City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (38 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

Some of this wealth flowed north into the Syrian cities of

Damascus and Beirut. For most of it the destination was Cairo, from where goods were reloaded into flat-bottomed boats and floated down the Nile to Alexandria, the bridgehead with the infidel world. It was here, after the war of Chioggia, that Venice particularly concentrated its commercial efforts and proceeded to crush its rivals, not by warfare, but by patience, commercial acumen and superior organisation. In the century after the peace with Genoa in 1381, the Republic fine-tuned all the unique mechanisms of its mercantile system to dominate oriental trade. What came together was the potent combination of Venice’s unique collective endeavour, maritime evolution and the flowering of commercial and financial techniques.

Trading was hard-wired into the Venetian psyche; its heroes were merchants, the myths that it constructed for itself accentuated these values. Its historians conjured a past trading golden age, when ‘every man in Venice, both rich and poor, bettered his property … The sea was empty of robbers, and the Venetians brought goods to Venice, and merchants of all countries came to Venice and brought there merchandise of all kinds and took it back to their countries.’ Its iconic moments were framed in commercial terms – the same chronicler, Martino da Canal, cast Dandolo’s final rallying speech before the walls of Constantinople in 1204 in words that entwine religion and profits as conjoined values: ‘Be valiant, and with the help of Jesus Christ, my lord St Mark and the prowess of your bodies, you shall tomorrow be in possession of the city, and you shall be rich.’ The natural right to gain was the Venetian foundation myth.

By the Middle Ages, the mercantile republics of Italy had unshackled themselves from any lingering theological stigma attached to trade. Christ, rather than turning the money-changers out of the temple, could now be seen as a trader; piracy not usury was the Venetian idea of commercial sin. Profit was a virtue. ‘The entire people are merchants,’ observed a surprised visitor from feudal, land-holding Florence in 1346. Doges traded, so did artisans, women, servants, priests – anyone with a little cash in hand

could loan it on a merchant venture; the oarsmen and sailors who worked the ships carried small quantities of merchandise stashed beneath their benches to hawk in foreign ports. Only colonial officials during their periods of office were excluded. There was no merchant guild in the city – the city was a merchant guild, in which political and economic forces were seamlessly merged. The two thousand Venetian nobles whose senatorial decrees managed the state were its merchant princes. The city expressed a development in human behaviour that struck outsiders forcefully with the shock of modernity and not without alarm. The purity of the place was unmissable, as if it expressed an entirely new phenomenon; ‘It seems as if … human beings have concentrated there all the force of their trading,’ reported Pietro Casola. As the diarist Girolamo Priuli bluntly put it, ‘Money … is the chief component of The Republic.’

Venice was a joint-stock company in which everything was organised for fiscal ends. It legislated unwaveringly for the economic good of its populace, in a system that was continuously adjusted and tweaked. From the start of the fourteenth century it evolved a pattern of overseas trade, communally organised and strictly controlled by the state with the consistent aim of winning economic wars: ‘Nothing is better to increase and enrich the condition of our city than to give all liberty and occasion that commodities of our city be brought here and procured here rather than elsewhere, because this results in advantage both to the state and to private persons.’ It was through the application of sea power that it sought monopoly. A century of nautical revolution – the development of charts and compasses, novel steering systems and ship designs – had opened up new possibilities. From the 1300s ships were able to sail the short choppy seas of the Mediterranean in both summer and winter. A larger merchant galley was evolved, principally a sailing vessel with oars to manoeuvre in and out of ports and in adverse seas, which increased cargo sizes and cut journey times. A galley that could carry 150 tons below deck in the 1290s had enlarged to a carrier of 250 tons by the 1450s. This

galea grossa

was heavy on manpower. It required a crew typically of over two hundred, including 180 oarsmen who could also fight and twenty specialist crossbowmen as a defence against pirates, but it was comparatively fast, manoeuvrable and ideal for the safe transport of valuable cargoes. Alongside these were the cogs and carracks, high-sided sailing vessels manned by small crews, used mainly for transporting bulk supplies, such as wheat, timber, cotton and salt. It was the sailing ships that provided the staples to keep Venice alive; galleys coined the gold.

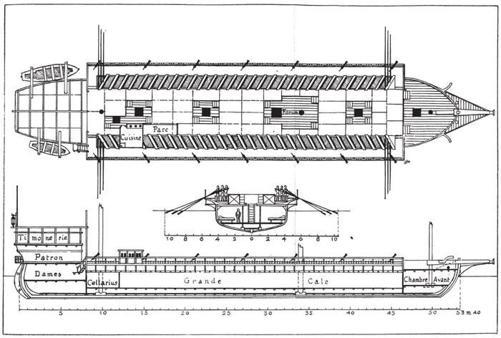

The merchant galley. Its central hold was adapted to form a dormitory on pilgrim voyages to the Holy Land

The merchant galleys, built in the arsenal, were property of the state, chartered out by auction each year to bidders. The aim was to manage entrepreneurial activity for the good of both people and state and prevent internecine competition of the sort that wrecked Genoa. Every detail of this system was strictly controlled. The

patrono

(organiser) of the winning syndicate had to be one of the two thousand nobles whose families were enrolled in the Golden Book, the register of the Venetian aristocracy, but the sailing captain was a paid employee of the state, responsible for the ship’s safe

return. Crew sizes and rates of pay, weapons to be carried, freight rates to be paid, goods to be transported, ports of call to be visited, sailing times, destinations and stopover periods were all stipulated. Maritime legislation was heavy and precise, as were the penalties for abuse. The galleys travelled set routes, like a timetabled service, the details of which, set down in the early 1300s, were to last for two hundred years. At the end of the fourteenth century there were four: those to Alexandria, Beirut, Constantinople and the Black Sea, and the long-range Atlantic haul, an arduous five-month round trip to London and Bruges. A century later this had expanded to seven, visiting all the major ports of the Mediterranean. After 1418 Venice also cornered the pilgrim market. Two galleys a year would depart for Jaffa carrying profitable shiploads of pious tourists to wonder at the sights of the Holy Land. In the fifteenth century Venetian galleys quartered the seas with high-value goods while cogs carried the bulk merchandise.

Venice’s genius was to grasp the laws of supply and demand, based on centuries of mercantile activity, and to obey them with unmatched efficiency. The secret lay in regularity. Venetian merchants lived with an acute sense of time. The clocks in St Mark’s Square and in the Rialto fixed the pattern of the working day. On a larger scale the annual pattern of voyaging was dictated by seasonal rhythms far beyond the confines of Europe. The metronomic cycle of monsoon winds over the Indian subcontinent set in motion a series of interconnecting trading cycles, like the meshing cogs in an enormous mechanism, which moved goods and gold all the way from China to the North Sea. Borne west on the autumn winds in the wake of the monsoon (the Arabic

mawsim

, a season), ships from India departed for the Arabian peninsula in September, carrying spices and the goods of the Orient. These would be trans-shipped to reach Alexandria and the marts of Syria in October. The Venetians’ merchant convoys would depart for Alexandria in late August or early September, within a time slot rigorously dictated by the senate, reaching their destination a month later to coincide with the arrival of these

goods. Beirut was set to the same rhythm. The duration of the stays was firmly fixed – Beirut usually twenty-eight days, Alexandria twenty – and enforced with severity. Return was set for mid-December, variable within a month for the hazards of winter navigation. With the snow on the mountains the great galleys would haul themselves back into Venice to mesh with another set of trading rhythms. German merchants, furred and booted, would jingle their way across the Brenner Pass from Ulm and Nuremberg with pack animals for the winter fair. The departure and arrival of the long-distance Flanders galleys would also be synchronised to interlock with this exchange and with the sturgeon season and the silk caravans at Tana.

What Venice had understood was the need for predictable delivery, so that foreign merchants drawn there could be confident that there would be desirable merchandise, worth the long haul over the Brenner Pass in the grip of winter. Venice made itself the destination of choice, profiting individually by the trades and as a state from the element of tax it extracted from the movement of all goods in and out. ‘Our galleys must not lose time’ was the axiom.

It was never a perfect system. There could be delays in the arsenal fitting out the vessels for departure, contrary winds, menacing pirates and political turmoil in any of the countries to which the galleys went to trade. The round trips had a reasonable predictability: three months to Beirut, five to Bruges. In exceptional circumstances, however, the time lags were immense. The shortest round trip on the Tana route was 131 days, the longest 284; in 1429 the Flanders galleys sailing on 8 March overwintered and did not tip the lagoon again until 25 February the following year. In cases of late return, the goods were almost always sequestered, so that when merchants arrived at Venice for the regular trade fairs they could be certain of a healthy stock of merchandise to buy. Customer satisfaction was the key.

Each route conformed to its own rhythm, and the Venetians conferred on these cyclical convoys the name of

muda

, a word

which conveyed a complex set of meanings. The

muda

was both the season for buying and exchanging spices, and the merchant convoy that carried them. The various different

mude

played an emotional part in the annual round of the city’s life. The city stirred into intense activity in the run-up to sailings. The arsenal worked overtime through the hot summer days ready for the Levant sailing; as the departure approached there would be a hubbub along the waterfront. Benches were set up for recruiting crews; merchandise and food, oars and sailing tackle were sorted, parcelled up and ferried out to the galleys anchored off shore. The voyage was blessed in St Mark’s or the seafarers’ church of St Nicholas on the Lido and the ships set sail watched by an intent crowd, for some of whom the enterprise contained their ready wealth. When the German pilgrim Felix Fabri left on a pilgrim galley in 1498 it was ceremonially decked out with banners;

… after the galley was dressed they began to get ready to start, because we had a fair wind, which was blowing the banners up high. The crew began with a loud noise to weigh up the anchors and take them on board, to hoist the yard aloft with the mainsail furled upon it, and to hoist up the galley’s boats out of the sea; all of which was done with exceeding hard toil and loud shouts, till at last the galley was loosed from her moorings, the sails spread and filled with wind, and with great rejoicing we sailed away from the land: for the trumpeters blew their trumpets just as though we were about to join battle, the galley-slaves shouted, and all the pilgrims sang together ‘We go in God’s name’ … the ship was driven along so fast by the strength of a fair wind, that within the space of three hours we … had only the sky and the waters before our eyes.

The ritual of departure, the crossing of the threshold of the lagoon to the open sea, were pivotal moments in the communal experience of Venetian people, as well as for outsiders. There was both excitement and apprehension. Wills were written. Some on board would not return.

The merchant galleys regularly carried a handful of young noblemen, recruited as crossbowmen, as apprentices learning the

skills of trade and the seafaring life. For many of these ‘nobles of the poop’ this was their first overseas experience. When Andrea Sanudo was preparing for his first voyage to Alexandria in the late fifteenth century, his brother Benedetto gave him copious instructions on how to behave and what to expect and avoid. They ranged widely from behaviour on board ship – treat the captain with reverence, only play backgammon with the chaplain, how to cope with seasickness – to the perils of port life – avoid the prostitutes of Candia: ‘they are infected with the French disease’ – and eating quails in Alexandria.

There was much to learn, both cultural and commercial, about foreign parts. Andrea was advised to shadow the local Venetian agent: ‘Always stay with him, learning to recognise every sort of spice and drug which will be of enormous benefit to you.’ Information was as vital as cash to all merchants voyaging to lands where dealings might be conducted through an interpreter in unfamiliar weights, measures and currencies. Practical handbooks were compiled with trading information on all the concerns of the travelling merchants, and these were widely circulated. Local currency conversions, units of measure, the quality of spices, how to avoid fraud were all covered. One of these, the

Zibaldone da Canal

, reveals the difficulties of conducting dealings on a foreign shore. In Tunis, it helpfully explains,