Citizen Emperor (46 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

‘Peace is an Empty Word’

One year after the foundation of the Empire, Charles de Rémusat, a former noble who had rallied to Bonaparte, believed that its success was not yet assured.

164

The news of the battle of Austerlitz did not change that, but it undoubtedly lent a certain splendour or éclat to Napoleon’s reign. The brilliant military campaign consolidated his position and reinforced the aura of invincibility that he had been cultivating since the first Italian campaign.

In many respects, Austerlitz completed the transformation of Bonaparte into Napoleon. Before that, contemporaries could be forgiven for thinking that he was just another competent French general, if somewhat better than most. There was nothing particularly novel about his campaigns in either Italy or Egypt that could have led contemporary military observers to think that they were dealing with a genius on the field. The Italian campaign of 1796–7 was marked by the rapidity of his successes, as well as their political exploitation, but there was no one battle as decisive as the knockout blow that was Austerlitz. The Egyptian campaign had very mixed results, but was easily exploited by Bonaparte in an aura-building exercise. The battle of Marengo, as we know, he almost lost. Moreover, the campaign was only won six months later with the victory of Moreau at Hohenlinden. Austerlitz was different; it was the first decisive battle – the war was effectively over in three months – a feat that was to be successfully repeated at Jena-Auerstädt and Friedland.

165

But it also changed the way in which Napoleon approached campaigning. He believed he had developed a new approach and that he could repeat the performance each time he went to war.

166

Part of the reason for this was that the characteristics of Napoleonic warfare – the speed with which marches were carried out, the mutual support derived from corps formations, and the maintenance of large reserves in the rear ready for the decisive blow – were not yet so readily documented or discussed as to have become generally recognized.

167

Austerlitz is often seen too as a watershed in the development of Napoleon’s character. We do not know what he thought about his victory or what may have gone through his mind when he defeated Francis and Alexander, but it must have had an impact on him. From that time he is supposed to have assumed an increasingly imperious tone. This, however, is based on the mistaken assumption that he was something other than imperious from the start. There is enough evidence to suggest that since the first campaign in Italy he had been growing in arrogance and conceit. Take, for example, his aside to Cambacérès in August 1805, months before Austerlitz. After dictating a letter to Talleyrand ordering him to inform French envoys throughout Europe that he was being forced to go to war with Austria, Napoleon turned to his arch-chancellor and remarked, ‘Anyone would have to be totally mad to make war against me.’

168

In October, in a memorandum written from Strasbourg, Talleyrand had argued that France would be much better off with Austria as its ally rather than its inveterate enemy. He recommended a ‘lenient peace’ with Austria, one that would even lead to an Austro-French defensive alliance.

169

This could be done, he argued, by setting up what today would be called buffer states between Austria and France in Germany. It was an intelligent enough approach, although scholars have pointed to its flaws, namely, that it excluded Austria from any direct control in Italy and Germany and thus set the foundations for future conflict.

170

Napoleon appears to have been persuaded by his foreign minister’s arguments – until after Austerlitz, when his attitude hardened overnight. In victory, he became less generous. He imposed a demanding treaty on Austria not so much as a result of the victory, but because Austria quickly became isolated on the diplomatic scene, after being abandoned by both Prussia and Russia. What he was now looking for was not peace – a word he thought empty

171

– but rather a ‘glorious peace’; any negotiation had to be conducted from a position of strength.

It was. On 26 December, Austria signed the Treaty of Pressburg, incurring a considerable number of territorial losses: Venice, Dalmatia and Istria were ceded to the Kingdom of Italy; Brixen, Trent, Vorarlberg and the Tyrol were ceded to Bavaria.

172

In addition, Vienna was saddled with a war indemnity of forty million francs. It was in part a result of Napoleon’s belief that Austria was his main Continental enemy – a belief engendered by his experiences in Italy during the first and second Italian campaigns: he was therefore trying to hobble the country so that it could no longer do any harm.

173

Although it makes no sense from either a foreign-political or even a personal perspective, Napoleon felt he had been duped by Austria. If it had appeared willing to negotiate with him before the outbreak of war, that was (in his mind) a ruse allowing it time to mobilize for battle.

174

This is possible, but another explanation can be offered. The defeat of Austria and Russia presented Napoleon with an opportunity that had not existed before the battle. He was now in a position to reshape all of southern, northern and central Europe, to transform the Grand Nation into the Grand Empire.

175

Over the next few months, he installed Joseph as King of Naples, and Louis as King of Holland (Eugène, it will be recalled, had already been installed as viceroy of Italy). In Germany, the Holy Roman Empire was abolished and replaced by a Confederation of the Rhine under French influence. The Electors of Bavaria and Württemberg were made kings, while Charles, Duke of Baden had his duchy transformed into a Grand Duchy. As with previous treaties hammered out by Napoleon, such as Leoben, Lunéville and Amiens, the seeds of further unrest were very much present. Francis always hated the peace that had been imposed on him at Pressburg, and he began to look around for allies to undo it almost immediately the guns had fallen silent. And as with other treaties signed by Napoleon, he reneged on them within months.

11

Napoleon the Great, Napoleon the Saint

Napoleon returned to Paris in the first flush of victory on the evening of 26 January 1806. In the weeks and months following the battle of Austerlitz, one can discern an attempt not only to exploit the victory to the fullest, but also to establish a cult centred on Napoleon. In an issue of the

Moniteur

in 1806, the minister of the interior Chaptal published an ‘Ode sur les victoires de Napoléon le Grand’ (Ode to the victories of Napoleon the Great), in which a Frenchman wakes up Homer to ask him to come back to sing the glory of a hero who by his actions had effaced the names of the great heroes of antiquity.

1

References to Napoleon as ‘Great’ were in evidence even before the coronation in December 1804, but they were uttered in private.

2

Now there was public acknowledgement of the epithet as the Senate passed a vote to construct a monument to ‘Napoleon the Great’.

Propaganda was not a word employed by contemporaries. Instead, people spoke of the ‘management of opinion’ (

direction de l’opinion

).

3

That is why Napoleon insisted on having men who were ‘attached’ to him at the head of the newspapers, and who had the ‘good sense’ not to publish material that was damaging to the nation.

4

There was a punitive as well as a constructive tradition involved in cultivating his image. The punitive tradition was common to eighteenth-century absolutist states and involved removing those who tarnished Napoleon’s image. Journalists and newspapers were censored or closed down, and in extreme circumstances journalists were executed.

The constructive tradition involved grafting Napoleon’s image on to existing popular culture.

5

To this end the Emperor tolerated and even encouraged traditions, such as religious festivals and other public celebrations, that dated back to the pre-revolutionary era, and that he could use to promote his image. Thus the Festival of the Federation on the anniversary of 14 July was first relegated to a public holiday in 1803 and 1804, and was no longer celebrated at all after 1805. Instead, Napoleon created his own festivals with a military aura. The translation of the remains of Marshal Henri de La Tour d’Auvergne, Vicomte de Turenne, to the Invalides in 1801, the construction of triumphal arches, the Distribution of the Eagles, the celebration of victories, and the translation of Frederick the Great’s sword to the Invalides in 1807 fall into that pattern. The army often took centre stage in Napoleonic festivities to create a ‘culture of war’ that united citizens and conscripts around the flag.

6

The most Napoleonic of festivals was the creation of the anniversary of St Napoleon. But the regime went even further by attempting to instil a degree of sacrality that had not been seen since before the Revolution: an imperial catechism was introduced that made a direct link between God and Napoleon; and 15 August, which happened to coincide with both the Assumption and Napoleon’s birthday, was declared a national holiday to celebrate the founding of a new saint – St Napoleon.

In the Catholic calendar, 15 August was the Feast of the Assumption. Under the Empire, however, the Virgin Mary was conveniently forgotten and effectively replaced by a St Napoleon invented to fit the regime’s agenda. Napoleon’s birthday became a sort of ‘personal canonization by decree’.

7

A number of dates were toyed with, including Easter and Corpus Christi, both of which were rejected by Napoleon; even he was not so conceited as to want to associate himself directly with Christ.

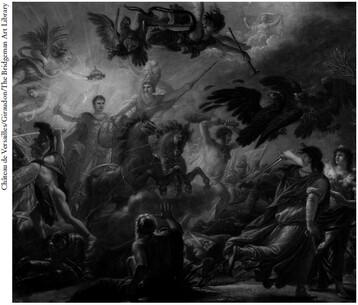

Antoine-Francois Callet,

Allégorie à la victoire d’Austerlitz, 2 décembre 1805

(Allegory of the victory of Austerlitz, 2 December 1805), 1806. A series of twelve paintings was commissioned to decorate the gallery of the Diane Palace at the Tuileries. One of the most interesting is this allegorical painting by Callet in which Napoleon is represented as the god Mars driving before him the two imperial eagles of Russia and Austria.

It was (and is) customary in France to celebrate the feast day of one’s namesake, but Napoleon’s feast day became a pretext to celebrate the birth of Napoleon,

8

almost as though it would have been improper simply to declare his birthday a national day of celebration.

9

Nevertheless, the introduction of a new saint and a new feast day did not occur overnight. The Feast of St Napoleon was first mentioned in the

Almanach national de la France

(National almanac) in 1802, details of which were published the following year.

10

In the literature of the day, Bonaparte was referred to as the

Pacificateur des Nations

(Peacemaker of nations) and as the

Régénérateur de la France

(Regenerator of France), as the person around whom everyone could rally, the person able to stifle discord, themes that had been touted even before his ascension to power in 1799.

11

The festivities celebrating his nomination as Consul for life were held on 15 August.

12

The feast day was mentioned again at the camp of Boulogne when Napoleon was handing out Legions of Honour (16 August 1804). In 1805, the canons of Nice asked Napoleon for permission to dedicate an altar to a (non-existent) St Napoleon.

13

All of this seems to have been designed to prepare public opinion leading up to the first official celebration of the feast day in 1806.