. “It's just . . .”

He leaned farther.

“Don't!”

“It's okay. It's safe. Look.”

She stood behind him and the wind blew and the birds cawed and flew around her. The man's eyes were fixed on her and she was sick and shivering and she had hold of his coat and was pulling and she wanted to scream but the words were choked in her throat.

Josh's fingers closed on the phone. He scrabbled it nearer. “If I can just . . .” He was over the empty, sheer edge of the roof.

“Caitlin,” she breathed. “Don't . . .”

He squirmed back. He scrambled up. “Who's Caitlin?”

“She's dead,” she whispered.

Awkward, he handed her the phone. “You should answer this.”

“No. No one knows this number. No one but Hannah and Simon.”

He held it out to her, but she couldn't take it. The bus had passed them; it was turning out of the Circus and through the windshield at the back she could still see the man sitting there. He didn't turn his head.

“Hello?” Josh had the phone to his ear, looking at her. “Who is this?”

She knew who it was

.

Intent, she watched Josh's face as the jackdaws came down in a squawking cloud on the roofs and the trees.

For a minute he was expressionless. Then he pushed the button and gave the phone back to her. “No answer.”

She looked at the tiny screen. It said NUMBER UNAVAILABLE. She felt giddy. For an instant she felt how the whole world was spinning around the sun, in a circle so fast no one even noticed. She took a step sideways and bumped against the acorn. The sun was blinding her eyes.

She didn't remember how they got inside. She was sitting on the bed and Josh was propped on the chair. He was looking at her.

They were both silent.

For a moment there was only silence, and then he said, “We should go out.”

“No! We'll stay here.” She swallowed. “I'll tell you here.”

There was no sound from below. Simon would have gone to work and if Hannah had shouted up to say she was going out, neither of them would have heard her. The small room was quiet and warm and the sunlight streamed in.

Josh took his coat off and tossed it down. “I could murder a cup of tea.”

She had to talk. She said, “That photo. On the book cover.”

She leaned over and pulled a drawer open and tossed the book onto the bed. They both stared at it. Josh didn't touch it. He said, “This Caitlin . . .”

“She's in it too.”

He leaned back. He took a small wooden clown that was on her table and pulled the string that made it collapse. But he didn't say anything.

And suddenly the silence yawned, and she knew only her words could fill it.