City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (40 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

But the diplomacy worked. Self-discipline, straight dealing and an appeal to reason over armed force won the grudging respect of the Cairo court – and a sideways glance from much of Christendom, as the Mamluks’ friends. Decade by decade through the fifteenth century they inched ahead of their rivals. The regularity of their galley lines made the wheels of commerce turn. The

muda

’s arrival at Alexandria was as welcome to the Egyptians as was its return to the Germans. By 1417 Venice was the foremost trading nation in the eastern Mediterranean; by the end of the century they had crushed the competition. In 1487 there were only three

fondaci

left in Alexandria, the two Venetian and one Genoese; the other nations had withdrawn from the game. Venice beat Genoa, not so much at Chioggia, but in the long-drawn-out, unspectacular trade wars of the Levant. And the profits were huge: up to eighty per cent on cotton, sixty per cent on spices, when sold on to foreign merchants on the Rialto.

The winter spice fleets returning from the Levant, whose imminent arrival would be heralded by fast cutters, would be seen first from lookouts on the campanile of St Mark and welcomed home by the thunderous peal of church bells. The arrivals of the various

mude

– cotton cogs from Beirut, merchant galleys from Languedoc, Bruges, Alexandria or the Black Sea – slotted between the round of religious processions, feast days and historical remembrances, were great events in the cycle of the year. The Alexandria

muda

, putting in some time between 15 December and

15 February, sparked off an intense period of commercial activity. Swarms of small boats put out to welcome the galleys home; everything had to be landed at the maritime customs house – the

dogana da mar

– on the point jutting out into the Basin of St Mark. The word

dogana

(divan) was an exotic Arabic import like the goods it contained. No bales could be landed until they had paid the import tax (between three and five per cent) and been stamped with its seal – though abuses were numerous.

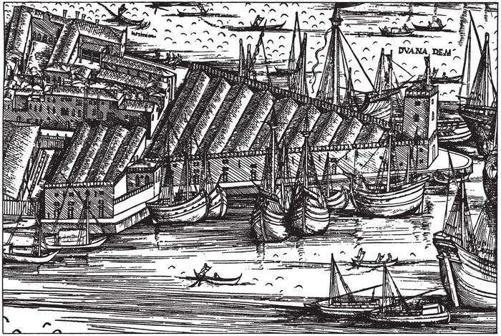

The maritime customs house

Throughout all the centuries of port life, the Basin of St Mark was a chaotic, colourful theatre of maritime activity. The Venetians treated it as an industrial machine, outsiders were just amazed. The landscape of spars and masts, rigging and oars, barrels and bales dumped on quaysides, the hubbub of ships and merchandise, was celebrated in the great panoramas of Venetian painting, from fifteenth-century woodcuts jammed with detail to the bright seascapes of Canaletto in the eighteenth. Venice was a world of ships. The literal-minded Canon Casola tried to count them, starting with gondolas, but gave up, having already excluded from his count ‘the galleys and

navi

for navigating long distances because

they are numberless … There is no city equal to Venice as regards the number of ships and the grandeur of the port.’

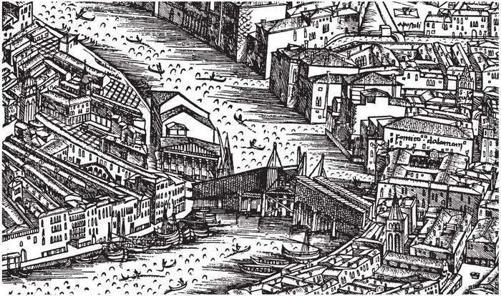

Once taxed and cleared through customs, goods were loaded onto lighters, ferried up the Grand Canal and landed at the Rialto or unloaded into barred ground-floor warehouses, via the water gates of the palaces of the merchant princes. It was the Rialto, situated at the mid-point of the wide S-bend of the Grand Canal, that comprised the centre of the whole commercial system. Its wooden bridge was the only crossing point in the fifteenth century. Here was Venice’s second customs house – the

dogana da terra

– where all the goods floated down the rivers of Italy or packhorsed across the Alpine passes arrived by barge. This meeting point became the axis and turntable of world trade. It was, as the diarist Marino Sanudo put it, ‘the richest place on earth’.

The abundance dazzled and confounded. It seemed as if everything that the world might contain was unloaded here, bought and sold, or repackaged and re-embarked for sale somewhere else. The Rialto, like a distorted reflection of Aleppo, Damascus or medieval Baghdad, was the souk of the world. There were quays for unloading bulk items: oil, coal, wine, iron; warehouses for flour and timber; bales and barrels and sacks that seemed to contain everything – carpets, silk, ginger, frankincense, furs, fruit, cotton, pepper, glass, fish, flowers – and all the human activity that animated the quarter; the water jammed with lighters and gondolas, the quays thronged by boatmen, merchants, spice garblers (examiners), porters, customs officials, foreign merchants, thieves, pickpockets, prostitutes and pilgrims; on the quaysides a casual spectacle of chaotic unloading, shouting, hefting and petty theft.

This was the bazaar of Europe and the historic location of Venice’s founding myth. It was held that Venice was established here on Friday 25 March 421, at noon precisely, by the site of the Church of San Giacomo di Rialto, the merchants’ church, said to have been built the same year. An inscription on its walls sternly enjoined probity and fair dealing: ‘Around this temple let the merchant’s law be just, his weights true and his promises faithful.’ The

square beside the church was the centre of international commerce, ‘where all the business of the city – or rather, of the world – was transacted’. Here the proclamations of the state were read out and the bankers, seated at long tables, entered deposits and payments in their ledgers, and transferred by bills of exchange considerable sums from one client to another without the least movement of actual cash; here the public debt was quoted and the daily price of spices compiled, set forth in lists and distributed to the many merchants – both resident and foreign. Unlike the bawl of the retail markets, everything was conducted demurely in a low voice, as befitted the honour of Venice: ‘no voice, no noise … no discussion … no insults … no disputes’. In the loggia opposite, they had a painted map of the world, as if to confirm that all its trade might be imagined here and a clock that ‘shows all the moments of time to all the different nations of the world who assemble with their goods in the famous piazza of Rialto’. The Rialto was the centre of international trade: to be banned from it was to be excluded from commercial life.

The Rialto to the left of its wooden bridge. The German

fondaco

is the named building on the right.

From this epicentre radiated all the trades, activities and exchanges that made Venice the mart of the world. On the Rialto Bridge were displayed news of

muda

sailings and the announcement of galley auctions, which were conducted by an auctioneer standing on a bench and timed by the burning of a candle. Across the canal the Republic lodged its German merchants in their own

fondaco

, and managed them almost as carefully as they themselves were by the Mamluks; around lay the streets of specialist activities – marine insurance, goldsmithing, jewellery. It was the sheer exuberance of physical stuff, the evidence of plenty that overwhelmed visitors such as the pilgrim Pietro Casola. He found the area around the Rialto Bridge ‘inestimable … It seems as if all the world flocks there.’ Casola tried to see it all, rushing from site to site, stunned by the quantities, the colours, the size, the variety, and recording his impressions in dizzying and ever expanding superlatives:

… what is sold elsewhere by the pound and the ounce is sold there by the

canthari

and sacks of a

moggio

each … so many cloths of every make – tapestry, brocades and hangings of every design, carpets of every sort, camlets of every colour and texture, silks of every kind; and so many warehouses full of spices, groceries and drugs, and so much beautiful white wax! These things stupefy the beholder, and cannot be fully described to those who have not seen them.

The sensuous exuberance of the Rialto hit outsiders like a physical shock.

From here Venice controlled an axis of exchange that ran from the Rhine valley to the Levant and influenced trade from Sweden to China, funnelling goods across the world system: Indian pepper to England and Flanders, Cotswold wool and Russian furs to the Mamluks of Cairo; Syrian cotton to the burghers of Germany; Chinese silk to the mistresses of Medici bankers, Cyprus sugar for their food; Murano glass for the mosque lamps of Aleppo; Slovakian copper; paper, tin and dried fish. In Venice there was a trade for everything, even ground-up mummies from the Valley of the Kings, sold as medicinal cures. Everything

spun off the turntable of the Rialto and was despatched again by the

muda

to another port or across the lagoon, up the rivers and roads of central Europe. And on every import and export the Republic levied its share of tax. ‘Here wealth flows like water in a fountain,’ wrote Casola. All it actually lacked was passable drinking water. ‘Although the people are placed in the water up to the mouth they often suffer from thirst.’

In the 1360s Petrarch had marvelled at the ability of the Venetians to exchange goods across the vast expanses of the world. ‘Our wines sparkle in the cups of the Britons,’ he wrote, ‘our honey is carried to delight the taste of the Russians. And hard though it is to believe, the timber from our forests is carried to the Egyptians and Greeks. From here, oil, linen and saffron reach Syria, Armenia, Arabia and Persia in our ships, and in return various goods come back.’ The great man had grasped the genius of Venetian trade, even if he was poetically hazy about the details. (The honey was coming from Russia.) A century later, this process had reached its fruition. Its merchants were everywhere – buying, selling, bargaining, negotiating, avid for profit, single-minded and ruthless, exploiting whatever opportunities existed for coining gold. They had even cornered the market in holy relics. The theft of bones – dubious yellowing skulls, hands, whole corpses or dissected pieces (forearms, feet, fingers, locks of hair) – along with material objects attached to the life of Christ added respect to the city and enhanced its potential for the lucrative tourist pilgrim trade. St Mark in 828 was followed by a long list of looted body parts, many of which were acquired during the Fourth Crusade, and which made Venice a stopover of particular attraction for the pious. (So plentiful was this collection of human fragments that the Venetians became hazy about what they had: the head of St George was retrieved from a cupboard in the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore by the American scholar Kenneth Setton in 1971.)

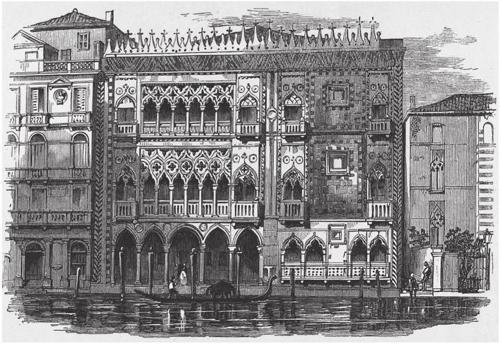

The Ca’ d’Oro

The visual city had become a place of wonder. To float down the Grand Canal past the great palazzos of the merchant princes,

such as the Ca’ d’Oro shimmering in the sun with its covering of gold leaf, was to be exposed to an astonishing drama of activity, colour and light. ‘I saw four-hundred-ton vessels pass close by the houses that border a canal which I hold to be the most beautiful street,’ wrote the Frenchman Philippe de Commynes. To attend mass in St Mark’s or witness one of the great ceremonial rituals that punctuated the Venetian year – the Senza or the inauguration of a doge, the appointment of a captain-general of the sea, the blaring of trumpets, the waving of red-and-gold banners, the parading of prisoners and captured war trophies; to witness the guilds, clergy and all the appointed bodies of the Venetian Republic in solemn procession around St Mark’s Square – such theatrical displays seemed like the manifestations of a state that was uniquely blessed. ‘I have never seen a city so triumphant,’ declared Commynes. It all rested on money.