City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (18 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

*

In the immediate aftermath, Constantinople witnessed a lewd and grotesque carnival. ‘The beef-eating Latins’, as Choniates dubbed them, roamed through the streets, ‘riotous and indecent’, mimicking the dress and customs of the Byzantines. They

dressed themselves in Greek robes, ‘to mock us and placed women’s headdresses on their horses’ heads, and tied the white bands which hang down their backs round their beasts’ muzzles’, and planted the distinctive Greek hats on their horses’ heads and rode through the streets with abducted women on their saddles. Others, ‘holding scribes’ reed pens and inkwells, mimicked writing in books, mocking us as secretaries’. To Choniates’s refined palate, these men were barbarians, guzzling and carousing all day long, gorging themselves on delicacies and their own disgusting, crude, pungent food – ‘the chines of oxen boiled in cauldrons, chunks of pig mixed with bean paste and cooked up with a marinade of garlic paste and foul-smelling garlic’.

To this debauchery would be added the wholesale destruction of a thousand years of imperial and religious art. In the aftermath, the conquerors, with their hunger for precious metals and the copper and bronze from which to mint coins, cast into the furnace an extraordinary catalogue of statuary, much of which was ancient even at the city’s founding in the fourth century, collected from across the Roman and Greek world by Constantine the Great. To Choniates the destruction was endless, ‘like a line stretching out to infinity’. Under the blows of hammers and axes they felled the giant bronze figure of Hera, so immense that it took four oxen to cart the head away, and an enormous equestrian statue from its plinth in the Forum of the Bull, carrying a rider who ‘extended his right hand in the direction of the chariot-driving sun … and held a bronze globe in the palm of his hand’. All these were melted down for coins.

The Venetian role in this rape and pillage goes largely unrecorded, though one German chronicler, keen perhaps to point a finger elsewhere, declared that the Italian merchants expelled from the city, particularly the Venetians, were responsible for the slaughter in a spirit of revenge. Choniates, who loathed Dandolo as a sly cheat largely responsible for the catastrophe, picked out the French crusaders as the most muscular pillagers of his beloved city – and owed the safety of himself and

his family to the courage of a Venetian merchant. The Venetians at least had perhaps a more discerning attitude to the works of art that they plundered.

All the parties had solemnly sworn that the booty would be centrally collected and equitably divided according to clearly agreed rules. Baldwin of Flanders wrote that ‘an innumerable amount of horses, gold, silver, costly tapestries, gems and all those things that people judge to be rich is plundered’. Much was never handed in; the poor, according to Robert of Clari, were again cheated. But the Venetians received the 150,000 marks owed to them under the terms of the agreements, and another hundred thousand to share amongst themselves. In material terms Dandolo’s gamble seems to have paid off.

When it came to appointing a new emperor, Dandolo, in his nineties, excused himself from consideration, judging that, apart from his age, the election of a Venetian would be enormously contentious. There were two rival candidates, the counts Baldwin and Boniface. The Venetians probably threw their weight behind Baldwin, judging his rival too closely tied to Genoa. Venice’s prime concern was above all to secure stability for its trading interests in the eastern Mediterranean, but the Latin Empire of Constantinople, as it came to be known, was shaky from the first; it was beset by internal squabbles between the feudal lords and outside pressure from the Byzantines and the neighbouring Bulgarians. For most of the surviving protagonists it would end badly. Murtzuphlus, who had escaped from the city, was treacherously blinded in exile by the other exiled rival, Alexius III; recaptured by the crusaders, he was prepared for a special end, reputedly devised by Dandolo. ‘For a high man, I will detail the high justice one should give him!’ He was taken to the base of the tall column of Theodosius, prodded up the internal steps to the platform at the top; sightless, but grasping his imminent fate, and watched by an expectant crowd, he was pushed off. Baldwin, the first emperor of the Latin Kingdom of Constantinople, died slowly in a Bulgarian ravine, his arms and legs chopped off at the

joints; his rival, Boniface, also killed in a Bulgarian ambush, had his skull despatched to the Bulgarian tsar as a gift.

The blind doge survived, shrewd to the last. With a cool head, he masterminded a successful withdrawal of a crusader army almost encircled by the Bulgarians in the spring of 1205. Everyone who came in contact with the old man recognised his unique powers of discrimination and prudence. His superior judgement had saved the crusade from repeated disaster. He was, according to Villehardouin, ‘very wise and worthy and full of vigour’ to the end. Even Pope Innocent paid a kind of backhanded tribute to a man whom he heartily loathed. The Venetians had committed to stay at Constantinople until March 1205. A resident population remained to occupy their share of the city, but with the year up many more prepared to sail home. Dandolo, knowing that the end of his life was near, applied to the pope for release from his crusader vows and to be allowed to return too. Innocent had the last laugh – insisting that the aged old doge should proceed with the army to the Holy Land, to which it would never now go. ‘We are mindful’, he began smoothly,

that your honest circumspection, the acuteness of your lively innate character, and the maturity of your quite sound advice would be beneficial to the Christian army far into the future. Inasmuch as the aforesaid emperor and the crusaders ardently praise your zeal and solicitude and among [all] people, they trust particularly in your discretion, we have not considered approving this petition for the present time, lest we be blamed … if, having now avenged the injury done to you, you do not avenge the dishonour done Jesus Christ.

It must have afforded Innocent some impious satisfaction to gain the advantage, though he finally lifted the sentence of excommunication on the old man in January 1205. Dandolo spent his last days a long way from the lagoon. Like his father before him, he died in Constantinople. In May 1205 he breathed his last and was buried in Hagia Sophia, where his bones would remain for 250 years, until another convulsion racked the imperial city.

Innocent had initially applauded the deeds of the crusaders in bringing the Byzantines under the Catholic Church. Dandolo had been dead for two months before the truth about the city’s fall finally reached him. His verdict fell on the crusaders like a scourge. Their enterprise had been ‘nothing but an example of affliction and the works of hell’. The sack of Constantinople burned a hole in Christian history; it was the scandal of the age and Venice was held to be deeply complicit in the act. It would reinforce papal views of the merchant crusaders, who traded unapologetically with Islam, as enemies of Christ. The label would be regularly reapplied down the centuries. But for Venice it was an extraordinary and unlooked-for opportunity. They had set out in the autumn of 1203, banners flying, to conquer Egypt. The fortunes of the sea had carried them away to unforeseen destinations. As for their actual part in the proceedings they kept silent. There are no contemporary Venetian accounts of the crusade that was intended to take Jerusalem via Cairo but ended up in Christian Constantinople.

*

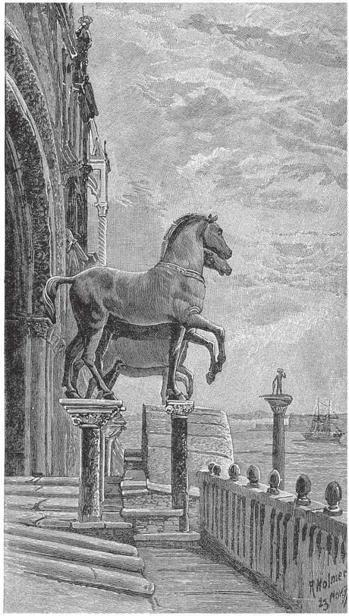

On 1 October 1204, the Byzantine Empire was formally divided among the victorious parties. The merchant crusaders returned from Constantinople with a rich array of trophies, marbles and holy relics. Where the Frankish crusaders hacked up and melted down, the Venetians picked their plunder like connoisseurs, carrying back to the lagoon intact works of art to beautify and ennoble the city. Along with the bodies of saints – Lucia, Agatha, Simeon, Anastasius, Paul the Martyr – they acquired caskets, icons and jewelled treasures, statues, marble columns and sculptured reliefs. Much of this went to adorn St Mark’s; a pair of ancient bronze doors was installed at its entrance; a Roman statue was used to form the body of St Theodore with his crocodile atop one of the twin columns nearby; Dandolo himself was said to have selected from the Hippodrome the four bronze-gilt horses caught in dramatic and frozen motion with nostrils flaring and hooves raised, which came, along with the lion of Venice, to define the Republic’s sense of itself: proud, imperial – and free. Dandolo had ensured that the Venetians, alone of all the participants in the Fourth Crusade, did not pay homage to its new emperor; they kept themselves clear of the whole edifice of feudal obligation.

The spoils of war

Along with their exquisite spoils of war, winched ashore on the quays of Venice after the sack of 1204, the city acquired something else. Overnight it had gained an empire. Of all the parties that had set out in the autumn of 1202, it was the Republic that had profited most handsomely. Dandolo had taken the opportunity and shaped, for the lagoon dwellers, an extraordinary advantage.

PART II

ASCENT: PRINCES OF THE SEA

1204–1500

A Quarter and Half a Quarter

1204–1250

By the partition of Byzantium in October 1204, Venice became overnight the inheritor of a maritime empire. At a stroke, the city was changed from a merchant state into a colonial power, whose writ would run from the top of the Adriatic to the Black Sea, across the Aegean and the seas of Crete. In the process its self-descriptions would ascend from the Commune, the shared creation of its domestic lagoon, to the Signoria, the Serenissima, the Dominante – the dominant one – a sovereign state whose power would be felt, in its own proud formulation, ‘wherever water runs’.

On paper the Venetians were granted all of western Greece, Corfu and the Ionian islands, a scattering of bases and islands in the Aegean Sea, critical control of Gallipoli and the Dardanelles, and most precious of all, three eighths of Constantinople, including its docks and arsenal, the cornerstone of their mercantile wealth. The Venetians had come to the negotiating table with an unrivalled knowledge of the eastern Mediterranean. They had been trading in the Byzantine Empire for hundreds of years and they knew exactly what they wanted. While the feudal lords of France and Italy went to construct petty fiefdoms on the poor soil of continental Greece, the Venetians demanded ports, trading stations and naval bases with strategic control of seaways. None of these were more than a few miles from the sea. Wealth lay not in exploiting an impoverished Greek peasantry, but in the control of sea lanes along which the merchandise of the east could be channelled into the warehouses of the Grand Canal. Venice came in time to call its overseas empire the Stato da Mar, the territory of the sea. With two exceptions it never comprised the occupation

of substantial blocks of land – the population of Venice was far too small for that – rather it was a loose network of ports and bases, similar in structure to the way stations of the British Empire. Venice created its own Gibraltars, Maltas and Adens, and like the British Empire it depended on sea power to hold these possessions together.