Citizen Emperor (112 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

At Lyons, Napoleon, perhaps sensing the anti-royalist and pro-Jacobin sentiments among the crowds that welcomed him, began to dismantle the Bourbon monarchy by reinstating the tricolour flag, by extending an amnesty to military and civilian officers who had worked for the Bourbons (with some exceptions, such as Talleyrand), by confiscating property belonging to the princes of the House of Bourbon, by dismissing officers who had been integrated into the army since their return, and by expelling émigrés who had returned to France since 1 January 1814; in addition, émigré lands that had been restored were now to return to the state, the Chamber of Peers and the Chamber of Deputies were dissolved, and a decree calling for the representatives of the nation to come to Paris (in May) was issued.

15

At Lyons, it looked as though the spirit of 1789 and indeed 1793 was alive and well. The populist, radical reaction took a lot of people by surprise, including Napoleon, who then went about using it to his political advantage. Once in Paris, he issued a number of decrees that were supposed to cement his revolutionary credentials: all ‘feudal titles’ were suppressed (in fact they no longer existed); the nobility was abolished (it had been done away with in 1791); and all those who had accepted ministerial office under the Bourbons were to be exiled from Paris. Almost a thousand people would be arrested and arbitrarily detained and nearly 3,000 were placed under house arrest.

16

Historians have described these actions of Napoleon as combining the liberal notions of the Revolution, which essentially set out to establish a constitutional monarchy, with the more radical phase of the Revolution of 1793, encapsulated by the Terror, anti-royalism and anti-clericalism.

17

This is true, but it is an oversimplification. As a child of the Revolution but also as a man wanting to reassert his imperial authority, Napoleon had little choice but to undo the foundations of the returned Bourbon monarchy, and at the same time to promise a more liberal national assembly. Was this going against the grain,

18

or was Napoleon being his most practical, opportunist self ? He certainly played to the crowds when he thought it necessary. At Autun, for example, he was heard to talk about hanging priests and nobles from a lantern (

lanterner

).

19

This found an echo with the silk weavers of Lyons, who chanted, ‘Down with the priests! Death to royalists!’

20

Napoleon caught on very quickly. He suddenly rediscovered his revolutionary roots, carried away by his own enthusiasm, imitating what he heard around him, pitting the poor against the rich, the peasantry against the local parish priests. He was now a man of the people, democratic, anti-Bourbon.

21

Neo-Jacobins at least liked what they heard; they rallied to him as the legitimate heir of the values of 1789. In the months that followed, anti-Bourbon sentiment was tapped into as Napoleon’s new regime churned out caricatures that mocked Louis XVIII’s physical appearance and reminded onlookers of the role the allies had played in restoring the Bourbons to the throne.

22

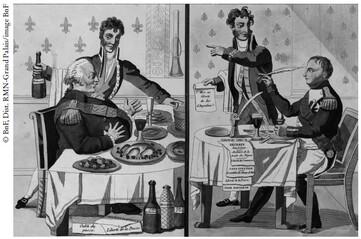

Anonymous,

Glorieux règne de 19 ans – Comme il gouverne depuis 15 ans

(The glorious reign of nineteen years – How he has been governing for fifteen years), 1815. In the image on the left we see a corpulent Louis XVIII, who had theoretically reigned since the death of the dauphin in 1795, sitting at a horseshoe table full of food and drink, his responsibilities under his feet marked ‘the Charter’, ‘forgetting the past’ and ‘freedom of the press’, among other things. To the right is Napoleon, working at a table with little food and drink, with a pile of papers whose labels include ‘freedom of religion’ and ‘the abolition of slavery’. He is signing a document releasing from prison the Duc d’Angouleme, the Comte d’Artois’ son.

The revolutionary rhetoric was in complete contrast to the moderate image Napoleon was also cultivating. If it did not inflame old hatreds against priests and nobles, the rhetoric opened old wounds that allowed those who had felt oppressed under the Bourbons to vent their frustration and rage. This was especially the case in the provinces where priests and nobles were harassed and sometimes attacked. The revolutionary song, ‘La Marseillaise’, also revived old animosities. Napoleon had always been very wary of ‘La Marseillaise’; it was almost never sung during the Empire, and was deleted from the official list of songs.

23

The troops who rallied to him, however, began to sing it again in the weeks and months leading up to Waterloo.

24

Napoleon, nevertheless, refused to rely on the people, especially those of Paris, whom he associated with the worst excesses of the Revolution and referred to as the ‘dregs of the populace’.

25

His new regime had to be built on more solid foundations if he were to succeed in rallying the notables.

What followed has become part of the Napoleonic legend. It took Napoleon nineteen days to journey from the south coast of France to Paris, avoiding those towns and regions where he knew he was likely to get a less than warm welcome. The itinerary had in fact been planned in great detail by two obscure supporters of the Emperor: a glove-maker from Grenoble, Jean-Baptiste Dumoulin, and Napoleon’s military surgeon on Elba, Joseph Emery.

26

We cannot say with certainty that France welcomed Napoleon’s return. Certainly, before he landed at Golfe Juan, there had been growing anxiety about the Bourbons and their more extreme supporters, who managed to destroy very quickly what goodwill had existed between the people and the Bourbons.

27

None of this of course explains the rapid collapse of the Restoration government when faced with the landing of Napoleon and a few troops. The reaction of the army was crucial. Just as it had been necessary to Bonaparte in 1799, so too was the army’s role fundamental in allowing Napoleon to regain power in 1815.

28

This time, however, it was not so much the superior officers as the subalterns and the rank and file who were decisive. Despite the Restoration paying the army more attention in the first couple of weeks of March than it had done the whole of the previous year, and despite a campaign in the press to rally the army to the Bourbons, the common soldier turned his back on the king and went over to Napoleon.

29

Attempts on the part of high-ranking officers to garner support for Louis with cries of ‘Vive le Roi!’ were met with stony silence.

30

The ‘contagious mutiny’ that took place from below was made possible, however, only because the common soldier was pushed along by the people.

31

In Vienna, things had not been going well. This is not the place to go into the difficulties the allies faced in coming to some sort of post-Napoleonic settlement, but the situation had deteriorated to such an extent over the Polish and Saxon questions that war appeared inevitable. It got to the point where Alexander was reported to have threatened to ‘unleash’ Napoleon on them.

32

One of Francis I’s chamberlains, the Count von Seilern, had the same idea.

33

Frederick William and his generals were so unhappy with the way things were progressing that they talked openly of war.

34

Their inability to obtain the whole of Saxony did not go down at all well in Berlin. The Prussian Chancellor’s house in Berlin was attacked by a mob, although nothing more than a few windows were broken.

35

The Prussians it would appear were spoiling for a fight, and not necessarily against France. Many believed it would inevitably come to that at some time in the future. Two days before Napoleon’s return, Louis XVIII wrote to Talleyrand with instructions about what to do in the event of war.

36

And then, on the morning of 7 March, news of the landing of the ‘monster’ in the south of France arrived. Though the remarks of the Polish Countess Potocka about sovereigns and ministers sleeping with their hats on and their swords by their sides can be taken with a grain of salt, the initial reaction was nevertheless one of stupefaction mixed with fear.

37

The King of Bavaria ‘lost his appetite’, Alexander was alarmed and even Metternich was unable to maintain his composure.

38

Frederick William insisted Napoleon should have been treated more harshly.

39

When Marie-Louise heard the news, she remained entirely composed in public, but then burst out crying when she retired to her apartments.

40

The only person not to have been affected appears to have been Talleyrand, who remarked, ‘It is a masterstroke.’

41

Later he declared, ‘That man is organically mad.’

42

Talleyrand was not the only person to use that expression. Caulaincourt described the ‘enterprise of the emperor’ as ‘mad’.

43

Not everyone, however, was displeased by the news. Some of the minor German princes, but especially the Prussian military, were delighted. The German princes saw it as a chance to reopen negotiations, while Prussia saw it as an opportunity to regain more territory in the inevitable war.

44

The allies were hoping, in vain, that the French would rally round their king. On the same day that Napoleon was dismantling the Bourbon regime from Lyons, 13 March, the allies issued a declaration in Vienna stating that Napoleon had placed himself beyond the ‘pale of civil and social relations’ and that the French people would consequently ‘annihilate this last attempt of a criminal and impotent delirium’.

45

They argued, hypocritically under the circumstances since they had been contemplating his forced removal from Elba, that as Napoleon had broken the Treaty of Fontainebleau he had ‘destroyed the sole legal title by which his existence was bound’. The objective was clear – the allies declared war not against France or the French people, but against Napoleon. It was a well-worn tactic that had been used during the campaigns of 1813 and 1814, and as far back as 1804, when the Russians declared that they were waging war not on the people of France, but on its government, ‘as tyrannic for France as for the rest of Europe’.

46

In that way, the coalition would appear to be anti-Napoleonic rather than anti-French.

It was also a call for assassination. Most of the other allied representatives baulked at assassination, but they did agree that Napoleon had placed himself outside the law, which essentially meant that he could be treated as a mad beast and shot on sight by any peasant who wanted to take a crack at him.

47

The idea of killing Napoleon had been around for a long time and had been contemplated by at least some of the allies. During the campaign for Germany in 1813 Bernadotte had declared, ‘Bonaparte is a scoundrel. He has to be killed.’

48

In Paris, Louise Cochelet, reader to Hortense de Beauharnais, reported that many royalists were glad that Napoleon had had the idea of leaving his island, and that he would be ‘hunted down like a wild beast’.

49

In England, on the other hand, radical writers and thinkers were outraged. An article by William Godwin appeared in the

Morning Chronicle

dubbing the appeal for assassination counter-productive and ludicrous.

50

More practically, there were some in the allied military camp who thought Napoleon should be captured and shot. The Prussian general, Gneisenau, was one.

51