Citizen Emperor (66 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

Napoleon did not reserve his violence for his servants; high-ranking men came in for thrashings too. The Comte de Volney, a writer and member of the Senate, was kicked in the stomach during a ‘discussion’ about the Concordat in 1802. Napoleon then rang for someone to come and pick him up and coldly ordered him to his carriage.

123

Volney sent in his resignation as senator the next day, though Bonaparte did not accept it. Napoleon once hit the minister of the interior, Chaptal, with a roll of papers, like a master hitting his dog; and he is said to have pushed the minister of justice (Régnier, not Molé) on to a sofa and laid into him with his fists. During the campaign in Germany in 1813 he struck a general across the face. Diplomats too came in for verbal drubbings – recall the scene with Whitworth, but he also verbally attacked the Austrian envoy in 1808, the Russian envoy in 1811 and a deputy from Hamburg in 1813 – as did monarchs. We saw what happened with Alexander in Erfurt in 1808. Some historians believe, echoing Napoleon’s own assertion, that these scenes were carefully prepared and were intended to strike fear into his opponents so that they would become compliant.

124

It is possible that he did so in a few instances, but on other occasions it is evident that the outburst was spontaneous, and violent.

Napoleon referred to these episodes as his ‘outbursts’ (the word in French is

transports

, which can also mean ‘rapture’). Essentially he was an egalitarian; he treated everybody the same; no one was exempt from his rage. He lacked the dignity, the courtesy and the serenity that was meant to characterize a monarch, and his behaviour is in sharp contrast to the way in which he was customarily depicted in paintings of the day – dignified and calm. Napoleon, however, was by no means the only eighteenth-century sovereign to behave appallingly. The King of Württemberg, Frederick I, was known for hitting his ministers and staff officers with a baton.

125

Alexander of Russia had a terrible temper and was capable of threatening and insulting with the best of them.

In the army, it was not uncommon for French officers, in pre-revolutionary times at least, to hit their men, either punching them, whipping them with their riding crops or hitting them with the flat of their swords (this was not limited to the French; corporal punishment in the Prussian army was notorious even by eighteenth-century standards). These were the times: physical abuse was common and a reasonably acceptable mode of behaviour. Power is often a question of force, something Napoleon used as an instrument of government, rather than refined manners. There is, however, the flipside to this coin – there are witnesses who insist that they never saw Napoleon lose his temper and that he was very attentive to others.

126

It shows the extent to which no historical evidence can be taken at face value.

15

‘For the Love of the Fatherland’

‘There can no longer be any question what Napoleon wants,’ Archduke Charles wrote to the Austrian Emperor, Francis. ‘He wants everything.’

1

Napoleon’s behaviour in Spain left the courts of Europe with the impression that his ambition knew no bounds. By that stage, Austria had already decided to go to war. The head of the war faction was the minister for foreign affairs, Johann-Philipp von Stadion. A professional diplomat who had served as ambassador at the courts of Berlin and St Petersburg, he had been in charge of foreign affairs since the end of 1805. Over the course of December 1808 and January 1809, he was able to convince the four important groupings at court – the military, the bureaucracy, the diplomatic corps and the imperial family – that it was in Austria’s best interests to resume war against France.

2

The war faction, encouraged by the difficulties the French were encountering in Spain, also comprised two of the Emperor’s own brothers – Grand Duke Ferdinand of Würzburg and Archduke John – as well as a number of other senior military and administrative figures, and the Emperor’s (third) wife, Maria Ludovica. Genuinely disturbed by the reports floating around Vienna of French atrocities in Spain, and inspired by the resistance of the Spanish people, Maria Ludovica began urging her husband to make a stand against Napoleon. Given that Francis was terribly in love with her, scholars generally agree that her influence over him was decisive.

3

Spain was an important factor, but the Austrian ambassador to Paris, the young, brilliant, if slightly delusional, and staunchly conservative aristocrat Klemens von Metternich, also had a part to play. His dispatches from Paris since the beginning of his mission in 1806 created a number of mistaken impressions: that war with France was inevitable; that Napoleon’s ultimate objective was the partition of the Habsburg monarchy; and that France was exhausted and tired of Napoleon’s ambitious projects.

4

Metternich reported that opposition to Napoleon was beginning to form at the highest political levels, and that the only people prepared to support another war were a small section of the army – that is, that Napoleon had lost the support of the French nation, whose greatest desire was peace.

5

As 1809 progressed, Metternich insisted that there could be no peace with a ‘revolutionary system’, and that Napoleon had declared ‘eternal war’ against the European powers.

6

Spain simply reinforced the view already held by Metternich, namely, that Napoleon was truly bent on universal domination. Talleyrand, who is reported to have told Metternich that Napoleon ‘hated [Austria] to death’, gave those views a little impetus.

7

Metternich had been a long-time advocate of conciliation with France, so his reports may have been that much more powerful.

When Stadion recalled Metternich to Vienna for political consultations between November 1808 and January 1809 (Napoleon was away in Spain), the ambassador spoke personally with the Austrian Emperor on a number of occasions, and later submitted three memoranda on the situation, urging that Austria take advantage of Napoleon’s absence in Spain to launch an attack against him.

8

Stadion, too, delivered a memorandum in which he reminded Francis that Napoleon had boasted in 1806 that he would make his dynasty the oldest in Europe.

9

It simply reinforced the notion that no monarchy was safe. It did not take much for Stadion to convince Francis that with the House of Bourbon now virtually eliminated from Europe, the Habsburgs were next on Napoleon’s hit list. The fact that Napoleon had made threatening noises against Austria the previous year while he was at Erfurt, openly suggesting that he was in a position to dismember the Austrian monarchy if he wanted to, only reinforced the perceived threat.

10

Appeasement was no longer possible under those conditions. At most, it would delay the inevitable destruction of the Habsburg monarchy. Even the Archduke Charles had to concur, and suggested that Austria start making preparations for a war, even though he did not hold out much hope of success.

11

Charles was right about Austria’s chances of success, and he ought to have known. He was considered one of the ablest generals of his time, and he had been placed in charge of reforming the Austrian army after the last resounding defeat in 1805. That was three years before, during which time a gigantic effort had been made to mobilize almost 450,000 men, and another 150,000 had been organized into a national militia known as the Landwehr,

12

while the army had been restructured with the formation of independent army corps and the reorganization of the field artillery. The last two reforms, however, were problematic since, introduced only at the beginning of 1809, they had not yet become firmly established. Corps commanders, for example, had little or no practical experience, unlike their French counterparts who were all battle hardened.

13

Charles had, in effect, attempted to transpose the French Revolution’s ‘nation in arms’ – the idea that the entire population was at the disposal of the country’s war machine – on to Austria, believing naively that when war broke out the people of Germany would rally behind the Austrian throne in much the same way that the Spanish people had rallied behind their monarchy. Vienna had been inspired by the Spanish example – reports about Spain regularly appeared in the

Wiener Zeitung

14

– but some in the Austrian political elite mistakenly believed they could somehow replicate the people’s uprising from the top. There was a concerted effort to mobilize public support for the war through newspapers, pamphlets, poems, sermons from church pulpits and official proclamations: Francis II appealed to all Austrian men to join either the army or the militia ‘for the love of the fatherland’.

15

Patriotic journals attempted to whip up support among the people, especially since many of those inspired in this way were conscripted for the first time. It was necessary to convince them that the war was meaningful, to instil particular ideas about the ‘fatherland’ and ‘national honour’, and to convince them that dying for the fatherland was the highest form of manly behaviour.

16

It was expecting too much. That kind of nationalist fervour was still in its incipient stages; Austria in 1809 was not France in 1792.

Eckmühl

Charles got off to a bad start.

17

The original plan was to march from Bohemia to the River Main in the hope of inspiring northern Germany to rise up, but then Charles changed his mind and ordered the army to concentrate in Bavaria. In doing so, he threw everyone and everything into disarray. Both supplies and troops had to be redirected, losing ten precious days in the process, and allowing the French time to concentrate their forces. Worse, once in Bavaria the Austrians proved lethargic and failed to crush the Bavarian army.

Napoleon, accompanied by Josephine this time, left Paris early in the morning of 13 April 1809. Seven hundred kilometres and four days later, they reached Donauwörth, about one hundred kilometres north-west of Munich. It was there that Napoleon learnt that the enemy was trying to break through at Regensburg (Ratisbon) further to the east. He therefore ordered his forces to concentrate at that town. Five days of fighting followed while Napoleon, complacent, unable to take seriously an army he had defeated many times before, tried to direct operations from a distance, without being fully apprised of the situation in a number of areas of operations. He was, therefore, basing his calculations on inaccurate information and on conjecture. It was not until 20 April when he arrived before Abensberg (not far from Regensburg) that he was able personally to direct operations. The battle that followed south of Regensburg at Eckmühl (or Eggmühl) on 22 April was indecisive and did no more than maul the main Austrian army.

18

There followed the storming of Regensburg during which Napoleon was wounded slightly in the heel (23 April). News of the incident quickly ran through the ranks, which is exactly why, despite the pain – ‘it hardly scratched the Achilles tendon’, he reassured Josephine – he immediately got back on his horse and rode among the ranks, bestowing decorations on soldiers he passed.

19

The upshot was that Napoleon failed to deliver a knockout blow and the Archduke Charles made good his escape across the Danube. The campaign was really only just beginning. Charles, however, was made so despondent by the mauling he had received at Eckmühl that he was already prepared to throw in the towel and advised his brother to make peace.

20

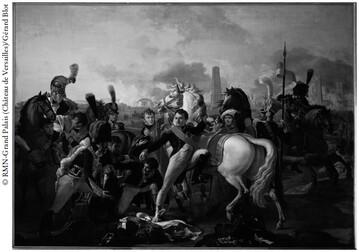

Pierre Gautherot,

Napoléon Ier, blessé au pied devant Ratisbonne, est soigné par le chirurgien Yvan, 23 avril 1809

(Napoleon I, wounded in the foot at Ratisbon, is treated by the surgeon Yvan, 23 April 1809), 1810. An idealized vision of Napoleon’s wounding. Gautherot was a student of David.